BY STEPHANIE SPIRO

Luna Luna Magazine is putting together a special project about selfies, called #SELFIEWITCH (click here to participate). This got me thinking about the psychology of the selfie. A selfie may go beyond a documentation of a moment in time, a feeling that passes. Perhaps ‘selfie’ is not just a noun, but a verb? The act of selfie-taking can be an active stab at freedom, a snap to regain control as the storyteller and manipulator of our own lives.

To ‘selfie’ is to gaze back at anything oppressive. A selfie can be a purposeful, artful trick of perception, a stylized narrative that we create. We post our best or most expressive images after multiple attempts, filtered and framed and cut. The gaze that defines us pushes us into a corner, and the selfie pushes back, gazes back.

A few years ago, a bicycle hit me in Brooklyn. In just a split second, I lost all control of my narrative. When I opened my eyes, twelve people were around me, including a pair of tourists snapping photos. I turned to face the corner school where thirty kids lined up along the fence surrounding the playground silently watching me. I wrapped my body burrito-style in my sweatshirt and clutched my elbow. My arm was shattered. My head was bleeding and my eye was already turning black.

Two fire trucks and an ambulance pulled up and approached, referring to me as Quasimodo. A paramedic slid her hand over my arm and informed me that it was chipped. The fragment floating inside was my olecranon--a loose piece of elbow suspended in a grapefruit-sized ball of inflamed arm tissue.

The X-rayed crook of my arm looked a lot like an open can. The arm was there, and the elbow was resting on its tip, perpendicular to the arm, like a ballerina en pointe, twirling precariously to unheard music. The pieces connecting the elbow were pulverized and the elbow was chipped open and choreographed by fate into a frozen pirouette, bone fragments dancing over an obliterated arm.

After surgery, I was homebound, sad, and alone. I felt like a victim. So I started taking selfies even though I felt far from glamorous with a black eye and only one good arm, fumbling to attach my rotating collection of Robocop arm braces and casts. My solution? Make it a game and myself the hero of my own healing. I created little selfie albums on Facebook and told my story, my way. I called myself the Bionic Avenger. The selfies helped me make sense of a random accident as I built a new narrative around being a survivor, one selfie at a time. Thank you, smartphone. Thank you, Facebook. A selfie can be a form of healing.

Last week I binged on Marvel’s Jessica Jones on Netflix. Since then, I’ve read a barrage of the most amazingly insightful articles that focus on the anti-hero aspect of the show, and the show’s complex and incredible treatment of rape, trauma, PTSD, abortion, etc. In this post, I’ll focus primarily on the selfie-aspect, and I’ll pair the show with another show and a great, complementary silent film.

Subverting the Seflie

In the Marvel Universe, Jessica Jones is a superhero until she crosses paths with super villain Kilgrave, a man with terrifying powers of mind control. During their brief “courtship,” Kilgrave compels Jessica to be his girlfriend and his weapon. He forces her to smile and enjoy it until she manages to break away. Bundled like Anna Karenina, “just Jessica Jones” walks off into the moonlit streets of another genre to become a moto-clad noir detective.

