BY TRISTA EDWARDS

When you Google death positive movement one of the first entries you will see is a link to the Order of the Good Death. If you click on the Order’s mission statement, you will find eight delineated points on what it means to be death positive. In short, each point implores the reader to recognize that hiding the dying and death (both physically and conceptually) will do more harm to our society than good.

At the bottom of the page is a petition to join the Order of the Good Death and form active allyship with the death positive moment. In adding your name, you become part of a society of individuals who actively strive to challenge and change the way (particularly Western) culture deals with the topic of death, grief, the body, customs and rituals surrounding our earthly demise, and the capitalistic industrialization that has swallowed up all aspects of our dreaded "end."

The founder of the Order, Caitlin Doughty, is a truly Renaissance woman. She is a mortician and owner/operator of her west coast nonprofit funeral home, Undertaking LA, which allows families to reclaim rightful control of the dying process and the care of the dead body with home funerals, bathing and shrouding the dead, and natural burials. She is the host and creator of the YouTube series Ask a Mortician (If you have not heard of this series you must go watch it like now!), which features short, comical segments that answers all manners of our curiosities about morality. Doughty educates and delights with such topics as The Foreskin Wedding Ring of St. Catherine, Coffin Birth, and Open Eye Wakes & Body Farms often from her own (swoon-worthy Victorian styled) living room.

