BY KAVITA DAS

Last fall, I attended Becoming Another: The Power of Masks, an exhibit at the Rubin Museum of Art, a museum in New York City dedicated to Himalayan art and culture. As a child, I collected masks and loved how they served as portals to imaginary identities and faraway places. This exhibit fit that bill, "illuminat(ing) the common threads and distinct differences in mask traditions from Northern India, Nepal, Bhutan, Tibet, Mongolia, Siberia, Japan, and the North-West Coast tribes of North America."

I was particularly intrigued by the exhibit’s focus on how masks "speak to the human impulse to transform one’s identity"—to become another. Beyond merely displaying masks from different countries, the exhibit highlights how they are used as part of theatrical costumes, for religious rituals, and in spiritual shamanistic practices.

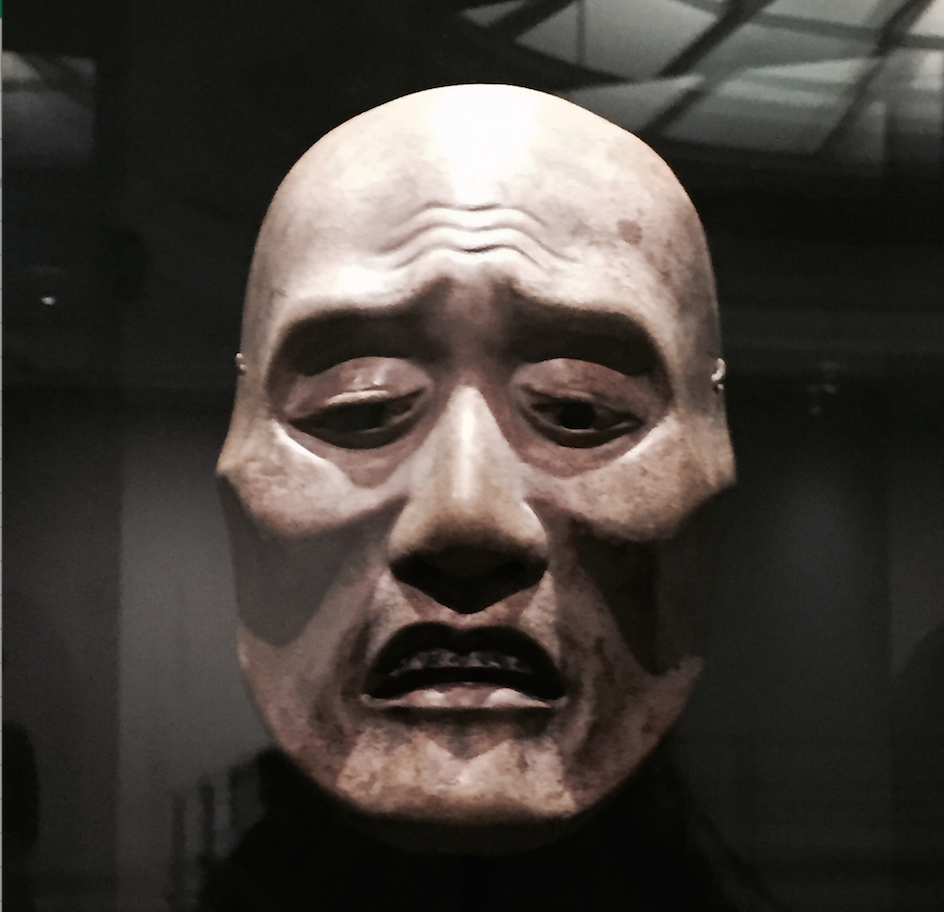

I walked through the exhibit, pausing to admire the beauty and power of certain masks, discovering cultural rituals I had never known. And then my eyes locked on a stark white mask across the room that conveyed a face in a paroxysm of pain and suffering. I felt myself drawn to it. When I finally stood before it, I was transfixed.

