In their latest release, they conjure magic with a rich, intense, and sultry cover of Beyoncé’s Crazy In Love.

Read MoreVia Sonophonix

Via Sonophonix

In their latest release, they conjure magic with a rich, intense, and sultry cover of Beyoncé’s Crazy In Love.

Read More

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of several books, including Marys of the Sea, #Survivor (2020, The Operating System), and Killer Bob: A Love Story (2021, Vegetarian Alcoholic Press). They are the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault and received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

Read MoreBY MADISON MCKEEVER

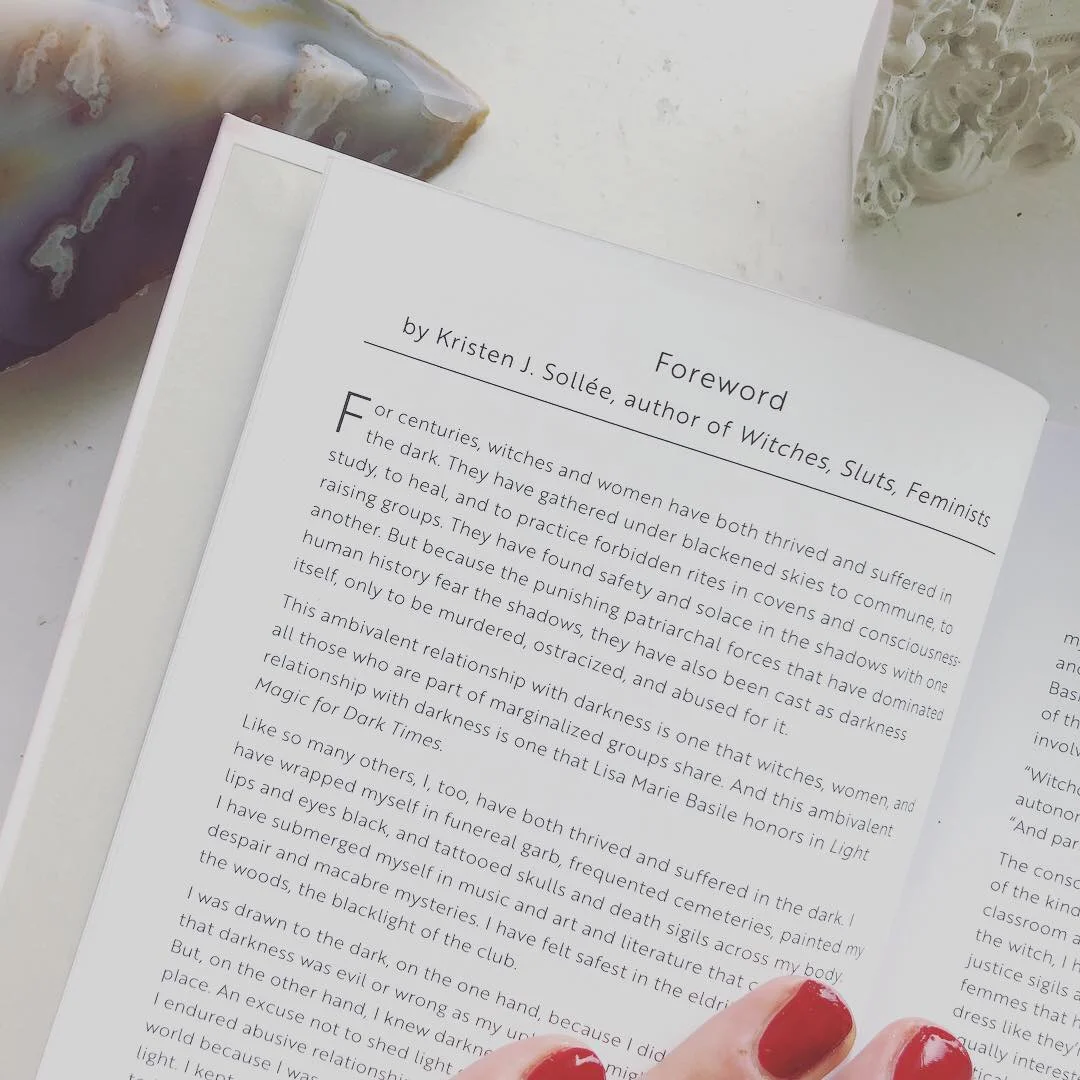

I’ve been fangirling over author and overall goddess Kristen Sollée ever since I first read her book, Witches, Sluts, Feminists: Conjuring the Sex Positive. Aptly named after just a few of the contested identities assigned to women who misbehave, Witches, Sluts, Feminists delves into the origins and intricacies of witch feminism and its intersection with reproductive rights, sexual pleasure, queer identity, porn, sex work, and many other topics.

From a historical perspective, witches have often been associated with specific cultural functions, either enchanting as feminist symbols of empowerment, or inspiring terror in a paranoid misogynistic Miller-esque fever dream. In recent years, witchcraft, magic, and other alternative spiritual practices have been the focus of increased attention and subsequent scrutiny, as people experiment and engage with feminism in all of its iterations.

Throughout her work, Kristen has spoken with countless activists, scholars, artists, and practitioners of witchcraft in order to enrich the public’s understanding of witch feminism and illustrate that witches in all forms, from Tituba to Stevie Nicks to Sabrina to The Hoodwitch, are powerful and relevant well beyond the month of October.

In addition to being a champion of female sexuality, Kristen is the founding editrix of the sex positive collective, Slutist (RIP), and is a gender studies lecturer at The New School. Her second book, Cat Call: Reclaiming the Feral Feminine: An Untamed History of the Cat Archetype in Myth and Magic was just released in September. Kristen herself is too fucking cool, whether she’s speaking out against SESTA/ FOSTA or rocking a killer purple lip on Instagram. She’s brilliant and generous enough with her time that earlier this year I had the pleasure of speaking with her about Witches, Sluts, Feminists, capitalism, and fighting for sexual liberation.

MM: How did you first become interested in the topic of witch feminism?

KS: It’s a long, circuitous story filled with both intention and magical intervention, but I’ve been interested in the occult since childhood, was raised by a feminist intuitive, and found my way to this subject first personally, and then professionally.

MM: What was the process of researching and writing this book like?

KS: Not pretty. Writing a book like this required confronting a lot of my own personal demons as I was interviewing dozens of people, scouring libraries and bookstores and websites for source material, and meditating on how I could do justice to a history so rife with pain and persecution that has been obscured and manipulated in numerous ways. It wasn’t something that was always fun or easy, but it was overall a joyful project to get to amplify voices that matter so much to me.

MM: In Witches, Sluts, Feminists, you polled 50 people about the definition of “witch,” and came back with a wide variety of answers. What’s your personal definition?

KS: The witch evades a single definition—that’s the beauty of the concept, really—but I will try! A lightning rod. A change-maker. A caretaker. Priestess of the persecuted. Harridan and hierophant. Rooted in the earthly and the astral. Fact and fiction, feminine and masculine, and so many things. The witch will forever be a shapeshifter.

MM: Do you think there is a generational/ geographical/ socio-economic connection to how the idea of the witch is viewed?

