BY TRISTA EDWARDS

This piece is part of the Relationship Issue. Read more here.

I’ve always had an attraction to darkness. When I was a child, my family lived beside the town cemetery for several years. The cemetery butted up against our backyard. I was forever wandering among the dead. I would sneak out past our property to traipse amid the first couple rows of graves but close enough that, if my mom called my name, I would hear and have plenty of time to run back into view.

I was hardly frightened. I would collect pebbles and leaves in my sand pail and poke the snake holes with sticks. The most intriguing and curious part of my visits was stumbling on the headstones adorned with pennies. Who left these and why, I often wondered? Sometimes I would return to a headstone to find the pennies gone. Sometimes they were replaced with a neat row of rocks of varied sizes or they had grown into nickels or dimes. At the tender age of seven or eight, I was unfamiliar with the assorted rituals and superstitions that evolved leaving pennies on graves—payment for the ferryman, soliciting wishes from the dead, a sign of rank and/or personal association to a deceased member of the military. The only explanation my young mind could fathom was ghosts left the coins for reasons that I wasn’t meant to understand.

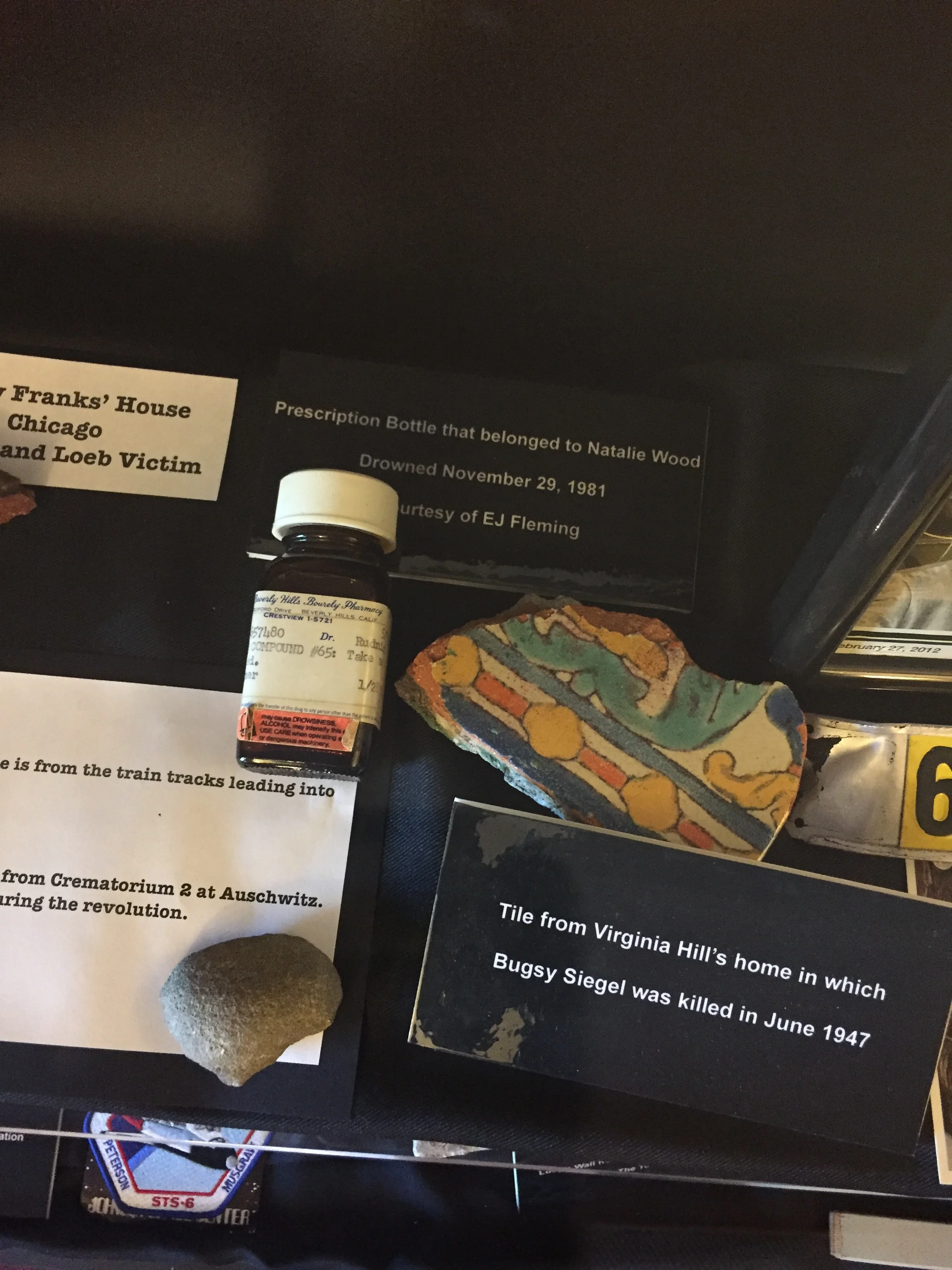

Nataile Wood's prescription pill bottle

I now admit with ignominy that I snitched a penny or two, added them to my pail’s stew of mud, twigs, rocks, and bird feathers that I had collected. The contents of pail never met any immediate objective or clear intention to their usage but I collected them nonetheless hoping that the purpose of my little curiosities would reveal itself in time. I took the pennies because I knew I shouldn’t. I was a quiet, introverted child who was not particularly prone to acts of rebellion or rule breaking but there was some kind of mystery in the pennies that I had to have them.

I thought about this childhood fascination with graveyards and my collecting of the dead’s pennies on a recent trip to Los Angeles when I partook in the Dearly Departed Tour. The tour’s main office is headquartered in Hollywood and, as their website states, remains Tinseltown’s "authoritative celebrity death source." My fiancé, Aaron, and I were in town visiting family and my future in-laws booked the tour as part of Aaron’s birthday celebration. I couldn’t have been more delighted—it may as well have been my own birthday. Yet, upon entering into the office I began to feel immediately ambivalent. We arrived early and the owner invited us to wander around the shop, which doubled as a museum, and explore his collection of tokens from Hollywood icons’ troubled lives and last moments.