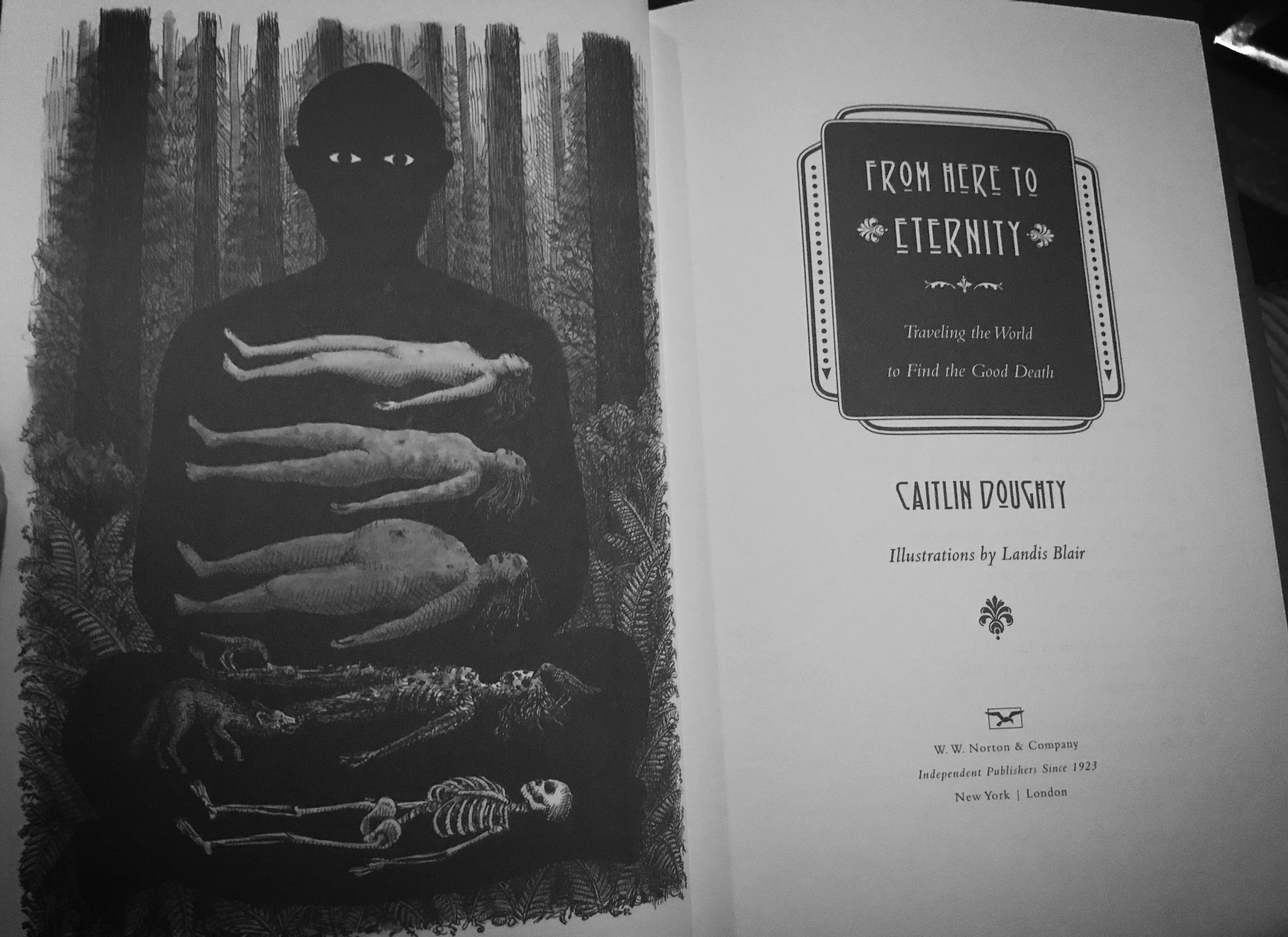

And, AND, she is an acclaimed author of two books—her bestselling 2014 memoir Smoke Gets in Your Eyes & Other Lessons from the Crematory (This book is a stunner and changed my life! I bought copies for friends and sent it to my parents knowing that we had to start a conversation about our impending demise and our desired familial roles when ol’ death came a-knockin’. Good family times abound!) and, most recently, From Here To Eternity: Traveling the World to Find the Good Death.

RELATED: On a Family History of Cancer, Death, & Dreams

Basically Caitlin Doughty is an all around death babe (I recently described her to a friend as the Bettie Page of morticians) and I was major crushing on her when I phoned her up at her home in California to talk about her latest book.

In From Here to Eternity: Traveling the World to Find the Good Death, Doughty takes us with her across the globe to discover how other cultures care for the dead. She investigates various rituals, body composting, sky burial, kotsuage (the Japanese custom in which relatives use chopsticks to gather the bones from the cremated remains of their loved ones), the Bolivian practice of keeping ñatitas (wish-granting, oracle-like human skulls), and much, much more. Doughty explores how other cultures maintain relationships with not only death but dead bodies-relationships that go beyond the preliminary funeral and continues years after a loved ones’ initial passing. This prolonged care, for many cultures, is an essential part of mourning that aids in (and more importantly doesn’t hide) the grieving process and promotes healing through this direct confrontation and personal care for the dead.

Doughty peppers this book, just like her last, with her witty and unique sense of humor that fills every page with absolute candor and macabre enchantment. Additionally, Doughty collaborated with pen-and-ink illustrator Landis Blair who infuses the narratives with striking artwork that brings visuals to the various cultural practices she encounters.

Here, Doughty and I chat (edited for length and clarity) about about her new book, the feminist aspects of decomposition, witchcraft, and mourning:

TE: For many cultures outside of the U.S., mourning is not just a feeling but also an action. It is often a performative and welcome ritual. This was most apparent to me in your chapter with the Indonesian families who provide on-going ritual care for their mummified dead. So it seems it is not just the dead body we are afraid of in the U.S. but out, performative grief. Could you share some of your thoughts on why you think Americans are expected and maybe even desire to conceal our grief as it relates to the dead?

CD: There’s no question that our western culture, at least in the Victorian era, had a more interesting and complex relationship with mourning. And it was more performative specifically for women. There were mourning rituals, there were certain clothes that you wore, pins you wore, wreaths on the door, locks of hair, jewelry and all these very specific and outward cultural mourning practices that we had. At a certain point there was a backlash against that and that performance was considered too ostentatious for the general public and it was brought under. Obviously there are still cultures within Americans that outwardly grieve the dead. The first one that comes to mind is the African-American community where grieving, especially tragic deaths, is very public. You have the memorial t-shirts, bumper stickers, tattoos. The other day I saw a memorial sheet cake. This is kind of similar to what we had in the Victorian era where people had these signposts that said "Hey guess what, I am in mourning and I am grieving." I think this one of the things that people struggle with now, especially if they have had a very tragic death occur, like that of a child or partner, is the very limited and socially "acceptable" amount of time they get to grieve. We no longer get to have the visible representation of our emotional pain that provides a signpost that says "Hey, I am in the liminal space between two worlds. I am a griever and I need more time. I need more time to be able to talk about it, I need more time to be able to speak its name and to exist in a space where I am not okay." I think we would be a more high functioning death culture than we currently are if we could more openly participate in these rituals.

RELATED: Hair Jewelry, Post Mortem Photographs and iPhones - A Lineage Of Haunting & Desire

TE: A concept you share that really resonated with me in your book was in the chapter set in North Carolina at the Forensic Osteology Research Station (FOREST) facility (where an organization, the Urban Death Project, is at the forefront of composting human donor bodies). This concept was the idea of decomposition as a radical act, particularly for those socialized females. To quote you, you say—"Women’s bodies are so often under the purview of men, whether it’s our reproductive organs, our sexuality, our weight, our manner of dress. There is a freedom found in decomposition, a body rendered messy, chaotic, and wild. I relish the image when visualizing what will become of my future corpse." That is so powerful. That to choose to not be chemically preserved and to choose a natural death and allowing your body to partake in natural decay is, as you write, "a way to say I love and accept myself." My question is, what other death rituals have you encountered that read as particularly this combo of female and rebellious?