KS: Definitely. There are those who understand the witch to be an archetype of empowerment, those who see her as a Satanic seductress or a relic of religious persecution, and those who think she’s merely a cartoon hag to chuckle at on Halloween. It all depends on your own background and belief system and knowledge of the history.

MM: If you had to pick a witch or goddess that you’re most inspired by, who would it be?

KS: Oh there are so many, but I will pick a fictional one: Elvira. A witch who wields her sexuality in potent and playful ways. So many witches in fiction are so serious, she’s really a breath of fresh air. And a forever style icon as well!

MM: What are your “required reading” books for anyone looking to learn more about witch feminism?

KS: Silvia Federici’s Caliban and the Witch; Starhawk’s The Spiral Dance ; Maryse Conde’s I Tituba: Black Witch of Salem.

MM: Aside from reading, what are some resources for witches-in-training who are looking to educate themselves about practices, lineage, and history?

KS: Your local occult shop, or, if you don’t have one, The Hoodwitch’s online community. There are infinite folks to follow online, too, but some of my faves for inspiration and education in addition to @thehoodwitch are @themexicanwitch; @iamsarahpotter; @jaliessasipress.

MM: Do you see witch feminism as a lifestyle, a religion, or a hobby that can be shelved and called upon at times when it’s needed? I’m thinking primarily of practicing witchcraft in the age of Trump, and how many feminists are calling upon chanting, intention candles, hexes, and crystalogy as self-care rituals to heal from oppressive and toxic masculine government forces. Does witchcraft look different depending on what it’s needed for?

KS: Absolutely. Everyone’s spiritual and political practice looks different. There is no one way to use these powerful tools. Some folks don’t believe in mixing their witchcraft and their politics. Others believe witchcraft is specifically for healing and fighting oppression in the personal and political realms and that you cannot separate the two.

MM: Why do you think witches are so trendy right now? Is it because so many people need an ideology that centers around empowered women? Is it a form of escapism? Or are people just looking for a source of spiritual healing in a world that increasingly feels more and more hopeless?

KS: All of the above.

MM: How do you feel about the intersection in recent years between witchcraft and capitalism? In Witches, Sluts, Feminists you highlight multiple voices in the witch community and the disparate opinions on the topic, but you also point out that, “the witch is ‘the embodiment of a world of female subjects that capitalism had to destroy’ in order for the reigning economic order to triumph” (132). What are the implications of capitalism co-opting witchcraft without educating consumers about the origins of their purchase? (ahem, Sephora)

KS: I am quoting Silvia Federici there, but yes, it is very necessary to address capitalism’s co-optation of witchcraft and the occult, particularly when workers (often women in sweatshops around the world) are actively harmed in the making of “witchy” products and when closed, indigenous practices are being stolen from in the process. That’s not witchcraft, it’s exploitation.

MM: What are your feelings on Trump’s ironic and often repeated use of the term “witch-hunt” in reference to himself and the media? I think the linguistic significance of this is fascinating based on what it entails, historically- speaking.

KS: Like much of what Trump says, it’s a horrendous distortion of historical fact. It also goes to show how much misinformation there is about what “witch hunts” actually were—and are today.

MM: One of the popular phrases that has gotten circulated across social media and throughout women’s marches in the last year reads (in some iteration), “Nasty Women are the granddaughters of the witches you couldn’t burn.” Considering this and the prevalence of witch and goddess energy within the #metoo movement, do you think the spiritual and the political can intersect for the greater good?

KS: Absolutely, as long as the spiritual doesn’t become dogmatic. There still has to be room for spiritual and religious dissent and plurality or we’re no different than the religious right.

MM: I’m fascinated by the sexual connotations of American witch history, how witches were seen as harnessing an impure (ie. un-Christian) sexual appetite, and how the deeply patriarchal nature of early New England allowed this ideology to perpetuate until people were put to death. Can you speak more about how and why you think a deep-seated fear of female sexuality exists?

KS: Patriarchal religion—in America’s case Christianity—is at fault for this one. When you have an origin story that places female desire as the root of pain and suffering (hello, Eve) you’re not off to a very good start, you know?

MM: Why do you think the world seems to be threatened by sexually enlightened womxn, or womxn who unabashedly identify as sluts? Are sluts viewed as a threat to masculinity because subverting the terminology pushes back against the misogyny of our government and world?

KS: Being unapologetic about your sexuality or your body as a woman or a person on the feminine spectrum remains so radical because it counters everything that patriarchal society dictates about the masculine dominating the feminine.

MM: Are “witch,” “slut,” and “feminist” synonymous terms?

KS: No, I don’t think so, although there is great overlap between them depending on culture and context. To me, they are beautifully complex, complimentary terms.

MM: Do you think the meteoric rise of witches will continue indefinitely?

KS: Witches may not be splashed across The New York Times forever, but they certainly aren’t going anywhere anytime soon. And thank goddess for that.

Madison McKeever is a writer based in New York City. She probably wants to ask what your favorite book is. She's passionate about true crime, Timothee Chalamet's sartorial decisions, Instagram cats, and talking about the orgasm gap. Find her @thesleepygirlscout

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body), #Survivor, (forthcoming, The Operating System), and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

Monique Quintana is a Xicana writer and the author of the novella, Cenote City (Clash Books, 2019). She is an Associate Editor at Luna Luna Magazine, Fiction Editor at Five 2 One Magazine, and a pop culture contributor at Clash Books. She has received fellowships from the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley, the Sundress Academy of the Arts, and has been nominated for Best of the Net. Her work has appeared in Queen Mob's Tea House, Winter Tangerine, Grimoire, Dream Pop, Bordersenses, and Acentos Review, among other publications. You can find her at moniquequintana.com and on Twitter @quintanagothic.

Read More

BY MARY KAY MCBRAYER

*SPOILERS*

I have to confess something about Ari Aster’s new movie Midsommar: I did not identify with or even like Dani until she chose to set her boyfriend on fire. Before you judge me as a vindictive arsonist/murderer, hear me out. Most of my re-alignment with the protagonist is because of the ritual of dance.

I have been a dancer for all of my life—one of my earliest memories is being in a pink leotard at three years old and hearing my instructor say, “If you ever lose your place, just listen to the music. It will tell you where you are.” She meant that we should listen to the counts to situate ourselves in the choreography, but I didn’t take it that way, not even then. There’s something really special about being able to lose yourself in a piece of music, especially when the music is live. It shuts off the rest of your brain and makes you live in your body, and you kind of forget everything that is happening if it isn’t the dance. And when you finish dancing, everything falls in its place.

I remember at one convention I went to, the keynote speaker (Donna Mejia) asked the crowd, “How many of you feel like you are wasting time when you’re dancing? That you should be doing something else?” Nearly everyone raised her hand. “Now, how many of you are only truly happy when you’re dancing?” I did not see a single hand go down.

Sure, it sounds like a lot of existential gibberish if you haven’t experienced it—but let me ask this, more relatable question: have you ever been drunk and lost yourself on the dance floor of the club? (Look at me in the face and tell me you have never suddenly heard the end of a Prince song and realized you were grinding on a stranger in the corner. LOOK ME IN THE EYE. And tell me that.) My point is, when we hear someone is a dancer, we think they are a performer, but that is not necessarily the purpose of dance, not spiritually, and not in Midsommar.

