BY SOOEY VALENCIA

The eye doctor said that the blindness would come in the night and I would wake up one day seeing only darkness. He forced out a smile as he delivered the news, settling himself in the swivel chair in front of his computer to record the further deterioration of my eyes--the tap-tap-tapping of his fingers sounded like the crackling of a fire. This man was the second doctor to tell me that I was slowly going blind, that the glaucoma that came with my mild cerebral palsy was spreading like a school of termites eating away at my sight.

The February sunlight peeked through pale-green blinds. Outside, the bending trees made dancing shadows, their leaves waving like a cluster of lady fingers. The entire room filled with the weight of cold, dead air. My insides clenched as I sat back, uneasily fitting myself deeper into the cushioned chair, making outlines of my body into its leather, my palms tracing droplets of nervous sweat on the armrests.

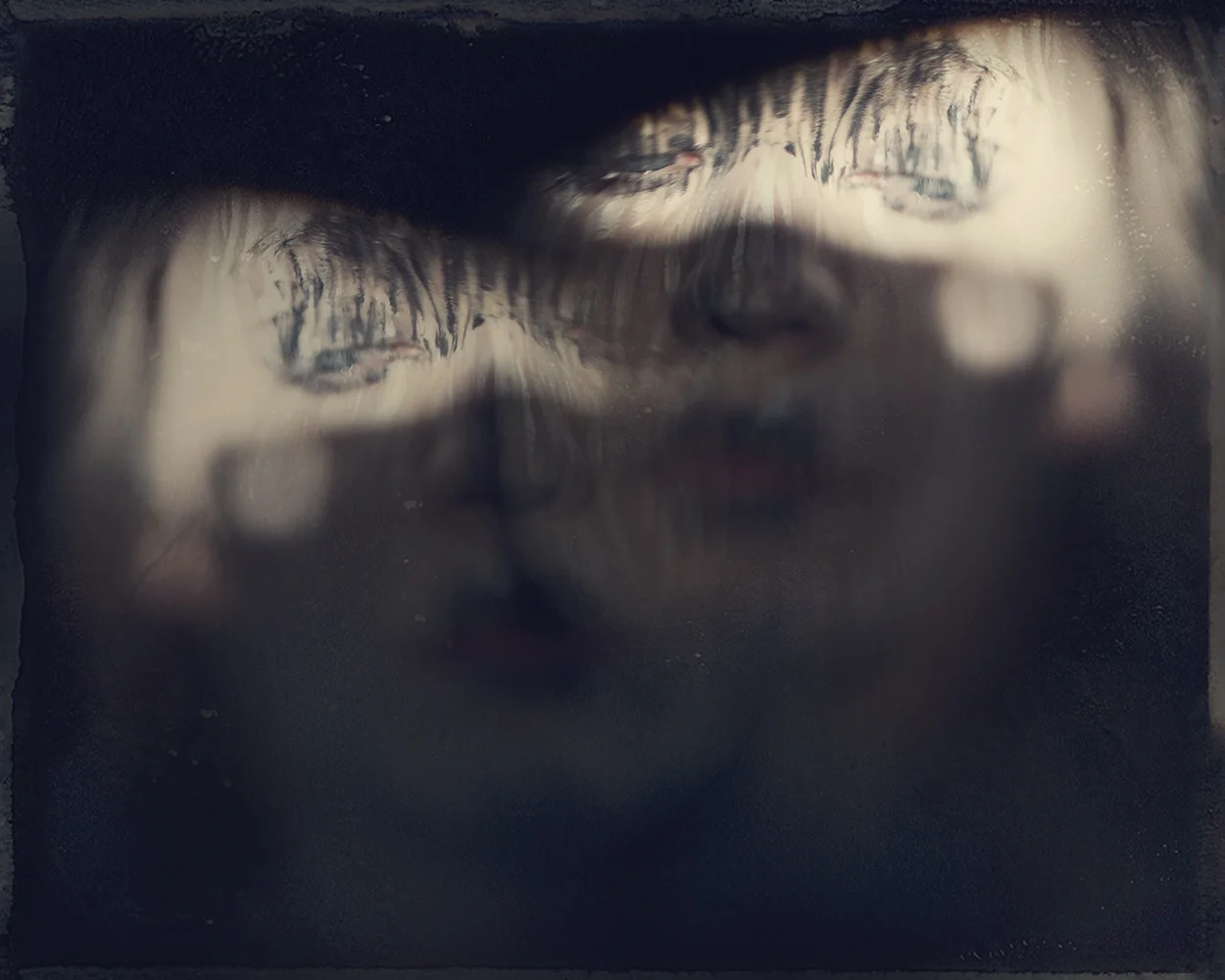

My eyes wandered around the room, looking for a distraction: a clock hung on the wall next to the door, its lazy hands read two-thirty. The calendar under it told me it was Wednesday. Life-like illustrations of eyes watched me, their veins spreading like leafless branches, some of them looking like the insides of a fish. In front of me, the slow quieting of letters on the Snellen Chart.