CD: Well, I also write in my book about Bolivian ñatitas (human skulls that act as oracle-like objects and are kept in the homes of village women). What I ended up really getting from that was it is so easy for so many in Western society to look at folk traditions and folk magic around deaths in other countries and say "Oh, isn’t that cute? Isn’t that quaint?" There’s an allowance of it but also a fear and an infantalization by many that don’t understand it. What I learned was this is a place where women really do control the ritual. They have these oracle-like skulls in their homes and they interpret the dreams they receive from the skulls to people in the community. They help people in their village with problems that range from finances to health to love. The women who keep these skulls really have this power connected to death that the Catholic Church (the dominate religion in Bolivia) and men don’t possess. It is the very powerful thing because it is not just this cute old lady with her quirky skulls…it is an influential woman, a witch healer essentially, who is in this tremendous amount of authority within this community that believes in the power of the skulls. That was really powerful for me because I think in a more secular way that is what FOREST is trying to do with composting the dead. Men have taken death care away from women. 150 years ago we were allowed to be put into the ground in a simple wooden coffin and decay. Embalming was made by men, initially for men, and then kept going because of the financial interest involved in that industry. So, particularly women, who don’t want to participate in that cycle anymore not only makes that choice a radical act as in it connects you back to nature and to our own natural cycles of our body and decay but it is also radical in every time we choose to decay in that way we are taking money from this industry created by men who take positions in death culture away from women.

RELATED: A Water Ritual For Grief & Trauma

TE: Your response really leads into my next question. I know you also have a degree in medieval history and you wrote your thesis on medieval witchcraft theory. The witch is a very important and powerful symbol for us at Luna Luna, both personally and aesthetically. Some of our editors and many of our readers are practicing witches who do magic in their daily lives. So when I read the chapter on the Bolivian women and the ñatitas, the women very much seemed like the emblematic village witch and you just elaborated on how powerful that is, however, I was wondering if you have a favorite witch, either real or fictional?

CD: Oooooo. What a great question! There is this book called Shaman of Oberstdorf and the Phantoms of the Night. It is amazing and I read this for my thesis in college. Chonard Stoecklin was a mystic and an occultist who lived in sixteenth-century Germay. The book focuses on his arrest, trial, and execution for witchcraft after he experienced a series of visions. His life and death also led to a series of other executions in the town for women who were also accused of witchcraft. It is a fascinating book and I really recommend checking it out and reading up on Stoecklin.

TE: So you have two books under your belt in addition to your amazing Ask a Mortician series but like all creative types you probably already have other creative project stewing in your mind. Is there another space you want to explore in the future on the death positive movement through writing or in another medium?

CD: Oh wow, I have too many things floating around to count. I have all sorts of bring dreams that myself and others are working our way towards. We would love to expand the funeral home I have here in Los Angles. We would love a bigger physical space that could hold local events and educational workshops for the community to be involved in death care in a more meaningful way. They are still working on a television show of my first book. We’ll see if that ever pans out. We’re wanting to write more books and make longer documentary- style videos about the death positive movement. There’s so much I want to do to keep this effort growing.

TE: My last question is purely me asking for selfish reasons. I saw on your Instagram that you recently did a talk at the Death Salon on post-mortem pet possibilities. I have two dogs and I would love to learn more on this topic. I was wondering if there was a recorded version of this talk or other resources you could point me towards in pet death care?

CD: Oh, yeah. I don’t think there is a recorded version of this talk but it is based off a blog post I did about my cat. The Meow, called "The Life and Death of a Most Belov’d Meow." It is the initial post I wrote when my cat died and I talk about the things I did for her when she died. First, is I had home euthanasia. I had a vet come to the house to put her down. She never really knew what was going on and quietly fell asleep in my arms. There was no stress for her and it was really meaningful for me because I could fall apart right there in my own living room, not in some vet’s office. The second thing is I had a wake for her in my house and laid her out for day or two on a bed of rose petals. Friends came over and brought snacks and hung out. And the third thing is I had a natural burial on my friend’s land. We got to dig the hole and put her body in and put the dirt and flowers on top of her and perform the whole ritual. This is really all the stuff I advocate for humans. Of course, I was really sad that my beloved cat was dying but, as I say so often for human or even animal deaths, when you really get in there and perform the ritual and you are present then by the end you really feel much better about it. You are not done grieving but you got to be there with them the whole time. You get to dig deep into your grief and that is what starts the journey to healing.

Trista Edwards is a contributing editor at Luna Luna Magazine. She is also the curator and editor of the anthology, Till The Tide: An Anthology of Mermaid Poetry (Sundress Publications, 2015). She is currently working on her first full-length poetry collection but until then you can read her poems at The Journal, Quail Bell Magazine, 32 Poems, The Adroit Journal, The Boiler, Queen Mob's Tea House, and more. She creates magickal candles at her company, Marvel + Moon.