Another confession: most of my dance training is in Middle Eastern dance, which is very different from Swedish dance, but the folk music and dance, and the purposes of it, are not necessarily THAT different. For example, belly dancing originated with women dancing for and with other women. There was no one watching. There was no audience. Everyone danced. It was a form of community. It’s the same community you feel dancing in the kitchen in your pajamas with a couple of close friends. That feeling, the one of being among your friends and doing your hoeish-est dance with a spatula in one hand is the BEST, and it’s what we see in Midsommar with the Hårgalåten. In my experience, that’s when you really start dancing, when you forget that people are watching, listen to the music, and express it in your physicality.

When women dance like that, we don’t care what we look like because no one is supposed to be watching. If they are watching, they don’t stop dancing to do it. And that’s powerful. No one is watching me. Everyone is dancing with me. I am dancing with everyone. No one is watching me, and I don’t care what I look like. (Great performers are the ones who harness this and utilize it onstage, even though there ARE people watching.) You can see the moment that Dani realizes the happiness that come with the May Day dance in Midsommar. It is the first time she smiles in the whole film.

So many of us, too, think that dancing is about the viewer, but it just isn’t. Not on a fundamental level. Sure, dance can be a performance, but that, to me, is not its purpose, and it’s definitely not the purpose of the movie Midsommar’s dance sequence. To me, the purpose of the whole May Day/May Queen dance around the May Pole is to show Dani her true family.

These women embrace her, they let her be a part of their dance community, and that’s so powerful—I’ll never forget the first time a dancer pulled me into the circle of a folk dance. It was magic. I, like Dani, glanced away a couple times to see if anyone was watching.

She wants Christian to be watching, but he isn’t. It seems like she EXPECTS to be sad that he is not paying attention, but then her dancing becomes even more joyful, more spiritual. (You can see this emotional fortitude, though not joy specifically, in spiritual dance rituals around the world, from the Whirling Dervishes in Turkey to the Moribayasa dance in Guinea to the May Day Hårgalåten celebration in the movie Midsommar.)

In the Hårgalåten, the women ARE having fun, though. Though it’s a competition, they are not really competing. Or at least they are not competing with each other.

In the folktale of Hårgalåten, the devil disguised himself as a fiddler and played a tune so compelling that all the women in Hårga danced until they died. In the version that Midsommar tells, the dance ritual is a reenactment of that myth. The women knock each other down because they’re shrooming so hard they run into each other when the music changes. They aren’t mad, though, when they fall. They tumble down, laughing, and roll out of the path of the remaining dancers. The last one standing, one of the villagers says to Dani, is the May Queen.

The May Queen, in the context of the film, has some pretty dark and ominous foreshadowing around her. I assumed, at the first appearance of that archetype, that the May Queen would be sacrificed, and I think that is what the film wants us to assume. That is not, however, what happens, and I was glad of it. (So much of this film is not what I expected it to be, and that is a delight among formulaic horror movies.)

Even the song of the Hårga is told from the first person plural, the “we” of the dancers. They are all invested in the ritual. If one of them wins, they all win. When Dani is the last dancer standing, her new family celebrates with her. They are there for her when she grieves her boyfriend, too.

I love the ending of Midsommar because I feel like Dani really comes into her own; it’s the first time she’s had agency or presented with a choice, in my opinion, throughout the film. As you know, the May Queen is not sacrificed as many of us likely intuited: instead, she’s lifted on a platform and carried to her flower throne. She follows the sounds of another ritual though her now-sisters advise her against it. They go with her anyway. She sees her boyfriend having sex with someone else. She hyperventilates. Her new family is there, with her, breathing with her and comforting her in an empathy so physical it’s uncomfortable to the viewer.

Then, Dani discovers that the May Queen gets to choose the final sacrifice, from between Christian and a member of her new family. She chooses her boyfriend.

Here’s the thing, though: I don’t think she chooses him because he’s “cheating” on her. That ritual, to me, is absolutely a rape, for one. That Christian has a terrible time at the festival is a gross understatement, but the thing to remember is that Christian was shitty way before they came to Sweden, and Dani, like so many women complacent in their relationships, women clinging to a dysfunctional relationship because the rest of their world has crashed, women set adrift from the world, clings to him like a life raft, even though he will not keep her afloat.

During the dance, Dani finds support, love, joy, and that is (in my interpretation of the competition) why she wins. It’s not until she finds that community in Hårga, specifically in the dance with the other women, that she can release the last tether to her unhappiness and set him on fire.

Mary Kay McBrayer is a belly-dancer, horror enthusiast, sideshow lover, and literature professor from south of Atlanta. Her book about America’s first female serial killer is forthcoming from Mango Publishing, and you can hear her analysis (and jokes) about scary movies on her blog and the podcast she co-founded, Everything Trying to Kill You.

She can be reached at mary.kay.mcbrayer@gmail.com.

Astrolushes is a podcast at the intersection of astrology and literature, ritual, wellness, pop culture, creativity — and, of course, wine. Expect guests, giveaways, & games — and get ready to go deep with us.

The water-sign hosts are Andi Talarico, poet, book reviewer and Strega (@anditalarico) & Lisa Marie Basile, poet, author of Light Magic for Dark Times, & editor of Luna Luna Magazine (@lisamariebasile + @lunalunamag). You can the astrolushes on Twitter, too, here.

LISA MARIE BASILE: Let’s chat about the birth of AstroLushes! I think it sort of started on a drive we took to Salem, MA, where we witched out for a weekend and visited HausWitch for my Light Magic for Dark Times writing workshop. In the car, I threw celebrity and literary names at you and had you guess their big 3 signs. You were amazingly on point! I'm wondering, besides having fun with it, what do you personally think the 'use' or 'reason' for this astro-knowledge is? I think people are generally fascinated, but we both know there's more to it.

ANDI TALARICO: That road trip and our time in Salem definitely feels like the genesis of this show! It started with us guessing celebrity's charts and now it's just a part of all of our conversations. I feel like now we're constantly wondering about writers and actors and philosophers through the lens of their astrological placements. It's a fun game but I think it also allows for a possibly deeper understanding of the art and culture that we engage with.

And engagement was how I came to astrology. My mother always read our horoscopes from the paper when I was growing up; she's a mystical Pisces who has visited psychics, believes in prophetic dreams, and finds herself fascinated by the moon. I inherited a lot of my curiosity from her. But by age 12 our household had changed considerably and it became a harder place to exist and grow in. So it's no surprise to me, looking back, why that was the time I started studying astrology.

It was a way of making sense of the world. It also gave me an opportunity to talk to people about themselves (and to keep the focus off of myself.) It made me feel like I had some sort of agency, a voice, a new authority. Now, the language of astrology, to me, is less about telling people about themselves and actually, much like my tarot practice, using the themes and ideas as lessons that we can use to fully become our best, most authentic selves. That's where it crosses over into self-care as well.

How do you feel about people who think astrology is bogus, Lisa?

