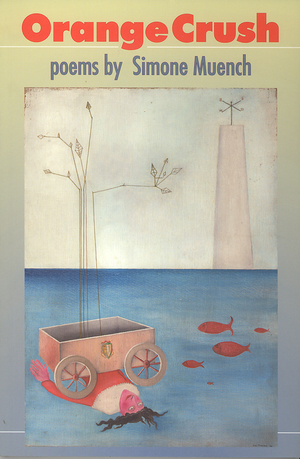

ORANGE CRUSH

Simone Muench

ISBN-13: 978-1932511796

Sarabande Books

88 p.

Reviewed by Lisa A. Flowers

Take the landscape evoked in Randy Newman’s In Germany Before the War, the strangling scene in Strangers on a Train, a seaside scattering of rinds and corsages, and corsets and formal wear defaulting to corsets and burial wear and you come close to approaching the general soul of Simone Muench’s Orange Crush, a book where 17th century English prostitutes, murder ballads, and early Springsteenish characters fall into slasher films like cherry blossoms shaken from a vengeful o'erhanging firmament. Open Crush and a browned valentine or a phone number scrawled last week on a bar napkin (both belonging to girls since unnaturally deceased) might fall out. The book debuts in bloated summer, in Wisconsin Death Trip country, where “trouble comes,” bringing

Chalklines in bloody bedrooms

Clouds

Agitating the cows, their thick ruminant bodies

Clogging up the riverbeds ...

Children dying of oddities

The small-town doctor could not name …

You Were Long Days and I Was Tiger Lined seems to present another atrocity, perhaps one related to the evil of slavery, going on in the same town:

Weather me better master

Wind can carry a whip but how

Can a dead girl

Swerve into flight and miss the sky altogether

In these lines, and throughout the book, is the panic of souls violently killed, beating their huge new wings frantically against panes like trapped insects. And Muench, whose name to the printed eye suggests the sinuous and nightmarish waterfront of that other Munch and his The Scream, is adept at transitioning between poems with the same kind of wavy disorientation. Quite unexpectedly, we’re in the hospital undergoing cancer treatment with Count Backwards to a Future With You in it and Where Your Body Rests (the latter dedicated to “the woman who said I lacked duende while undergoing chemo and radiation”) where IV’s hematomas bloom in tandem with sexual imagery worthy of Georgia O' Keefe’s flowers:

Nothing separates us

From the sun’s luminous text,

The way words enter skin in fire spirals

Lifting the room into a red vivarium ...

At other times, some monstrous apparition, “long and shedding its scabbed horizon” will dart suddenly through the text. And Muench can shift into 1930s crime film noir with the abruptness of a gunshot. The first line of the short poem Frame 6

The Colt sang once, parting

Your pitch-dark hair.

is an image that exists in three colors: ebony, seeping crimson, and the glaring white of shattered cranial bones.

All Orange Crush’s tendrils weave from its godhead the Orange Girl Suites, dedicated to Susannah Chase. Muench can show us what it's like to be thrown into the middle of a crime, reeling in a panicked psychobabble of random, garbled last words:

When he killed her he said listen

…He said windowsill

He said stone

While alive she replied

Oilslick, doorjam…

The poems thicken with what they describe, gruel-like:

A man folds a girl up in newspaper, her wet hair a string of taffy....

In one version

She folds up

Like a fan, her songs pleated

Gills panting underwater.

In another, she fashions

The wires of her earrings

Into antennae, transmitting her story across the harbor

Her taffeta dress sliding toward the lighthouse without her...

Skin gathering the Baltic’s debris,

An intersection of earrings and quiet, wrists and rope.

These images are terrible in their calm, austere dignity. Muench has hit upon reality at its most awful and minimally articulated; drawn her body of work up to the dignity of its full height: the height of the unspeakable and its consequences, which are the “disease of a body syntactically disarranged/limbs and hair webbed with algae.”On the other hand, “no one can be reached/in this city of correct syntax/where the water deposits its marginalia” and by using words like zigzagging film editing techniques, Muench can conjecture powerhouse lines out of Japanese arthouse horror, suggesting a hundred mirrored spider eyes by which a girl dismembered in a love hotel might be

Looking out of herself

Through so many stabmarks, eye slits

So many voyeured holes

Camera flash on her mouth

Her belly, a billfold

Zoom

To navel

Vortex of torso

Vertigo

Suite 6 is a stunning poem that distinctly evokes Roethke’s The Song:

A girl is running, is bleeding ...

The railroad a rusted zipper

Fusing Louisiana and Arkansas ...

Moving through the woods

In a thin white suture ...

[running] through rain until she is rain

The “Orange Girl cast” (literally, the cast of the book) are Muench’s own female friends (and other poets) who are thanked/named in the appendix. They are modeled on many archetypes, including those girls “born to unzip men’s breath.” “(“You can’t fold her up inside a cocktail napkin,” Femme Fatale reminds us/chastises us,“she will not rinse.”) Later, the same Cleopatra “imprisons pharaohs in her spine”: a magnificently seductive line that recalls Anne Sexton’s “for I pray that Joy will unbend from her stone back and that the snakes will heat up her vertebrae” from O Ye Tongues. At one poem's end, a protagonist gnaws her prey idly, a lioness, while, "through the slats of her magnolia latticed teeth"… like a distracted child’s toy into the sea… "a dollhead floats free of I do."

In The Apriary, a kind of coming of age poem, two young girls lounge in a sunlit attic, reading Keats, whispering to each other through “the veils of glamorous biblical women, loaded up on blossom.”The Matryoshka is a splintered semblance of Frederic Leighton’s Flaming June in a prose-poem:

Sunlight buzzes your windows as you crack a kaleidoscope in half, searching for a photograph of your mother before disease split her face into reflection and recollection. When you slide to the floor, your dress spreads volcanic, an orange silk corona…

There is sexually-deprecating humor dotted here and there:

Dialing his large white teeth

With her tanager-tongue

She laments

“Where art my thigh..."

And little spook-stories:

Ask the strange man on adrenaline reserves-

Would a maniac roam around a cemetery

Wearing one black glove?

Muench's work winds itself into its own ribbons of brilliant reds and oranges and blues, whilst simultaneously unrolling bandages backwards into the mummy it never wanted the victims it eulogizes and empowers so beautifully to become. “I will chew your light into miniature suns/and when the time comes to bury you, I will say undo. Undone” are the lines that conclude the book. Or, to quote Kathy Acker via one of Orange Crush's epigraphs, “All of us girls have been dead for so long/But we’re not going to be anymore.”

_________________________________________________________________

Lisa A. Flowers is a poet, critic, vocalist, the founding editor of Vulgar Marsala Press, the reviews editor for Tarpaulin Sky Press, and the author of diatomhero: religious poems. Her work has appeared in The Collagist, The THEPoetry, Entropy, and other magazines and online journals. Raised in Los Angeles and Portland, OR, she now resides in the rugged terrain above Boulder, Colorado. Visit her here or here.