BY TRISTA EDWARDS

Salem is a city that stands as a testament to the power of language. Witch has become trendy. Contemporary witchcraft is booming. Women and men alike are reclaiming this word, this title, with surmounting pleasure and empowerment. Many will argue for the witch being the icon of fourth wave feminism. It is sometimes hard to discern why or how this trend has become so prevalent. Perhaps in a world that currently feels it is tumbling a gyre of chaos, we turn to a figure that illustrates control—the image of woman who can conjure and create a world around her, who uses her natural resources and knowledge to manifest and enact change. Although there seems to be some quibbling about those who practice the craft with serious religious study and those who have become attracted recently by perhaps the more consumerist, fashionable, and arguably less devout claim to witchery. Despite these equivocations, witch is in.

In all this excitement, we can often forget that at one time the very utterance of the word witch was enough to prove your alliance with the devil, for neck to meet the noose. The word summoned up all connotations of evil, subversion, and direct defiance of Christianity. It become an easy way to condemn others, particularly women, for possessing knowledge, acting as sovereign within the larger community, culling and applying natural resources to heal others, for their sexuality, for their bodies—for the very fact they were not men and would not submit to the expectations of their sex.

I recently visited Salem with the authority of language in mind. I couldn’t stop thinking about it, the word itself, witch. I indulged a bit in the inane tourists traps—the shops of mass-produced kitsch and the less than historically motivated museums—but what I was really seeking was some kind of ingenuous record of the past, some kind of reverence for the horrors that occurred over 300 hundred years ago in which over twenty people died (either by execution or when awaiting trial while in prison) because they were cast as a witch.

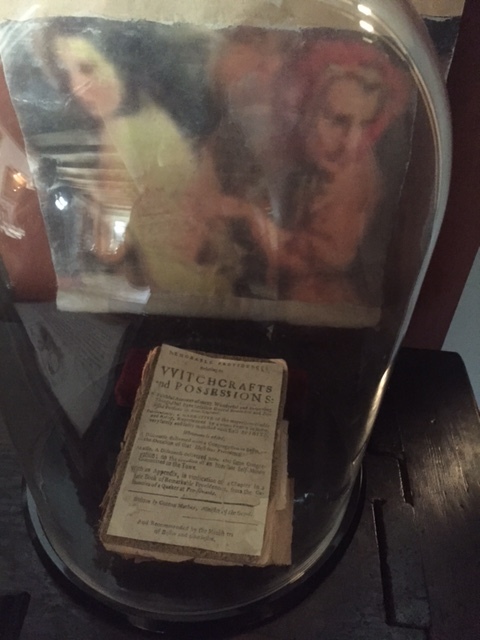

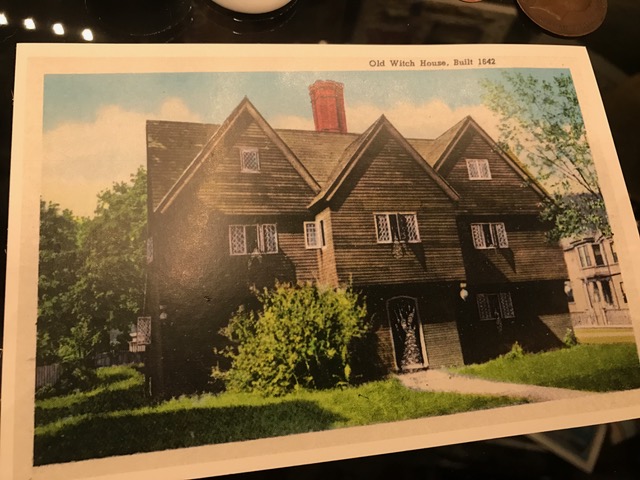

One structure still remains standing in Salem with direct ties to the Salem witch trails of 1692—the house of Jonathon Corwin, otherwise known as The Witch House. Corwin was one of the magistrates called into Salem to conduct preliminary queries into the acquisitions of witchcraft. He, and other magistrates, collected testimony from the first three women charged with witchcraft—Tituba, Sarah Good, and Sarah Osborne. Over the course of the hearings, Corwin issued several arrest warrants. Detailed records of his role and attitude toward the trails are scarce due to insufficient documentation involving Corwin. The Witch House website, however, claims he served on the Court of Oyer and Terminer which ultimately sent nineteen people to the gallows.