Astrology…much like tarot practice, uses the themes and ideas as lessons that we can use to fully become our best, most authentic selves. That's where it crosses over into self-care as well. — Andi Talarico

LISA MARIE BASILE: I love that you say it's an engagement with everything around us. And that, as a child, it helped you navigate a very difficult world. It truly is a language we learn and then we speak, and that can bring people together in an instant. And it can help us focus on the many characteristics of ourselves. In my life, processing the trauma I've experienced through the filter of the Scorpio has been amazingly beneficial; I now look on it all as transformative, rather than destructive.

It's also really interesting to give a name to the various inclinations and motivations for people's art or behaviors. Especially when you look at creative people, or really evil people, and you start seeing how many of them fit into a certain astrological sign, or element. It may not be scientifically proven, but that’s the sort of mystery and liminality that we derive meaning from.

I am a scientific person. I believe that reason, empirical evidence, and research is important. I live with a chronic illness, and I'm a health writer as a day job. It's important to me that information is disseminated accurately, or, say, that the injections I take have been proven both effective and safe, and that sometimes, you need medication over meditation, in order to heal.

At the same time — people need to know there’s more to health and wellness than big pharma. And there’s more to this world than what we can see. I think the zodiac allows us to approach the liminal, the intuitive, the subterranean. It does exist outside of 'objective science' and that's okay. It allows us to dive headfirst into the shadows of this world and our lives, and I think that's the key to the feeling whole — straddling both sides. Science has a place, but so does the esoteric. You can't prove love, but we all feel it. So, it's the same thing. Some things we just explore knowing that it may be obscure. I am grateful to be able to take part in the world from both stances.

What do you think about how people can use the zodiac as a healing tool, or in daily ritual?

There more to this world than what we can see. I think the zodiac allows us to approach the liminal, the intuitive, the subterranean. It exists outside of 'objective science' and that's okay. It allows us to dive headfirst into the shadows of this world and our lives, and I think that's the key to the feeling whole — straddling both sides. Science has a place, but so does the esoteric. You can't prove love, but we all feel it. — LISA MARIE BASILE

View this post on InstagramSunday afternoons at home. 📸 by @michaelsterling

A post shared by Andi Talarico (@anditalarico) on

ANDI TALARICO: I definitely look through several horoscopes during the morning to see what my day/week might bring me. I mean, the basis of horoscopes are transits, what the movement of the current celestial journey means in my zodiac placements, and I love that about horoscopes — how it's a constant reminder that everything changes, nothing stays still, and how cyclical life can be, for good or bad.

I like to look to the planets/celestial bodies and their assigned western astrological associations for greater personal meeting. Like, what does it mean to be represented, as I am, by the Moon? The Moon shines because it reflects the light that is given to it. I feel the same way, again, for good and bad. I also shine brightest when I'm basking in the the light of stimulating conversation and affection. I turn inward and dark when I'm not given light to work with.

Also, since the Moon transits more often than other bodies, since it's constantly waxing or waning, it serves as a beautiful remind to keep pushing forward, that this moment isn't forever, to enjoy the view and perspective before it changes yet again. It's why I have a little crescent moon tattooed on my finger — my constant reminder that the only constant is change.

How do you feel connected or represented by Pluto, Lisa? Pluto is such a symbolically important planet of creative destruction, I'd love to hear your thoughts on that!

What does it mean to be represented, as I am, by the Moon? The Moon shines because it reflects the light that is given to it. I feel the same way, again, for good and bad. I also shine brightest when I'm basking in the the light of stimulating conversation and affection. I turn inward and dark when I'm not given light to work with. — ANDI TALARICO

LISA MARIE BASILE: Oh, that’s so beautiful! When you say, “I turn inward and dark when I'm not given light to work with,” I feel that in my core! I love the idea of this cosmic duality, how it represents the shadowy quietude and the display of light. It reminds me that we are all just star stuff. It’s why I started Luna Luna!

It’s funny you mention the tattoo, because I have one that also reminds me that things change; it’s an ampersand. Maybe that’s why you and I are so drawn astrology? That it provides a foundation we can find stability in but the fluidity we need to always be growing.

I think the fact that Pluto has been considered a planet, a not-planet, an exoplanet and whatever else, is very beautiful—a perfect and living representation of Pluto as a symbol: it dies and is reborn, and yet it remains this beautiful archetype of transformation, weathering the storms of idea and rule and order. Could literally anything be more perfect?

Pluto is my beautiful ruler, and I am indebted to its reminders. I have always been able to die and rise. I lean into the dark and then I die. I go into dark periods of change and emerge. I almost need it more than the light. But I suppose, that is my language. The darkness becomes a kind of light that makes sense.

I think that’s the beauty of this cosmic story. No matter what you believe or feel skeptical about, astrology’s narrative, symbolism and reminder to explore the grandness of human emotion and circumstance is all splayed out up there. We just need to look up.

What do you think about people who say they they believe in astrology and make Huge Life Decisions around it? Do you think it’s important to figure astrology into your day to day? Jobs? Dates? Etc? Or do you think it serves its best purpose as a tool for introspection, rather than a rulebook?

No matter what you believe or feel skeptical about, astrology’s narrative, symbolism and reminder to explore the grandness of human emotion and circumstance is all splayed out up there. We just need to look up. — LISA MARIE BASILE

ANDI TALARICO: LOVE this: "...Pluto as a symbol: it dies and is reborn, and yet it remains this beautiful archetype of transformation, weathering the storms of idea and rule and order. "

As for me, I don't make huge life decisions based on astrology in the sense, that, say, I won't work with people of certain signs or judge them based on their natal chart. The idea of not dating this sign or that sign is a prejudice to me, and unfair. Even knowing someone's chart information is an act of intimacy — that's private knowledge — and to use it against someone or to think you know everything about a person based on it...hell no. Absolutely not.

Can it help you locate potential challenges? Yes, I believe that. Is is exciting when your synastry is in alignment and looks positive? Of course. But we're all much more than our natal charts. We're our upbringing, we're our ancestors, we're survivors, we're our good days and bad days, we're what we've been allowed to be and what we've rebelled against. Our zodiac signs matter but they don't make or break us.

I WILL make decisions based on transits and the moon's phases, though. Like, new beginnings during the new moon — that just makes sense to my entire being, both my physical and spiritual self. I definitely believe in harnessing the new energy at the start of a new zodiac phase — focus on good communication at the start of Gemini season! Make those spreadsheets in honor of Virgos everywhere! Get real sexy at Scorpio time!

But, would I, say, not send an important email when Mercury's in Retrograde? No, I try not to rely THAT heavily on astrology. I try to use it more as a guide and tool for learning than a strict rulebook. But...I also hate rules and authority in general. I naturally bristle against those who think they have the exact answers, at least in areas that don't involve exactitude and true yes or no areas. I'm a skeptical human, in many ways.

Is is exciting when your synastry is in alignment and looks positive? Of course. But we're all much more than our natal charts. We're our upbringing, we're our ancestors, we're survivors, we're our good days and bad days, we're what we've been allowed to be and what we've rebelled against. Our zodiac signs matter but they don't make or break us. — ANDI TALARICO

Image by Ignacio Martinez Egea

**Monique Quintana** is the author of Cenote City(Clash Books, 2019), Associate Editor at Luna Luna Magazine, and Fiction Editor at Five 2 One Magazine. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from CSU Fresno and is an alumna of Sundress Academy for the Arts and the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley. Her work has appeared in Queen Mobs Teahouse, Winter Tangerine, Dream Pop, Grimoire, and the Acentos Review, among other publications. You can find her at [moniquequintana.com][1]

Read More

Image via Tori Amos

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

You don’t need my voice girl, you have your own

We were living in a poor neighborhood on the border of Elizabeth and Newark in New Jersey. I took packed “dollar cabs” to school when it was too cold to walk. We used food stamps at the little mercado downstairs, so I only went when my friends went home and I wouldn’t get caught.