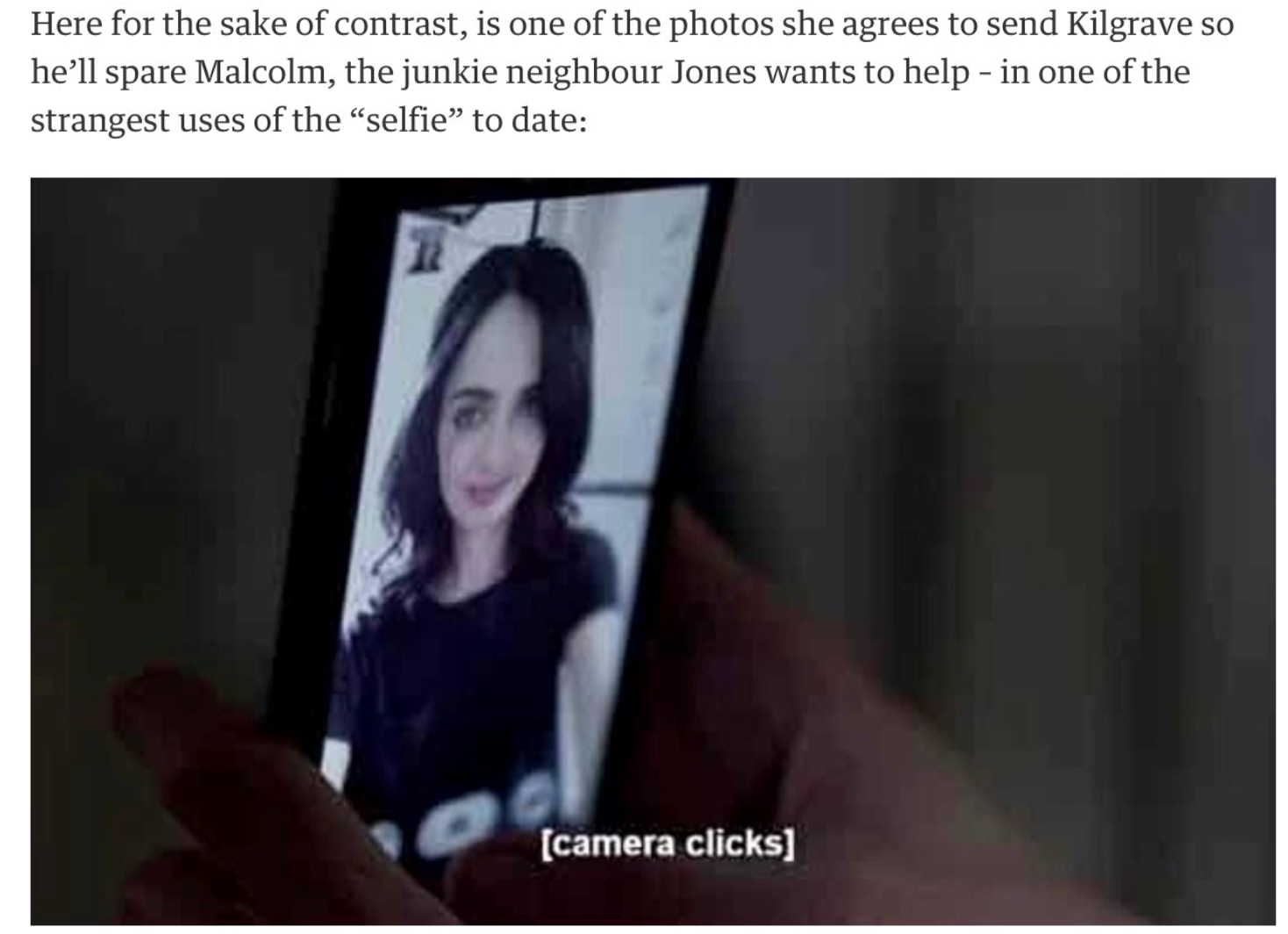

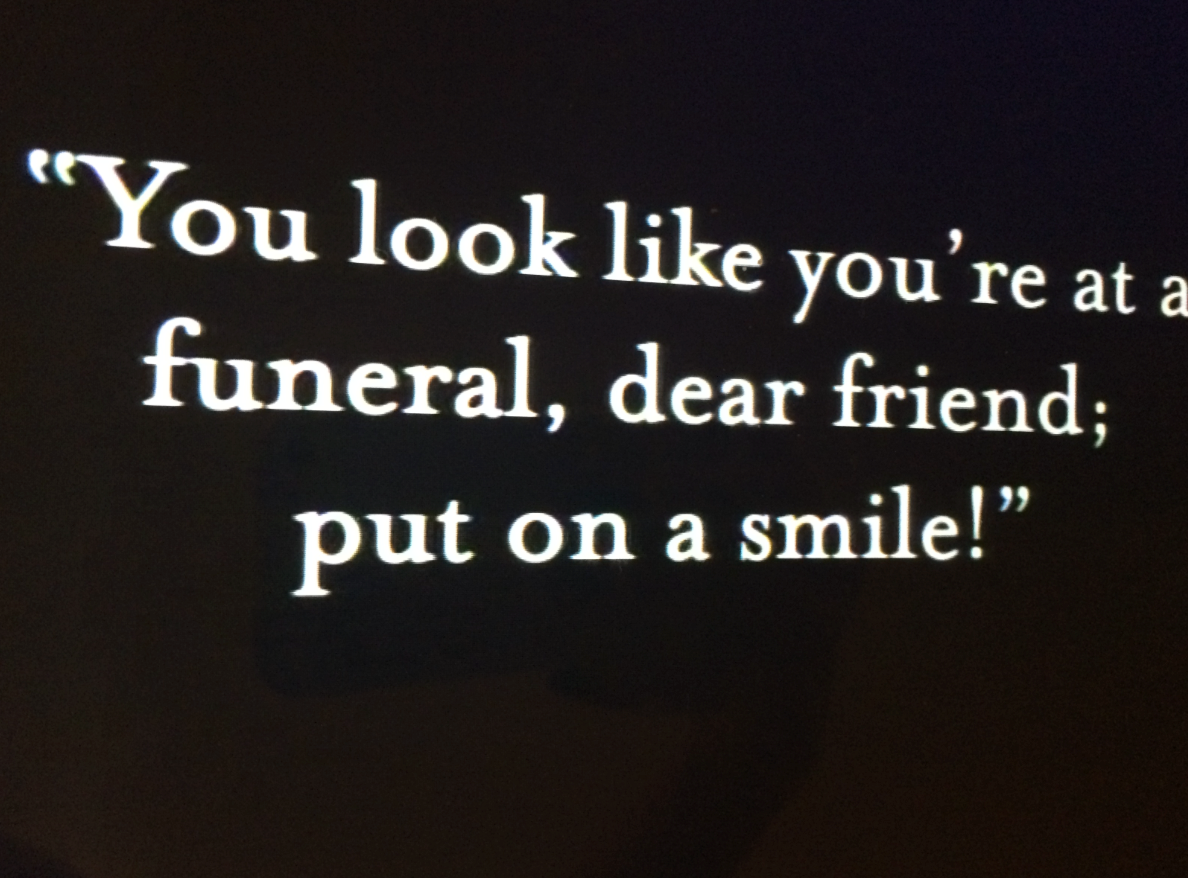

This respite is short-lived and Kilgrave wriggles his way back into Jessica’s life and threatens to hurt her friends if she doesn’t send him a selfie every day at 10am. Kilgrave has subverted and exploited a major tool of self-expression (the selfie). In doing so, he hijacks the narrative of Jessica’s identity just like he jacked in to her brain and eventually hijacks the narrative of the show (it’s very meta). The Guardian posted this photo:

The show’s poster even looks like a threatened selfie, Jessica’s darkened features fill the frame. The gaze is blank. Kilgrave looms ominously behind her:

The Complexity of Hope

Another major character in the Jessica Jones TV show is Hope, Kilgrave’s kidnap victim and forced “girlfriend” after Jessica. She is the second part of Jessica’s hijacked narrative: if Kilgrave’s oppressive selfie demands are the identity hijack, then Hope is the physical storyline hijack. When Hope’s parents visit Jessica’s detective agency for help retrieving their daughter, they kick off the story’s inciting incident, and Jessica loses all agency; she’s locked inside the chase until episode 13.

I looked up the word ‘hope’ in the online etymology dictionary and this is what I found:

“Old English ‘hopian,’ hope for salvation and mercy […] hold to hope in the absence of any justification for hope […] there may be a connection with ‘hop’ or the notion of leaping in expectation.”

Jessica’s driving force is Hope. She needs to help “Hope” because Hope is another woman compelled to suffer the same abuse and trauma that she suffered. Jessica needs to keep hope alive. It seems deliberate that a character named Hope would function as a plot device to keep Jessica moving swiftly forward. Hope is the only person who can end this story strain (season-long story arc). She is the only one who can set Jessica free and release her from an imposing narrative. Hope fuels the chase. As long as Hope is suffering, Jessica isn’t free.