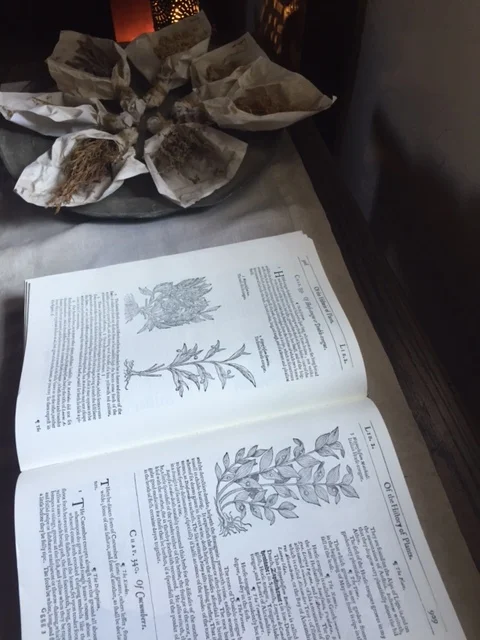

To walk through the Witch House is to get a sense of the Spartan quality of life even thought the Corwins were considered among the wealthy elite at the time. What struck me the most walking through the house were numerous artifacts of a homeopathic nature, particularly that of childbirth.

Such artifacts included:

Groaning Beer—ale brewed and served to a woman while she was in delivery with the hope of bolstering her for the act of childbirth.

Remedies to enable conception by cleansing a woman’s body and her organs with dandelion roots or burdock to create a “pure-nest.”

Notes on consuming raspberry leaf and yarrow to strengthen and tone the uterus.

All artifacts stand as evidence of the medical practice of the times yet I couldn’t help but think of the so-called “lay healers,” or midwives of the middle ages who participated in similar forms of medicine and then were burned for it. Although the climate and surmounting events that lead to the 1692 Salem witch trials perhaps differ circumstantially from the centuries of persecution in Europe, there is the common thread of the condemning power of language.

The Witch House as a structure in and of itself is hauntingly beautiful. It is dark and gothic with vast brick fireplaces hung with herbs. The windows have glazing bars and there are immense mint bushes crowding the back entrance emitting waves calming aromatics. Inside, the wood floor boards and narrow staircases creak and give with every step. The house is cool and enjoys many shadowy corners.

It is one of the few places to turn to in Salem that stands to provide a glimpse into the past, at least as it looked. Other commemorative sites include the Salem Witch Trials Memorial, which resides next to the Old Burying Point. Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel dedicated the memorial in August 1992 as part of the Salem Witch Trials TerCentenary. It consists of 20 granite benches inscribed with the name of the accused and date of their execution.

Additionally, there is the Salem Village Witchcraft Victims' Memorial located about half an hour north in the town of Danvers, originally called Salem Village. This memorial marks the site of the original meetinghouse in which the trials were held.

There is a large stone monument inscribed with some of the victims’ last words:

"I am an innocent person. I never had to do with witchcraft since I was born. I am a Gosple woman." Martha Cory

"Amen. Amen. A false tongue will never make a guilty person." Susannah Martin

"The Magistrates, Ministers, Jewries, and all the People in general, being so much inraged and incensed against us by the Delusion of the Devil, which we can term no other, by reason we know in our own Consciences, we are all Innocent Persons." John Procter, Sr.

Yet, the reclaiming of witch is also an inspiring force throughout the city. There are Salem women and men who genuinely practice a craft, provide services, and flourish as makers for something that would once have taken them to the gallows. There are herbalists, occult shop owners, tarot readers, and crafters. They exist beyond a trend. They are the kinetic history that flourishes under the past’s shadow of violence.

There are several Salem shops to visit to feel the power and pride of creating under the banner of word that was once held the weight of destruction:

I firmly believe that whatever force turned you to the witch, the resurgence of this particular kind of feminine power is indispensable.

Trista Edwards is a poet, traveller, crafter, creator, mermaid, and an old soul. She currently serves as Co-Director of Kraken, an independent poetry reading series in Denton, Texas. Her poems and reviews are published or forthcoming in The Journal, Mid-American Review, 32 Poems, American Literary Review, Stirring: A Literary Collection, Birmingham Poetry Review, The Rumpus, Sout’wester, Moon City Review, and more. She recently edited an anthology, Till the Tide: An Anthology of Mermaid Poetry (2015).