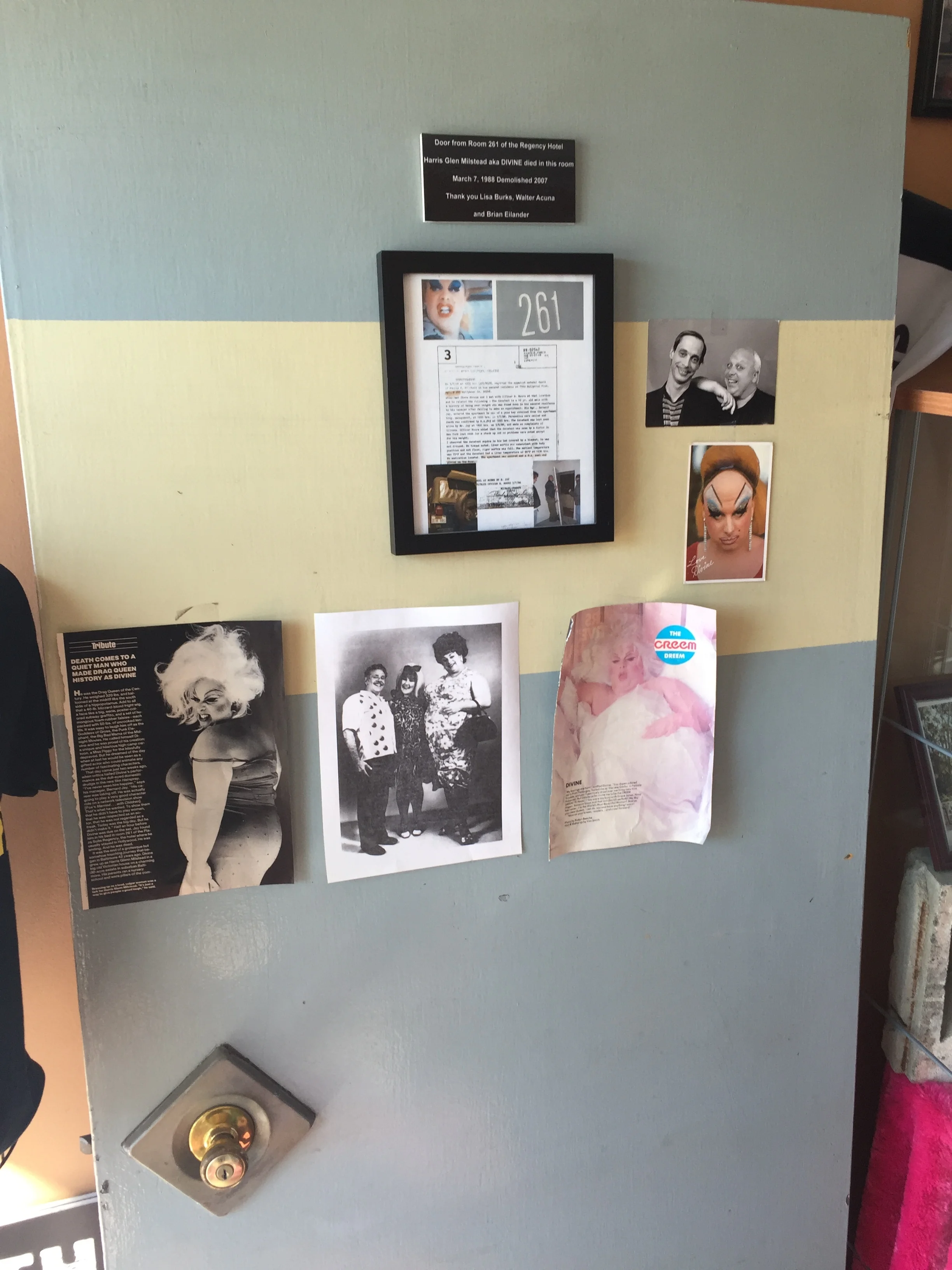

Devine's hotel room door

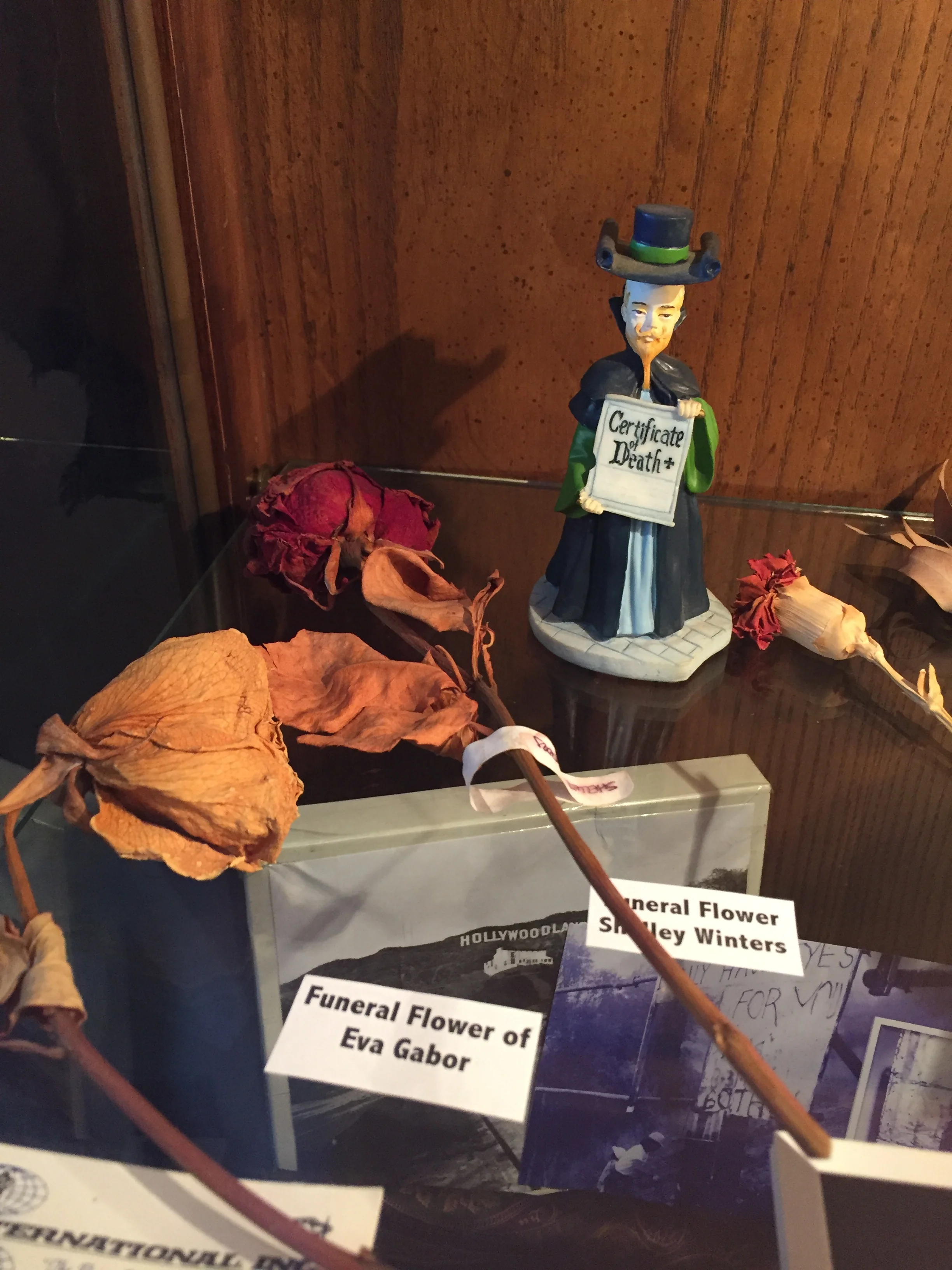

There was prescription pill bottle that belonged to Natalie Wood. Dried and preserved funeral flowers from Eva Gabor and Shelley Winters. The mint green hotel door from room 261 of the Regency Hotel where performer, singer, and drag queen Divine died of an enlarged heart. I felt conflicted. Conflicted by my exhilaration for the impending tour and the museum’s haunting artifacts and, yet, simultaneously distressed by the fetishization (both my own and owner’s) of relics of tragedy. My internal struggle grew when the owner of the shop approached me and gleefully pointed to a barren tree branch hung on the wall.

"You see that!" He gestured to the thin branch that measured roughly three feet long. "I took that branch from a tree that was near site where Paul Walker died in a fiery car crash! I saw it hanging there not far from the crash and I had to have it!" Then he gestured to a somewhat pixelated photo framed next to the branch. The photo standing as proof by showcasing the tree as it still possessed the branch before he plucked it to add to his shop of Hollywood curio. His childlike elation for snagging a branch from a tree that was in the proximity of a celebrity death was curious, to say the least. The exact tree itself was not directly connected to the death at all. It was just…close enough. Close enough to death’s aura to have meaning. I sympathized with his sentiment—he had to have it.

