BY FREDDIE MOORE

I was in college the first time I drifted awake to find that I couldn’t move. I saw my roommates walking in and out of my room, turning on the TV, flickering the lights. They were shouting at me to get up, but my body felt like it was held down. There was no communicating with it. I wanted to shout back, but I couldn't. I wasn’t able to speak.

When my body came back to me, and I was able to move my fingers and lift my weight, I found the room was empty. The door was locked from the inside. I was sure of what I had seen, but none of it was real.

Sleep paralysis made me feel like I was losing it, even when I found out what was happening to me. The paralytic state most experience to keep from responding physically to dreams—“muscle atonia”—neglects to turn off for those who experience sleep paralysis. It is the opposite of sleepwalking. The sleeper comes to awareness before the rest of their body, stuck somewhere between REM and reality, often hallucinating with the part of their mind that can dream. And because they can’t move, it’s terrifying. It feels like a momentary death—being separated from your body. It’s the kind of thing that can make you believe in spirits and worry you might never come out of it.

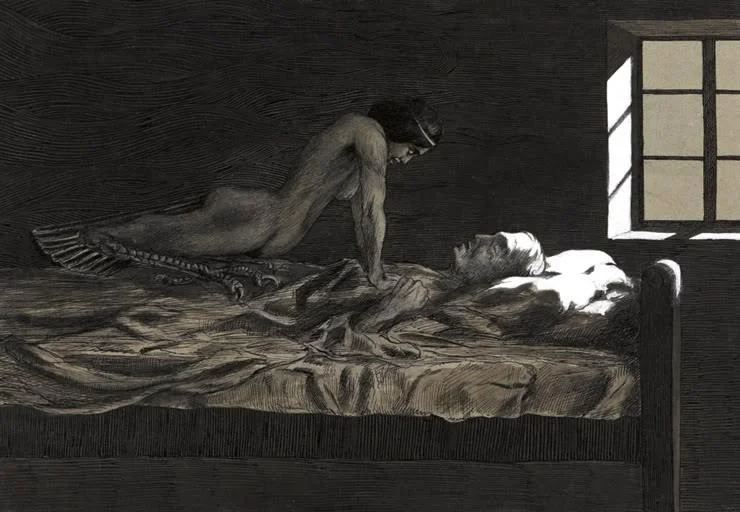

Across cultures, some explain the disorder with supernatural forces, like demons, ghosts, and aliens. In Newfoundland, Canada, lore dictates that sleepers who experience paralysis are visited by an old hag who suffocates victims as she sits over them. It’s like the famous image in Fuseli's 1781 painting, “The Nightmare.” The most common phrase for sleep paralysis in Mexico translates to “a dead body climbed on top of me,” and in China, sleep paralysis is thought of as “ghost oppression” and is often called bei gui ya: to be “held by a ghost.”

Even if you don’t believe in spirits—or the soul as something separate from the body—sleep paralysis can make you think twice. I had spent four years convincing myself that ghosts didn’t exist when it started happening. The ghost I worried about was Michael. He was the quiet, kind man who rented the basement apartment from my family and had been killed during a domestic dispute while we were home. Our house was old, it made noises when it was empty. It made noises after Michael died. I had moved away to college six months after it had happened and learned to reason with myself, but sleep paralysis made everything uncertain again.

Sleep paralysis had its way of coming to me when I was stressed or hadn’t been sleeping much. When it happened again, I was staying at my friend’s house to avoid a bed bug infestation at my home in Brooklyn. I was anxious every night that I would wake up covered in bites. I wasn’t sleeping well. I had drifted off while watching TV and woke up to the phone ringing. When I tried to get it, I was held back by the same heaviness I had experienced the first time. I couldn’t move. The TV was dead. The phone kept ringing. I tried shouting, saying anything, even though I knew why nothing was coming out. When I could move again, the ringing stopped and everything was slightly out of place from the way I had seen it. The TV was still on, and my friend was on the chair next to me, flipping through channels. “You were making weird moaning noises,” she told me, without taking her eyes off the screen.

The lights, the phone, the questionable TV stuff—each thing I hallucinated had nothing to do with Michael. But it felt like losing control.

To avoid having it happen again, I tried a number of things. I stopped sleeping on my back. I tried keeping a regular sleeping schedule and going to yoga. I tried not to think about Michael. It wasn’t logical, but my worst fear then, as it had been for years, was that I would hallucinate and see him. He would be the dead person sitting over me.

Sometimes, out at parties, after a few drinks, I would meet someone else who had experienced it. Sleep paralysis isn’t rare—roughly 7.6% of the general population and 28.3% of students experience at least one episode. I remember meeting this one guy who said the worst thing for him was the feeling that he was floating away from his body. He was so animated when he talked about it, like we were bonding over having the same awful ex.

Some studies have shown that suffering a traumatic life event can increase the likelihood of sleep paralysis. After Michael died, there was a long time when I couldn’t sleep because any creak in the floor—or noise, for that matter—would send my heart up through my chest to my throat like a wild thing that didn’t answer to anything. I was jolty. I would reach for sharp things when I worried I wasn’t alone in the house. It made me feel like a victim and I felt guilty for feeling that way. Nobody took my life away from me.

At times, these moments were more unsettling than sleep paralysis. It’s different to be conscious when you’re thoughts separate from reality. I would tell myself to calm down, but my heart would go on jumping, ignoring commands.

It took years to finally convince myself out of that fear. There are so many factors that can lead to sleep paralysis: lack of sleep, sleep problems (from narcolepsy to leg cramps), stress, depression, anxiety, or even something as simple as choosing to sleep on your back. It’s possible that Michael’s death had nothing to do with my paralytic states, but I like seeing the story that way. It keeps him alive.

For a while after I stopped getting sleep paralysis—who knows why it stopped—I would imagine what it’d be like to drift off onto my back again and wake up frozen to find Michael sitting over me. There’s no getting over it—sometimes I still wonder. Would he try crushing my breath away?

I don’t think so. My ghost would be the same soft-spoken guy he was when he was alive. He would flicker the lights and tell me to get up when I’m ready.

Freddie Moore is an ice skating instructor who grew up Brooklyn, NY. Her writing has appeared in Electric Literature, LitReactor and The Huffington Post. She left her heart at The Airship. Follow her on Twitter.