BY PATRICIA ANN GRISAFI

I always wondered why the most famous contemporary exorcism story took such liberties with its main character. In William Peter Blatty’s 1971 novel The Exorcist and its 1973 film adaption, a twelve year old girl becomes possessed by a demon. However, in the real-life incident in which Blatty based his story, it was a young boy who allegedly suffered from possession and had to undergo multiple exorcisms. In the late 1940s, “Roland Doe” or “Robbie Manheim” the young boy’s pseudonyms (yes, many people have tried to pinpoint his identity without luck), began exhibiting disturbing behavior shortly after the death of his aunt. He was violent and profane; he had uncommon strength. Objects moved around the house when he was nearby, and strange noises were heard. Injuries appeared on his body.

However, in The Exorcist, “Roland Doe” becomes Regan, setting off what would become a popular trend in the possession sub-genre: a female victim. Why do movies about demonic possession overwhelmingly place young women in the position of afflicted victim? What does this strategy tell us about the representation of women’s sexuality, agency, and power in contemporary horror film?

Horror is a genre that is simultaneously seen as conservative and radical. Often, despite unmitigated gore and disturbing behavior, order is restored, the final girl survives, the monster is bested. Even the occasional unhappy surprise at the end - the killer’s hand twitches, an eyeball shoots open, a door slams shut on its own accord - has a comforting predictability.

But sometimes, a horror film concludes on ambiguity, the loss of boundaries; there is no neat reinstatement of order or tradition. Particularly in the possession sub-genre, this kind of uncertainty triumphs: is the victim cured or is she still possessed? Can she be possessed again in the future? What caused the possession to happen in the first place?

The contemporary possession and exorcism narrative as we know it begins with The Exorcist and Malachi Martin’s salacious 1976 book Hostage to the Devil, which helped reenergize America’s flagging interest in demonic possession. These two cultural products not only reinvigorated America’s interest in demonology but also spoke to a sense of America’s sexual politics at the time. The sexual revolution, postwar counterculture, and Vatican II’s secularization of the Catholic Church made more traditional morals and behaviors seem outdated.

Post 9/11, the possession sub-genre continues to be unflaggingly popular. Over the last fifteen years, at least thirty-one possession-themed films have been released. Most feature a young woman at the center of the possession, writhing in her own filth, grasping at her breasts, spitting, cursing, and taunting. Alongside her is a man - a priest, rabbi, spiritual healer, or family member - and inside her is a demon, usually gendered as male and often portrayed as a seductive lover. In these films, two men essentially battle for the body and soul of a woman - quite the romantic cliche.

The possession sub-genre has always focused on female sexual power and how such power can threaten the status quo. Here are a few movies, both classic and contemporary, that make this connection in intriguing ways.

The Exorcist (1973)

Image via Blumhouse

One of the most influential films ever, The Exorcist helped create myriad conventions in the demonic possession sub-genre - including the figure of the young girl writhing, moaning, bleeding, and masturbating while priests frantically try to restore order and save her soul.

While many critics interpret The Exorcist as a classic film about the clash between good and evil, we can also look at the movie as a coming of age story featuring a young woman going through a more horrific-than-usual puberty. Regan’s gutter mouth and the plethora of bodily fluids splashing around place her firmly in the fraught, embodied space of the female grotesque. Additionally, taking place during the women’s liberation movement, The Exorcist seems to suggest that in a world of working, single mothers the devil will find his kicks.

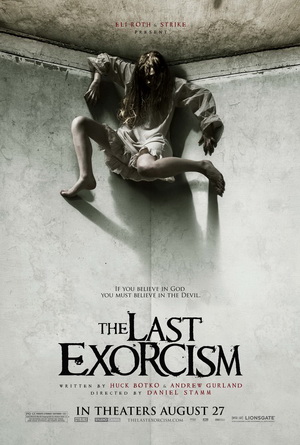

The Last Exorcism (2010)

Image via Wikipedia

Convinced that demonic possession isn’t real, Reverend Cotton Marcus gives placebo exorcisms to believers for what he considers psychological benefits. When Marcus is called to investigate Nell, a young girl living in rural isolation with her father and brother, he finds a simple teenager, awkward and effusive, unsure of herself and embarrassed by the fuss. There’s no reason to believe anything is supernaturally wrong, but Marcus performs the sham exorcism anyway and placates the family.