“Alias & Mars Investigations: Healing the Hardboiled Way.”

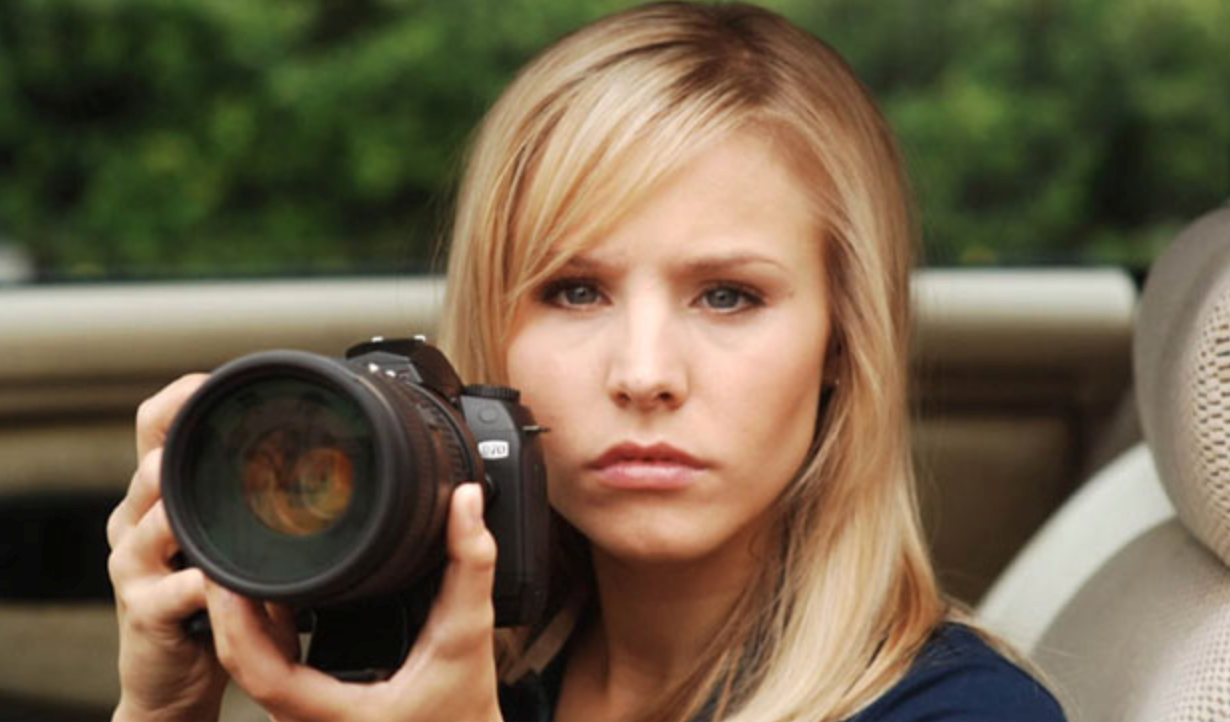

I see interesting similarities in the excellent TV show, Veronica Mars (2004-2007). In the Jessica Jones comic, Jessica is formerly the hero “Jewel,” a glittering object of desire without anything other than faint backstory and a kinky alias. She gives up the sheen and the cape, after a tragic and traumatic stint with Kilgrave. She forms the Alias Detective Agency.

Veronica Mars is also a rape victim, and the storyline picks up a few months after her rape. Veronica is coping with trauma under the alias of hard-boiled detective at Mars Investigations, pulling her gaze to the dominant side of the lens. She’s dominating her tale and slinking around in the night, capturing other peoples’ private moments. Veronica’s “selfie” action is her voiceover. It keeps her firmly rooted in herself. A clever and expressive voiceover becomes her inner armor.