I closed my eyes, hearing only the rapid clicking of the doctor’s mouse. Earlier he had shown me a chart. "The insides of an eye look like a doughnut," he explained, pointing at the series of pictures. "The bigger the hole in the doughnut, the smaller your visual field gets." The pictures that followed showed what looked like the phases of the moon, or what happens when somebody shades an oblong, hands moving in circular motion from the outside in.

I tried to imagine how it would be like to see the world once the disease had won: first in fragments, then in shadows until my eyes gave out like a pair of faulty light bulbs, and I would see only blackness. No light. All that I have known about the world would change. All color, drained. The ground would feel like quicksand and I would grope around like a newborn.

Ever since I was three, a trip to the eye doctor’s office was never a thing to look forward to. The morning started with the ringing of an alarm clock and the sound of knocking, Auntie Zendy’s voice outside my bedroom door telling me to wake up. I got out of bed and rubbed sleep from my eyes after a night of worry.

"I have to go there again," I thought. "That scary, dark place where monsters hide under the brown couches in the waiting room." The anxiety only grew over breakfast as I watched the letters in my bowl of milk, uneaten, soggy and floating.

I remained silent all the way to the hospital, fidgeting in my seat until the car came to a full stop at the Eye Center, and I alighted hesitantly.

"I don’t want to go!" I exclaimed when Auntie Zendy opened the car door, carrying my tantrum-throwing self out of the car.

"You have to go there today, Bee!" she reasoned as we walked. "Do you want to go blind?"

My tears fell at the word. Blind.

The waiting room had only one small orange light that hung from the ceiling. Under it, we saw one another: an old man, the patch of cotton--a cloud over his left eye, a mole spread out like a flattened raisin across his cheek, ending at the tip of his lips; a mother patted her panicking child with one hand while trying to keep his baby sister asleep in the other; a group of old women competed against one another as they counted how many illnesses life had inflicted upon them; the nun next to me clutched a rosary, showing me an icon of Saint Michael and telling me that he was my guardian angel, a fact that did not comfort me at all.

I wondered what kind of glasses I would get to wear next. The oblong ones with pink frames, perhaps? The green catlike ones with yellow lenses that went darker when exposed to the sun? Or the round ones that looked like John Lennon’s? No comfort there.

"Why am I here, Jesus?" I asked the crucifix on the wall. "What have I done? Have I been a bad girl? I am not a bad girl. I drink my milk every day when I am told to. I don’t like milk but I drink it anyway to make my aunt happy. My aunt teaches me to pray every night and I do just what she says. Am I really going blind? Are the hungry monsters underneath the doctor’s couch really going to eat my eyes out?”

No answer.

"Have I really been a bad girl? What have I done, Jesus? Please don’t let the strange doctor hurt me today. Oh please, oh please, oh pl--"

And then, my name floated out of the nurse’s mouth and into the air. I gave my aunt a light nudge, waving goodbye as I got up with trembling knees, the nurse rushing to help me. No family was allowed beyond the waiting area.

The hallway seemed endless. Its walls were lined with black-and-white pictures of houses from the countryside. My hands felt as though a river of saltwater had begun to flow into them, my knees barely held; my toes began to curl rigidly inside my shoes, the beginnings of sweat on my brow. Who was this old man I was about to face in the dark room? Why was it so dark? What were all these strange--?

My mouth dried and there was only the smell of stale air. The doctor faced me. He was a tall man with hair that grew out of his head like black threads. He had a long face that curved slightly at his chin, and then up again on the other side. He had a mole on his nose and nostrils that puffed heavily, a few hairs sticking out of them like strands of thin seaweed. His eyes sat under eyebrows that looked like mini feather dusters. He wore a cross expression as he studied the small short-limbed girl in front of him. He greeted me, his voice sounding like a frog’s croak. When he introduced himself, I realized that he had the same name as my late grandfather. I thought, then, that perhaps he was my late grandfather coming back to heal me.

"Grandpa? Is that you?" I whispered.

After a war had broken out inside the doctor’s office--the shrill shrieks of a scared little girl kicking and screaming for her mother, a distraught doctor chasing her with a small bottle of eye drops, comforting words from a brown teddy bear that sat in a chair next to the doctor’s desk, and three lollipops--we found out I was cross-eyed.

To the dismay of my three-year-old heart, I did not get to choose the glasses I would get to wear next. The doctor did not even ask which pair I wanted. Instead of the glasses I imagined earlier, I was given a special pair with thick, anti-glare, multi-coated lenses and frames--big words that I did not understand--that weighed heavily on top of my nose.

These glasses became my childhood’s worst enemy. I took them off every chance I got and the adults reprimanded me to put them back on saying that it was for my own good.

I believed that my glasses had feet of their own. When I woke up in the morning and found that they were no longer beside me, I smiled because that meant that I would not have to wear them until I found them again. I walked around bumping into things until my yaya handed them to me, saying she found them under my bed while she was sweeping. I left them on the headboard once she returned to her chores, and there they would gather dust.

It was only at the age of six--when my eyes could no longer do with scratched lenses and chewed-off nose pads--that I gained a deeper appreciation for my glasses. At school, the children christened me "Four Eyes." In my defense, I would say that I was lucky to be wearing glasses because that meant that I could see double and my eyesight was stronger than theirs, something that I had begun to believe myself. I was the Great Four Eyes and I had superpowers! Some of them were amazed and believed me, while the others--being the unimaginative children that they were--started to avoid me, thinking I was strange for believing such thoughts.