On the third floor, our little apartment had two small bedrooms. Mom slept in the living room, on the couch. My mom was always either at the mall working, or out. She was working hard to overcome an addiction, and no matter how big and beautiful her heart was — the monster was winning. When she was out, I would, like a cat, keep an eye or ear open. Hearing the door knob late at night meant I could finally rest. She was home, and my body could wilt. I could sleep.

My brother and I slept on mattresses on the floor; his room got even less light than my did, so he would sit on the floor playing video games for hours in the dark. I could feel the house’s sadness all the way from my bedroom, but I didn’t have the language to manage it. The translation was lost in the heavy air, so I’d shut my bedroom door and ignore him, seven years younger than me. I’d blast my music and pretend to be somewhere else — in the woods, at the sea, wherever I could be free.

My room was my heaven. There was one long window, and that window looked out at a yard where I could watch a neighbor’s dog lounging or chasing butterflies in the summer. In the smallest of ways, everything felt fine. I could siphon that normalcy and try to press it into my chest like a lantern. I’d light it up when I couldn’t sleep.

A room is a sanctuary, an ecosystem, a confessional.For me, it was a place where I transformed from wound into girl.

Tori Amos happened to me during the summer of 1999. I’m not sure how it happened or who recommended her to me, but when I slipped the little Under the Pink disc into the CD player and sat on my bed, I grew a new organ. I was capable of metabolizing the trauma.

When my mother was out, out, out — wherever she was — or when she was in a screaming match with her violent boyfriend in the next room — I was etching Tori’s lyrics, sometimes over and over, into a little notebook.

I couldn’t possibly have understood all of it, as most of the language was either too adult or too cryptic or simply too Tori, but it spoke directly to the wound in a way that needed no translation or filter.

It was the line, You don’t need my voice girl you have your own, that I distinctly connected with. I wasn’t aware of what feminism really meant, not at all at that age or in that era, but I could feel the surge of electricity that came with being validated by a woman. I was suddenly her little cousin, and Tori was my cool older relative — all jeans and red hair exuding some strange, beautiful warmth. Or maybe she was my stand-in mother. My goddess. It was one of my first glimpses of what it could mean to look up to a woman who was full of space and light and hurt, like me, and who, through some digital osmosis could also heal and love me. Who tapped into the small dark pain and cradled it.

My mother was sick. My grandmother was dying. I had no one else I could turn to, but Tori found me in my bedroom and inhabited the space as nightlight, as cool sheets, as framed photographs of possibility.

Another element that struck me: the odd narratives. At this point, I was existing in the height of teen melodrama. A word could mean a million things. A lyric could mean anything I needed it to be. And an album could be the digital imprint of my entire life. I didn’t try to dissect the words, as an adult would. Instead, I fell, backwards into her words; it didn’t matter if I didn’t ‘get it’ or if I had no idea who the fuck the grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia was. I hung onto every word because my life was small and broken and dirty, and Tori gave me everything and more. Continents and ghosts and heartache I wouldn’t experience until I was older.

So, of course I’d borrow a computer at school to Ask Jeeves the Duchess, and I’d print out about 28 pages describing the whole history of her life and death. With my newfound Tori knowledge, I’d walk around the halls at school clutching her lyrics and all the weird shit the Internet said about her work as if they were holy texts. I had the secret. I had a bigness in my pocket. I had possibility and potential and the mouth of the piano whispering into my ears.

Really, as long as I had double-A batteries for my disc-man I could move through my day cushioned.

It was around this time I started writing poetry. I often borrowed themes and topics from Tori’s music, becoming obsessed by her stories of sneaking sexual acts and rebelling against religious morals — getting off, getting off, while they’re all downstairs — or her not-so-cryptic words about God — God sometimes you just don't come through/Do you need a woman to look after you? My poems might have been bad, but they turned my sad, small little bedroom into a palace of courage.

Her bravado and bravery asked me to confront things I’d been afraid to think of. For one — god. Raised in a Catholic family of Sicilian descent, the idea of God and morality and shame was stamped into me since childhood. Even if I wasn’t at church every Sunday, I’d never really heard anyone so thoughtfully critique god. (Pretty soon I’d stumble on Tool’s Aenima, but Tori got to me first).

Also round this time I was making out with bad boys who smelled like cigarettes and pulled fire alarms. I was skipping class to hang out with girls I crushed on. I was *69ing calls in the hopes it was a boy. But talking about sex with any seriousness was not the norm. Tori talked about it from the woman’s perspective, and not just in relation to getting fucked by a guy. Her frankness, especially around masturbation, positioned sensuality as something that wasn’t dirty or bad, but sacred and empowered. Reclaiming, exploratory, rebellious. Hers.

Because I started with Under the Pink, I quickly moved on to Little Earthquakes and found out quickly that she had some powerful words around sexual assault. Yet again I was able to confront the massive, festering wound that I’d been carrying around since pre-adolescence, when I was assaulted (repeatedly) by a man in his 40s.

For me, Tori Amos allowed me to inhabit myself. And myself was a place which was always kept burdened by realities far too heavy for what a teenage girl should have to carry.

Tori, for me, was like an early archetype of Hecate, my goddess of night, of ghosts, bringing me into realms where I could confront the dark. She lit the way through my journey.

The strangeness and complexity of her music, the choir girl influence, the jarring juxtapositions, her softness of anger and brightness of disappointment — it was a new language. Between those first and last tracks, an angel’s wings unfurled, alighting a bleak space.

She taught me that words — stories, poems, or lyrics — could be nuanced and odd and nonlinear, rooted in magic and not saturated in a sugary shell for easy consumption.

But most of all Under the Pink taught me that in self-truth, no matter how messy or imperfect or grandiose or weird, a whole spectrum of color could unfold. There I was in yellow, in blue, in lilac. I experienced a shadow life in color. There I was stepping out of my own dark, even for a few moments.