Is it fishy that both female sleuths (Jessica Jones and Veronica Mars) become detective anti-heroes after a rape? I wonder…

In both shows recovery is in part about a trauma victim regaining the control of her narrative (quite literally, in JJ). To overcome the power of the gaze is to become the gaze (a detective is an outsider, secretly slipping inside other peoples’ narratives, recording them, controlling them, in a sense). The most intense image from Jessica Jones is the one used by Netflix to advertise: Jessica sits on a desk, legs folded, eyes penetrating the screen, gazing directly at us with a challenging laser focus, like she might pounce or shoot lasers from her eye sockets. Jessica’s lack of laser eye power is a running joke in the show and I believe this is relevant because it seems like a reference to Jessica’s season long stab at controlling the oppressive male gaze, to stare down the men and take back the power.

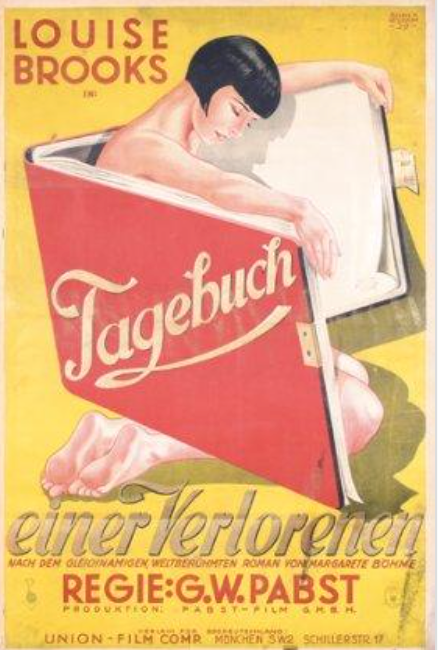

Diary of a Lost Girl (1929): A Selfie Relic

After you’ve binged on Jones, travel back in time to catch Louise Brooks in the incredible, Diary of a Lost Girl on Amazon Prime. The film starts with the Brooks character (Thymian) getting seduced and raped, having the child, losing the child. She is shipped off to a home for “wayward women” and subjected to every kind of abuse.

A particularly scary gentleman at the home grabs Brooks behind the neck when she tries to gaze out the window. It’s a gesture of control, almost like mind control, like the large man is logging in to her central nervous system and attaching himself to the base of her skull, shifting her identity and controlling her will. The man penetrates her brain in the same way that Kilgrave violates Jessica.

Throughout the film men try to grab, control or punish Thymian. They demand for her to “smile,” even when she’s suffering. They look at her like she’s food. They even hand out party pickles at a festive gathering (no idea why, but it seems abusive). All the while, Thymian is a force of self(ie).

Roger Ebert quotes Brooks in his review of Diary of a Lost Girl when he points out that she is all expressive stillness.

Says Ebert: “How she accomplishes this is the mystery of her acting. ‘The great art of films,’ [Brooks] wrote, ‘does not consist of descriptive movement of face and body but in the movements of thought and soul transmitted in a kind of intense isolation.’”

This soul transmission in “intense isolation” is the perfect definition of a selfie, before there were selfies.

In Diary, Louise Brooks gazes at the camera and the lens loves her. She dominates every lens she gazes into. She glows into the glass. I’d like to think that the light that fuels the film comes from her. Or at least it seems that way. Brooks is the living embodiment of a selfie-in-motion. She challenges the “male gaze” (the camera, the director, the audience, the men in the film) and the film’s eyes can only smile back at her. It’s especially obvious in silent film. The aged celluloid and the flickering cracks make every frame look like it’s weathered and worn down, shivering stills. The movement of the film isn’t fluid. It moves jagged edges all over Brooks, who remains angelic and preserved in her own light. But watch as the camera stays on her in deep close-up for decades. It has worn a smile for so long looking at her that the celluloid develops crow’s feet that crinkle around the edges of the movie.

It’s a deeply human medium, years of use and wear smiling under a natural “retro” filter at a woman who dominates every frame, even as her character suffers unspeakable abuse. The camera can’t physically cut or turn away, so it flickers on, selfie after selfie, each a loving documentation of a face pushing back. Brooks is triumphant because she never loses her self. She resembles Jessica Jones in her forced-smile-selfies for Kilgrave. But in Diary, the medium has become the message. It echoes Thymian’s recovery from trauma and rape. It empowers her to gaze back.