Things start to get out of control when Nell shows up at Marcus’ motel and molests a camera woman. Nell’s behavior continues to deteriorate; she becomes violent and sexual, making lewd comments and gestures and murdering a cat. After discovering that Nell is pregnant, Marcus begins to think that she is being sexually abused by her father and that he has stumbled on a case of incest.

The Last Exorcism is a movie about faith, but it is also a narrative about the power of fantasy, the dangers of exploitation, and how young women coming of age are simultaneously posited as helpless victims and powerful sexual creatures.

Lovely Molly (2012)

Image via Wikipedia

Molly, a recovering heroin addict, and her new husband move into her childhood home. Shortly thereafter, he has to hit the road for work. Left alone for days, Molly begins to experience strange phenomenon, including an invisible presence urging her to open the closet in her old bedroom. When her husband returns home, he finds Molly naked and crouched in the corner, cowering like an animal or child who has been beaten.

As the film progresses, it appears that Molly’s demons are caused by childhood sexual and physical abuse, but the line between reality and the supernatural remains blurred. However, the real horror comes from watching Molly retreat into a feral state as she stalks the house naked, her body a threat and weapon. Has she relapsed? Is she possessed by the same demon that possessed her father? Or is she traumatized by living in the house where she was victimized as a child?

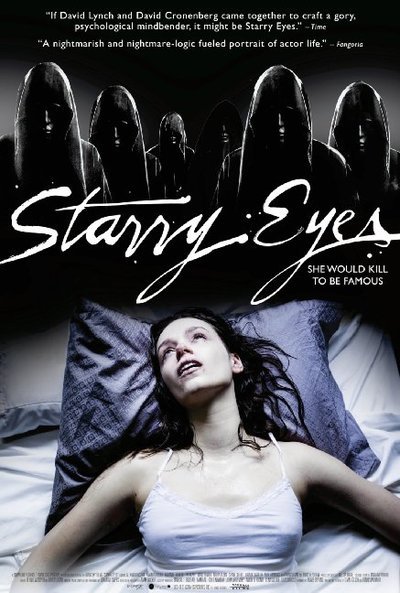

Starry Eyes (2014)

Image via Roger Ebert

When Sarah first appears, she’s working in a Hooters-esque restaurant, tottering on high heels and squeezed into spandex leggings and a tight T-shirt. Soon after her shift, she has a disastrous script reading and privately rips out her hair in chunks, making her emotional instability manifest. As a fledgling actress, Sarah’s more flailing than flying, so when she gets a chance to audition for a role in a horror movie, she really commits, writhing on the floor, ripping out more hair, and screaming like a woman, well…possessed.

In this story of ambition, insecurity, and transformation, Sarah is haunted by the legends of old Hollywood as they gaze at her from the walls of her bedroom. It’s clear Sarah has internalized the myth of the “big break” and the worth of a woman’s body in the Hollywood economy; in an update on the classic casting couch scene, she effectively sells her soul via a blow job.

Starry Eyes plays with the tensions between glamour and disease, sex and power, and authenticity and artifice. It’s not a traditional possession film, but Sarah certainly undergoes a disturbing transformation on the way to making her movie star fantasies come true.

The Neon Demon (2016)

Image via The Telegraph

Jesse is that rare creature who stops people in their tracks with her transcendent beauty. She is an ingenue, a blank slate, and a threat. Older models want to devour her; friends and lovers want to possess her. There’s a sense that she’s a helpless waif in the menacing woods of the Los Angeles fashion world. But as Jesse comes into her sexuality and discovers her power, she becomes palpably dangerous.

The crowd she hangs with is both sycophantic, sinister, and deeply miserable. The models have all modified their bodies with excessive plastic surgery and take pleasure in others’ failures. In one of the most controversial scenes in recent years, Jena Malone’s dead-eyed make-up artist, Ruby, takes symbolic possession of Jesse by having sex with a corpse she has made up to look like her.

So who is the demon in this gorgeous, slick, and lurid film? And who becomes possessed? While you won’t find the power of Christ compelling anyone, Jesse comes across as both victim and demon, seduced by the bright lights and then possessed by her own narcissism.

Patricia Grisafi, PhD, is an English instructor and freelance writer. Her work has appeared in Bitch, Bustle, The Gloss, and Rogue Agent. She is passionate about poetry, pitbull rescue, cursed objects, and designer sunglasses.