You don’t need my voice girl, you have your own, she said. And I believed it.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by Lisa Marie Basile (@lisamariebasile) on

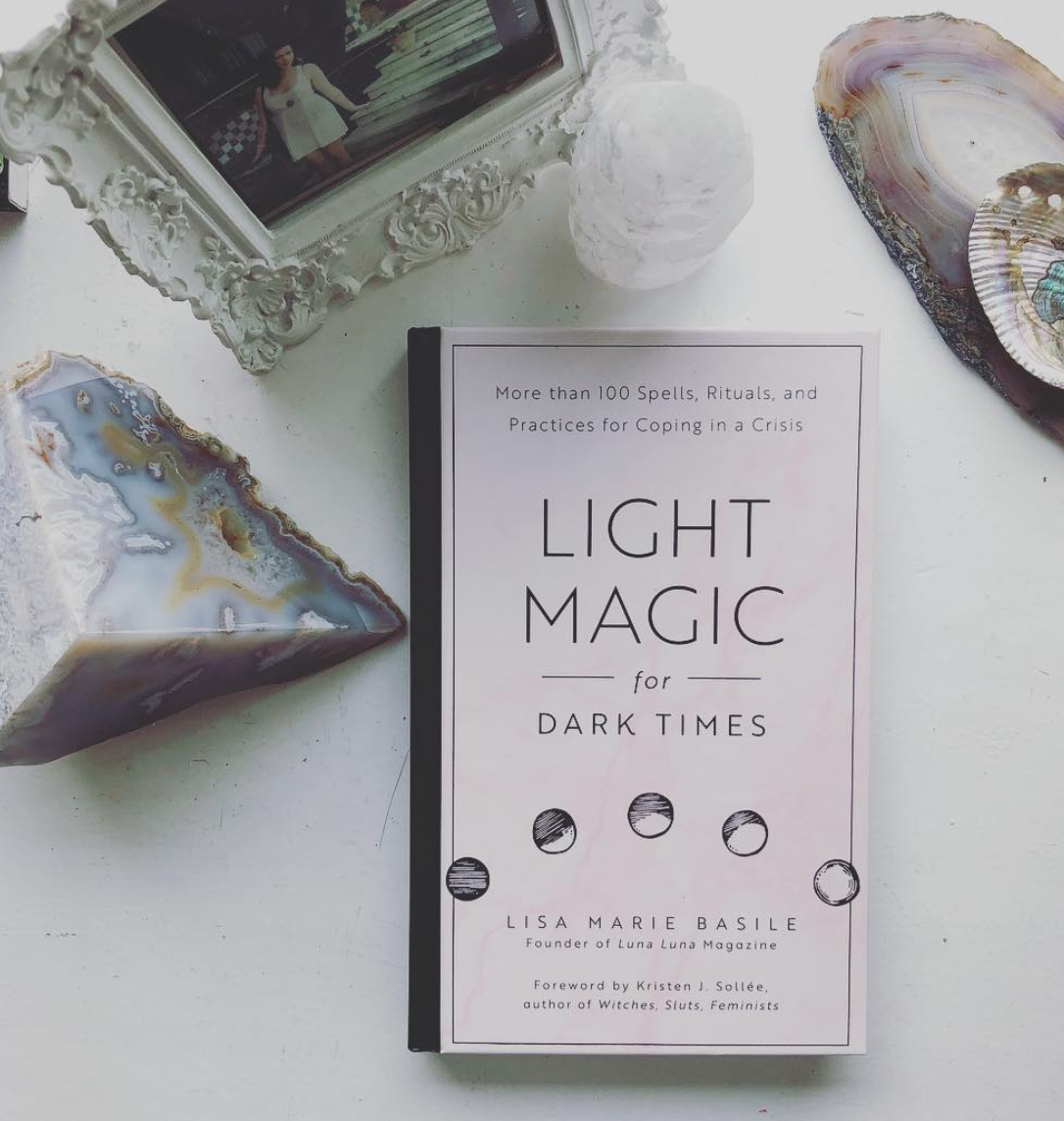

Lisa Marie Basile is the founding creative director of Luna Luna Magazine—a digital diary of literature, magical living and idea. She is the author of "Light Magic for Dark Times," a modern collection of inspired rituals and daily practices. She's also the author of a few poetry collections, including 2018's "Nympholepsy."

Her work encounters the intersection of ritual, wellness, chronic illness, overcoming trauma, and creativity, and she has written for The New York Times, Narratively, Sabat Magazine, Healthline, The Establishment, Refinery 29, Bust, Hello Giggles, and more. Her work can be seen in Best Small Fictions, Best American Experimental Writing, and several other anthologies. Lisa Marie earned a Masters degree in Writing from The New School and studied literature and psychology as an undergraduate at Pace University.

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

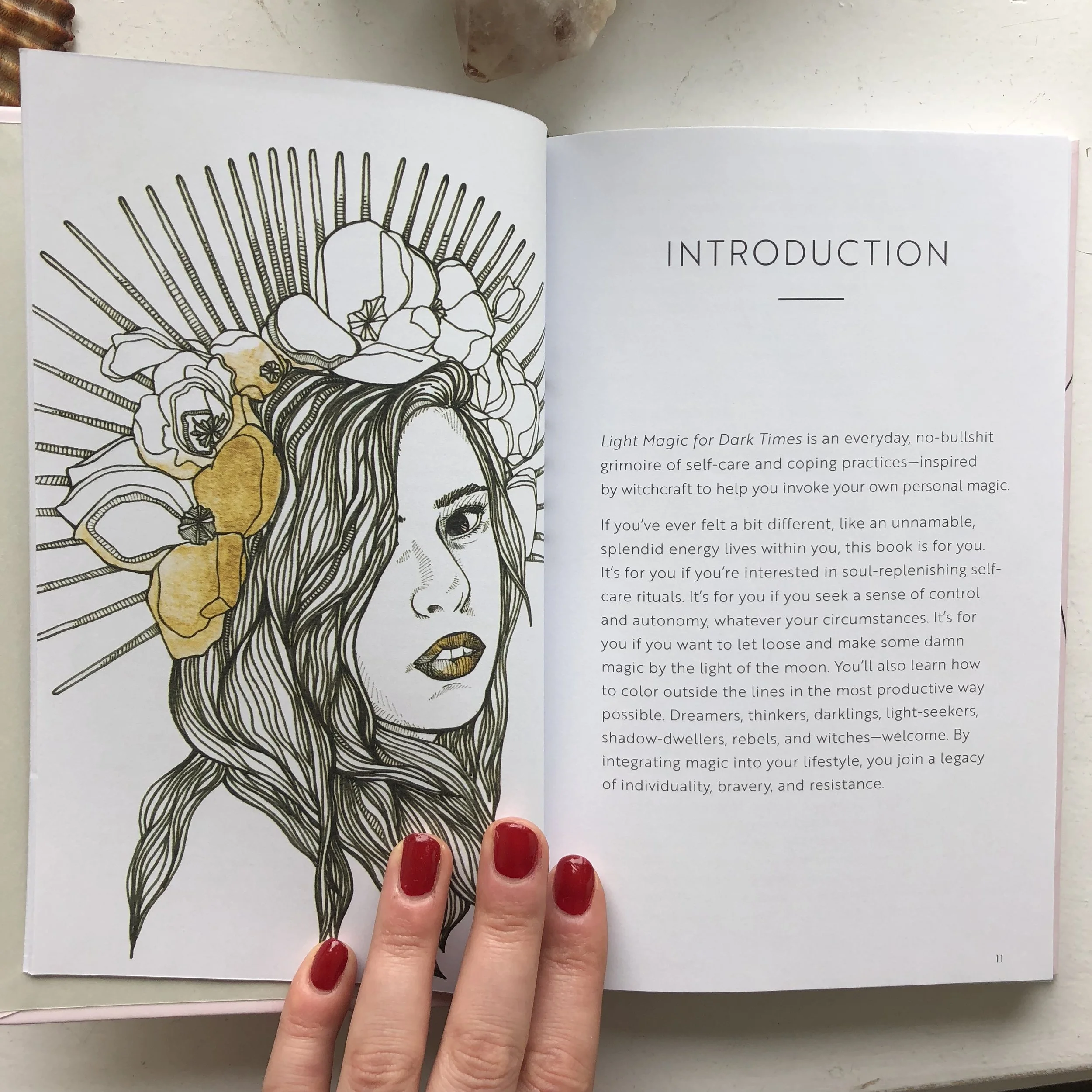

Welcome to a sneak peak of my grimoire of self-development and ritualized living!