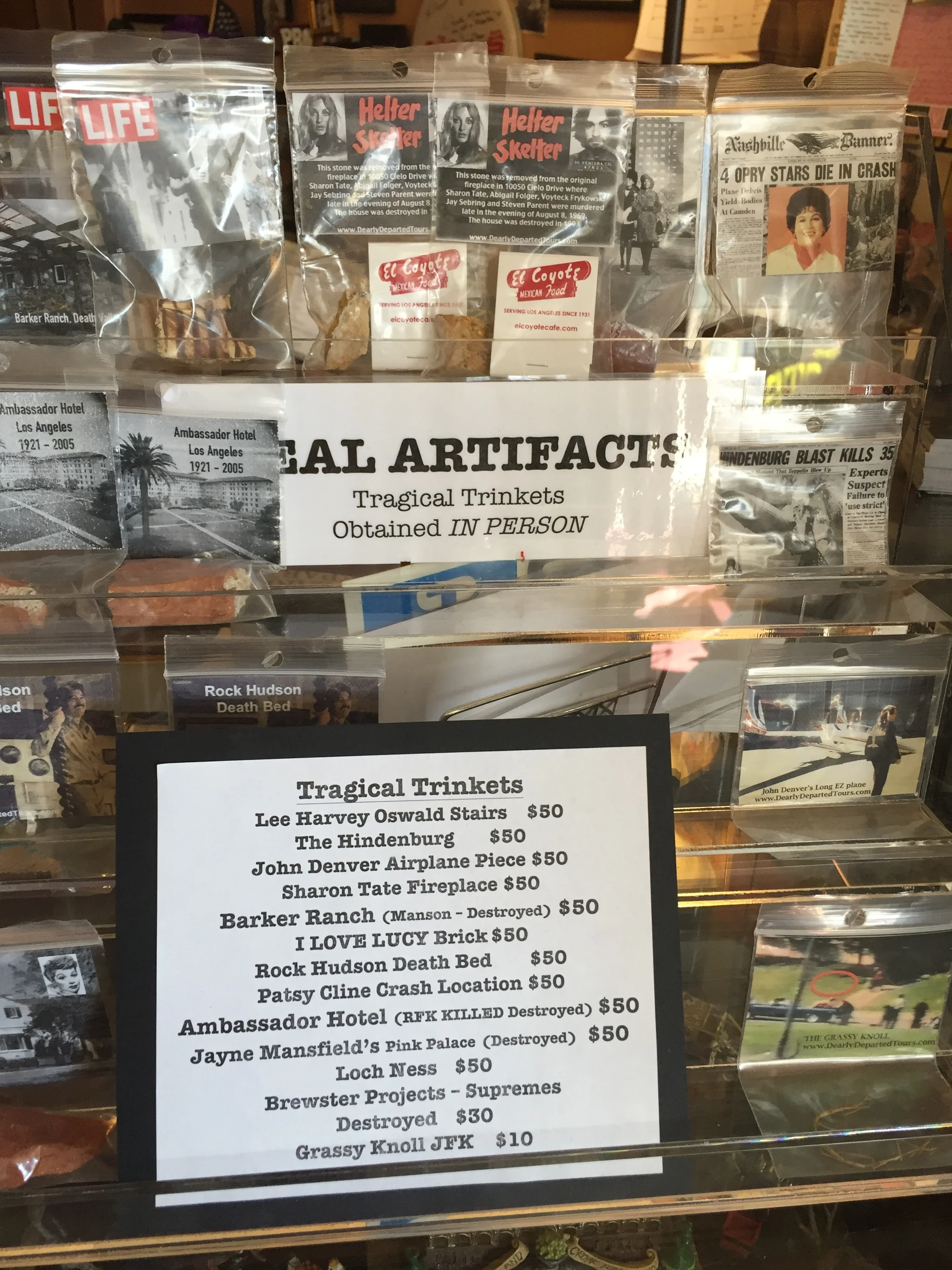

Trinkets for sale in tour museum

The business of death entertainment, particularly that of celebrity, is big business. I participate in it; I seek out this kind of distraction with enthusiasm. I don’t believe that death should be hidden—all hush-hush and never acknowledged—but I do constantly question the allure I find in it. It is a part of life that does foster a lot of pain for those left behind let alone the agony of those experiencing a horrific death. This is perhaps what I struggle with—being entertained by what ultimately involves another human being’s pain.

This realization is a long way from my frolicking among graves and occasionally swiping pennies from the departed. It was wrong for me to steal tokens left with care for dead assumedly by loved ones. Even as I child, I knew I was wicked in taking the pennies. I wasn’t taking them because it was money; I wasn’t assuming I could collect enough to buy some sort of trinket or piece of candy—the penny was the trinket. It was better than any penny found on the sidewalk. It was a dead man’s penny and it held the magic of the taboo and unknowable "other side." That is what I understood in museum owner’s filching of Hollywood’s tragic artifacts. That made sense.

Eva Gabor & Shelley Winters' funeral flowers

When the tour van finally rolled up in front of the shop, I felt anxious and consumed with my conflicting thoughts and emotions. Also, I experienced immense titillation to see where this adventure would take us. Our guide who would be driving the van appeared to be the owner’s right-hand-man. He was enthusiastic and comical, a lover of history which ultimately brought him to this gig at Dearly Departed. He revealed to us that to him death and history were symbiotic; his fascination with death was just as much a celebration of past life, narrative, and myth. Our various stops (not stops so much as rolling dive-bys) included not just places where tragedy occurred but also places simply connected to those long