My curiosity about it finally allowed me to pull my eyes away to read its description. It was a theatrical mask used in Japanese Noh theater, dating back to the Edo period (1615-1868), and it depicted a Yase-otoko. "Yase-otoko is a general representation of a suffering ghost that abides in hell." It also included a physical description. "His disposition has nearly turned his emaciated body into a skeleton with a bloodless-looking face. His eyes are sunken deep in their sockets, his cheekbones are pronounced, and the sharp, downturned corners of his mouth express the torture he is going through."

But if the physical appearance of the Yase-otoko arrested me, the reasons for the ghost’s suffering shocked me: "punished either for having killed human beings or animals or for being obsessed with being treated unfairly during his life." The first part of the reasoning made sound sense but the second confounded me. How could one’s obsession with being treated unfairly during one’s life be equated with the suffering brought on by killing human beings and animals? I stared at the description for several minutes hoping I had read it wrong. I wrestled with this question on my walk home, and for several hours afterward.

Beyond the puzzling explanation of the Yase-otoko was the realization that in some small but irrefutable way, I recognized myself in it. Ironically, what had drawn me to this 17th century mask of a suffering ghost was my experience with a very twenty-first century phenomenon with an eerily similar moniker; ghosting, the practice of pre-emptively dropping all communication and interaction with a lover or close friend without any prior warning. Over the last few years, I’ve had two close friends, one who I opened my home to and another who opened their home to me during a moment of need, disappear into the virtual and real-life ether. Both of these friendships were now over and yet their hold on me was not. I found myself alternately pondering if and how I might have wronged them and resenting them for ghosting me.

But why should a person obsessed with being treated unfairly suffer such a terrible fate? Perhaps people who remain fixated on their unfair treatment are, in a sense, robbing themselves of their own life. Instead of acknowledging the unfairness and moving on, they become paralyzed, hashing and rehashing it, without hope of resolution. While there is a stark ethical contrast between someone who unleashes their demons on others and someone who is struggling with their own private demons, the Yase-otoko symbolizes the perils of bitterness, regardless of the reasons behind it.

Maya Angelou, one of the writers who I most admire and who faced much adversity on her path to becoming a writer, said, "Bitterness is like a cancer. It eats upon the host." As we move through life it seems inevitable that we’ll be wounded along the journey—whether it’s heartbreak from an unrequited love or the betrayal of a close friend or a devaluing work experience. These wounds are how we know we’ve lived and survived. But bitterness is a sign that life has moved on, while we haven’t. Blinded by the mask of bitterness, we continue to cling with both hands to old grievances. Removing this mask makes us vulnerable while also giving us a chance to extend ourselves towards possible joys that we can now, once again, perceive.

Coming face to face with the Yase-otoko forced me to confront the haunting spirit of bitterness with which these friendships had left me burdened and to decide whether I wanted to remain embroiled, or let go, by removing the mask of bitterness. Letting go would involve accepting not only that the friendships were over, which was difficult, but also accepting the lack of resolution, which was surprisingly even harder for me. Once I let go though, I was able to see with clarity the cherished friends, with whom I celebrate victories and commiserate sorrows, the ones who I’ve been leaning on and who’ve been leaning on me in ways that are often unspoken but never unrecognized. Most importantly, removing the mask of bitterness I was forced to wear because of a few toxic friendships has allowed me to return to focusing on becoming a better person, and consequently a better friend.

Kavita Das worked in the social change sector for fifteen years on issues ranging from homelessness to public health disparities to most recently, racial justice and now focuses on writing about culture, race, social change, feminism, and their intersections. She's a contributor to NBC News Asian America, The Rumpus, and The Aerogram and her work has been published in VIDA, McSweeney's, The Atlantic, Apogee Journal, Guernica, xoJane, The Margins, Quartz, The Feminist Wire, Colorlines, The Sun, and elsewhere. You can find her full portfolio here.