Though the archetype of the witch is part of what inspired LIGHT MAGIC FOR DARK TIMES, it’s also a book of what inspired me about people I love and care for, like my mother, who has had to grow and regrow several times over; like the people I know who have used their voice for personal and community change in the face of systemic oppression. It’s a book of love and care, of rebellion, of reclamation, and growth. That energy is magic.

I wrote LMDT after an editor actually spied a ritual of mine here at Luna Luna and asked me to expand on it— and so it is, in many ways, the unofficial Luna Luna grimoire.

Here are all the places you can pick up the book. And here’s a look at what’s inside:

View this post on InstagramA post shared by Light Magic For Dark Times (@lightmagic_darktimes) on

Light Magic for Dark Times is all about ritualizing your life and finding your inner magic — by embracing the light and the shadow together.

It was written as a guide through the self.

The chapters cover everything from journaling and sigil creation to finding your own personal magic and integrating daily ritual.

The foreword was written by the inimitable Kristen J. Sollée. You should read her book, Witches, Sluts, Feminists: Conjuring The Sex Positive.

Because I’m a poet, you’ll see a lot of literary references woven throughout the book.

Light Magic for Dark Times is for the rebels, dreamers, shadow-dwellers, thinkers, darklings, & light-seekers amongst us.

You can find more inside peeks below

View this post on InstagramA post shared by Light Magic For Dark Times (@lightmagic_darktimes) on

View this post on InstagramA post shared by Light Magic For Dark Times (@lightmagic_darktimes) on

View this post on InstagramA post shared by Light Magic For Dark Times (@lightmagic_darktimes) on

View this post on InstagramA post shared by Light Magic For Dark Times (@lightmagic_darktimes) on

Lisa Marie Basile is the founding creative director of Luna Luna Magazine and the most recently the author of "Light Magic for Dark Times” and "Nympholepsy." Her work encounters the intersection of ritual, wellness, chronic illness, overcoming trauma, and creativity, and she has written for The New York Times, Narratively, Sabat Magazine, Healthline, The Establishment, Refinery 29, Bust, Hello Giggles, and more. Her work can be seen in Best Small Fictions, Best American Experimental Writing, and several other anthologies. Lisa Marie earned a Masters degree in Writing from The New School and studied literature and psychology as an undergraduate at Pace University.

When I was a teen, my hobbies were a little singular. I loved moodily soaking in the bathtub in the middle of the night and wearing my pajamas well into the afternoon. Back then, this was the kind of behavior that led to my family and friends teasing me, constantly asking why I wasn’t hanging out at the neighborhood Arby’s like everyone else. But, it seems nightgowns are making a comeback (and perhaps they have been for a while now). In honor of Lana Del Rey’s new song, “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have” here’s a list of some of my favorite nightwear in the media, and some links so you can get yourself a nightgown to tear around in well into the afternoon.

Read More

Photo: Joanna C. Valente

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, & Xenos, No(body) (forthcoming, Madhouse Press, 2019) and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes, Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente

BY DEIRDRE COYLE

When I watched the first episode of Le Balm—the new web series by Cecilia Corrigan and Monica Nelson—I cackled, then anxiously touched my face to check the quality of my skin, then cackled some more. Le Balm follows a makeup vlogger named Madeleine who decides, after the 2016 presidential election, to convert her many followers into radical activists by smuggling coded messages about overthrowing the regime into her beauty product reviews and tutorials.

In the past year, women's media has been full of articles on self-care as both coping mechanism and radical act. Le Balm questions the validity of this rhetoric with dark humor and compassion. As Corrigan wrote to me in an email, "Dealing with questions about complicity, beauty standards, and the privilege of self-care in a time of political disruption, the series brings together the worlds of our current political climate of anxiety and the messages of women's beauty culture."

Despite a shaky connection between New York and Los Angeles, I video chatted with Cecilia and Monica in the hours before their West Coast launch party.

So I first wanted to ask how you came together to work on this project, and where you’re both coming from?

Cecilia: I met Monica when we were both working on another short film, Crush, which was another piece that played with dark comedy to critique a certain sector of culture—in that case, the art world. We have pretty different backgrounds—my background is academic, and I started out in poetry, now I write and perform weird comedy, and Monica has been working in branding and advertising for years.

Monica: Different backgrounds, for sure. But we share an interest in using narrative and humor to make a cultural critique, that’s sort of the space where every idea we tossed around landed. Cecilia is amazing at creating these intuitive comedic characters that mirror back a very honest reality.

Cecilia: One of the things I like about this character is that she’s almost uncomfortably familiar, like she’s just taking the idea that self-care can be a radical political act to its natural conclusion. So even though it’s parody, it also feels uncanny. I think we were interested in that discomfort.

Monica: Yeah, and there is truth to it as well. The idea for Le Balm started at a women’s group that was organized the week after the election. Everyone was trying to figure out how to respond. Then Cecilia was kind of joking about doing a beauty guru character who’s having a political awakening after the election, and I was like "we should actually do that." That’s how Le Balm got started.

Cecilia: Yeah, that group was cool; I know a few similar groups cropped up that winter. This one was called Feminists Against Fascism—it was all women, a lot of them worked in media, many of them were activists. I found myself thinking about the beauty industry and "women’s media" a lot at that time, and about the idea of a coastal elite. The election brought so much misogyny to the surface, but also revealed so many of the limitations of a feminist politics that isn’t intersectional.

In a way, is this character in Le Balm also grappling with these questions?

Monica: Yeah, in her own way. She’s just taking it very, very literally.

Cecilia: It definitely comes from a relatable place. I first got the idea in a moment of recognizing my own ridiculousness, when I caught myself deeply stressing out about whether I should switch my moisturizer with the changing climate, and simultaneously freaking out about the terrifying political changes that seemed to be already affecting vulnerable people in a really immediate way. I was like, "wow I’m the worst." And you know, I think one of the things that saves me from going crazy is laughing at myself.

Monica: The idea of using what we know, and our own personal experiences seemed really important. I was shaken by the way that women were receiving information, and how it was being framed. All of a sudden all women’s media outlets turned to women’s causes, and you would literally read an article about a social justice cause and a moisturizer in the same typeface and tone. I still have screenshots from that time period that we would send back and forth. Literally posting these headlines that were like, "Are you bleary eyed because of the news? Here are some eye brightener tips."

RELATED: Interview with Sarah Forbes, the Curator of Sex

I did want to ask about the character. We don’t actually learn much about her background in the show, her story before she deleted all of her social media and then restarted it. But clearly she’s a privileged character: a young, attractive white woman able to make her living vlogging (she talks about her sponsorships in the first episode). Could you talk a little about how this character’s conception of "radical activism" is informed by these advantages?