gone. We drove by the restaurant where Sharon Tate had her last supper, Bungalow #3 at the Chateau Marmont where John Belushi of a drug overdose, the Playboy Mansion, Barney’s Beanery where Janis Joplin last partied the night she died, the Alta Cienga Hotel where Jim Morrison once lived, and the Viper Room where River Phoenix collapsed and died of cardiac arrest brought on by an overdose of morphine and cocaine.

It was this moment, paused in front of the Viper Room that I experienced the most distress when our guide played for us the 911 call from the Phoenix’s younger brother, a frightened 19-year-old Joaquin Phoenix, attempting to save his life. The audio of this call is nothing that can’t be found on the Internet. I’m positive I’ve heard it before on some celebrity gossip program. Parked momentarily in front of the club, however, staring at the very payphone over which a young man pleaded with the operator to send help for his big brother, I almost couldn’t take it. His voice sounds small but urgent, cracking between the sobs of panic and despair. It was not entertaining. It was sorrow. I didn’t want this penny. I wanted to throw it back into the well of death and keep driving. What is this strange charm that so many of us find in moments like these? Why, even though we recognize the despair, willingly engage with or visit or buy tragedy? I don’t have answers for these questions but, like many others, I won’t stop the quest. Maybe, someday, like the contents of my pail, the meaning will eventually reveal itself.

Trista Edwards is a poet, traveller, crafter, creator, mermaid, and an old soul. She currently serves as Co-Director of Kraken, an independent poetry reading series in Denton, Texas. Her poems and reviews are published or forthcoming in The Journal, Mid-American Review, 32 Poems, American Literary Review, Stirring: A Literary Collection, Birmingham Poetry Review, The Rumpus, Sout’wester, Moon City Review, and more. She recently edited an anthology, Till the Tide: An Anthology of Mermaid Poetry (2015).