Monica: This girl is earnest. That’s something that’s really important to us. This character did kind of exist in this bubble before the election. She was very sheltered and was able to create this whole ecosystem that was just hers. Her aesthetic was probably a little more decadent, or kitsch. But then her world was sort of blown. When we were briefing the team for the shoot, I would say "Imagine a girl that discovered politics and Garance Doré in the same day."

Cecilia: Yeah. She was definitely in a bubble before. I think a lot of people with a certain kind of privileged complacency felt like they had to become political, become "woke," right after the election. I imagined that whatever was going on with her in the lead-up to this moment, like whatever happened between the election and her new videos, was probably pretty messy. I think this is more than just a re-brand for her: I think she imagines that she’s going to be a real activist now. And in these videos we’re just watching her struggle to make makeup tutorials into political statements, about causes she just found out about and barely understands.

But I also find that struggle endearing: she’s striving to be better, she’s trying to use her influence for good, with, I think it’s called "cringe-worthy results?" She’s been in the business of selling self-improvement for a while, but now she wants to do a make-over on her soul, like Cher in Clueless (who, incidentally, is also a privileged white woman). It’s easy to make fun of people like her, but we decided not to make it a total mockery. It’s a complex situation, right? She’s trying to get involved, but she doesn’t know what she’s doing. And in the last episode I think we see her realizing that she might not actually be offering any useful advice, or helping anyone, by telling them that if they have self-confidence and look good it’s going to protect them from real political and legislative threats to their safety.

Monica: She’s just like, "the show must go on!" And, just like everyone, she’s trying to find new meaning and purpose in what she’s doing. She’s thinking, "I have this audience I could educate about these things."

Cecilia: Monica’s direction really helped bring that out, for me, when I was trying to find the character in the performance. At first I was doing her in a really over-the-top, you know, like, "Hiiii Guys!", like, vocal fry, totally kind of bug-eyed and scary, which is actually—you do see a lot of that. But Monica was like, "This person should be someone that you like. You have sympathy for her, she’s really different, and she has all these different interests, but she’s basically someone that you might know, or meet at a party, that you have empathy for." I do feel empathy for her.

Monica: I thought it was really important that she have depth, and that those things came through. That it felt like she was an actual woman struggling with these things.

Cecilia: Basically what I’m saying is that Monica was like, "Try doing good acting. Like that, except with acting."

Are you worried about the NSA watching the series?

Cecilia: Um. No.

Monica: It’s more like what if the beauty industry NSA sees it. But, actually it’s been funny having interviews with beauty brands. I show them a few episodes and they are laughing and fully understanding what we are doing, but then they say, "This is so funny, it’s amazing, we could never do anything like this."

Cecilia: And we knew that. The reason that we didn’t really pursue doing this like for a brand or even a magazine per se, is because we wanted it to exist on its own in a modular way, which adds an uncanny tone. It looks and feels like a beauty vlog. But at the same time it’s dark, character-based comedy. And the intersection of those things is unusual: it’s just its own thing. Hopefully in an enticing way.

Did you want people to initially view it as a real beauty vlog?

Cecilia: I think that the primary way to read it is as comedy, at least that's our intention. But it's presented in a coy way. But if people read it as a beauty vlog, that’s awesome.

In an email, you’d mentioned wanting to work in a "venn diagram of beauty journalism, political commentary, and unhinged comedy." Could you talk more about how those ideas overlap in Le Balm?

Monica: We had so many conversations about how we wanted to put it out. And at the end of the day, we just said, "This is original content." It’s scripted, but it’s playing with meta-reality. There are heightened moments, but it could be real, on some level. Nothing we’re talking about is fantasy. And I think that realism is something both of us are interested in exploring, that essayistic quality. We’re both interested in creative work as a critical practice. But then again, this piece goes back to some of the things we know best. Performance for Cecilia, and for me, creating "content." Le Balm uses those two things to write an essay about this very specific sector of our culture.

Cecilia: Absolutely: the performance of branded content creation. Le Balm is an imitation of vlogger culture, and a tribute to it. It’s comedy about beauty content and it also is actual beauty content, in a way. It’s an expression of this weird moment we’re living through, rendered through this really simple and clear concept. It feels very conceptual to me in that way.

Monica: I think it asks its viewer to imply the depth, and to read into it. I think that’s the type of content that I’m most excited about.

Cecilia: Yeah. I’ve always really loved stuff that lives in a certain frame but does something different inside of that frame. The work that excites me the most lives in a certain context but plays with people’s expectations. A lot of the ideas in Le Balm are everywhere right now, and there’s been some amazing journalism recently about the strange relationship between contemporary politics and beauty culture. Of course, Le Balm isn’t journalism, even if it is kind of essayistic.

Monica: I think it is rooted in documenting a real phenomenon. Now, beauty is a really powerful category, much more powerful than fashion, because of its ability to create such personal change. Historically, beauty industries have always boomed during political turmoil because beauty is something you can control. Like Elizabeth Arden and all these brands being like, "Red lipstick is empowering!" We have an episode about that. Maybe there is an innate truth to it, because you feel better. It’s a real feeling.

Cecilia: It does seem like there’s so much emotion attached to that space now, so much public feeling around beauty, skincare, makeup. It’s like the final market where people believe buying the right products could actually make them better people. So the character represents something I think is a huge part of life in America and the developed world right now. The new form of aspirational luxury is self-improvement: you want your skin to look better, you want to spiritually be better, politically be better. I think this character wants to believe what we all want to believe, to some extent, that we can have control over our lives and that we can prevent chaos from enfolding us by focusing on self-improvement.

Monica: Beauty is definitely an exercise in control.

Will there be more Le Balm, either in this form or another, in the future?

Cecilia: I’m working on a pilot that’s an expansion of this world.

Monica: I think we also like the idea of using it as a discussion piece. That’s the thing I’m the most excited about, is seeing what people get out of it. It’s been really fun to hear the reactions of people from different backgrounds. There are these funny signifiers that trigger things for people.

Cecilia: Yeah, one of the things I’ve noticed in comedy is that people, when things hit too close to home, tend to be kind of repulsed, they’re like, "Ugh, I hate that character," if they identify too much. Whereas if you’re more distant from the character, you just laugh.

Deirdre Coyle is a writer and goth living in Brooklyn. Her work has appeared in Electric Literature, Lit Hub, The New Republic, Hobart, Joyland, and elsewhere. Find her on Twitter at @DeirdreKoala.

Joanna C. Valente is the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Xenos, and the editor of A Shadow Map: An Anthology by Survivors of Sexual Assault.

Read More

Ashely Adams

Jupiter

There is a storm older than the world (at the center of everything),

churning gods’ blood

(eating the flesh of their flesh).

Its daughters turned

into ice and rock under a jealous rain, bending

all the softness into metal.

(Don’t look).

This gale sings in hydrogen tongues

and swallows

swallows

swallows

Like this work? Donate to Ashely Adams.

Ashely Adams is an MFA candidate in nonfiction at the University of South Florida. Her work has appeared in Flyway, Heavy Feather Review, Fourth River, Anthropoid, Permafrost, OCCULUM and others. Her favorite astronomical body is the Galilean moon, Europa.