"Four eyes! Four eyes! Loony! Crazy! Ha-ha-ha!" Their laughter rang out in unison at the school’s playground. "She thinks she has superpowers but she’s just a nut! Ha-ha-ha!"

The leader of the bullies snatched my glasses from the top of my nose, threw them onto the ground and crushed them with her left foot. A crunch and my glasses were gone. The group left me alone and, as tears began to well up in my eyes, I bent down to pick up the shattered pieces.

I watched them leave and realized that they were right not to believe me. I was strange for entertaining such thoughts. My eyes were not getting better at all. It was not good that I was seeing double. I did not have superpowers and their eyesight was stronger than mine.

Another dreaded trip to the eye doctor at the age of eleven found that I had astigmatism. I could no longer go a day without my eyeglasses. Without them, everything became mere paint smudges, a spillage of colors and then, tired eyes.

Again, I questioned why such things were happening to me. Why wasn’t anything getting better? I wore my glasses every day. I did all my homework and read all that I was asked to at school. I didn’t even play computer games anymore. I was a good kid. My eyes were being put to good use, so why were they dying?

The blindness started to develop at the age of thirteen. Life has become a flowing cycle of eye drops that have to be applied three times a day, fear at the slightest headache that turns into a migraine (a knife splitting a coconut!), and countless visits to the doctor.

The clock ticks, memory slips.

Each tick, memory’s root.

A reminder to never forget each hue, each smell, each texture, each movement, each sound. I will have to remember these. They must live in my mind’s eye, playing over and over until the memories appear like scenes from an overwound video tape.

To remember, color.

Blue sky mornings with clouds strewn over it in the day like a a woolen blanket, turning gray at the scent of rain. The green grass afternoon playing in my grandmother’s backyard. The rust-like brown on tree branches during the hottest months of the year. The orange sunset scattering like an egg yolk. The violet butterflies that would appear inside my aunt’s house, visitors coming to see me.

I often wonder if these colors would stay the way they are, the way I know them to be. Would I forget them even if I tried my hardest to remember? How exactly does a blind person see? Do dreams come in color? In a series of black and white pictures? Or does the world just become pitch black?

To remember, feeling.

To remember rain is to remember how to feel. I am the Rain Girl. Walking the streets of Manila, the rain in my constant companion. I walk without an umbrella, feeling it like small pinpricks, raindrops coming down from the sky. I become one with the rain. I join it as it dances, making its own music as it hits the asphalt. I am thirsty for its freedom. I return home drenched. It is inside me: in my shoes, in my hair, soaking my clothes, fogging up the lenses of my glasses giving them a free bath.

I wonder if I would still love the rain when the blindness takes over, if I would still speak of it as I do now--with a hunger for it to come. How would it greet me when it does come, this old friend? Would it still kiss my skin tenderly as it has? Or will it turn into an enemy? Will each rainy day turn into a war: me against the water?

Perhaps it would trip me in my tracks, making me fall and grope, my entire body feeling the hard earth. Perhaps rain would no longer be light on someone like me. The raindrops would shoot from all angles. Hitting, hitting, hitting--the merciless army! I would never come out of the house again at the sound of the horrid pitter-patter--the music of rain on the roof, the rain dance.

To remember, smell.

Christmas. The cold breeze that enters through the door of my grandmother’s verandah, accompanied by the sound of tolling church bells. Her room smelling of flowers as she sits at her boudoir getting ready for midnight mass. The wafting smell of cocoa once morning had broken.

To remember, sound.

The city’s cacophony--the whir of vehicles speeding by emitting thick, black puffs of smog. They leave me in a momentary state of disorientation, my heart’s sudden leap out of my chest, the only proof of their passing. The rattle of a street child’s cup of coins, the deafening sound of metal jangling.

To remember, faces.

My mother’s round face under a mop of hair. Almond eyes. The curve of her nose. The drooping tips of her shell-like ears. Her lips from which only kind words escape.

The roughness of my brother Carlo’s beard, in case the blindness take the rest of him away from me. My fingers would then feel around for a rough patch on his chin and I would smile at the knowledge of my brother’s presence. I must also remember my brother Billy’s face--his soft eyes, light playing in them.

I must remember my puppy, Prince Vladimir’s kind eyes, the ones that will guide me through a life of darkness. I wonder, will he know that I had gone blind? Will he notice?

The world is a patchwork of faces and I must remember each one that passes through my life--the faces that arrive and leave. The ones that stay.

And what of the heart? Will it have its own pair of eyes once I go blind? Will it beat once it sees, feels, and knows love? Will any man love me, the blind woman he chances upon one day? Or will he just leave knowing that I do not see him walking away--the sound of his footsteps growing fainter and fainter?

Returning.

The hands of the wall clock have started to move again. It occurs to me that everything depends on movement. The world moves fast and the hands of time will always turn and return, seemingly synched to the clicking sounds of a metronome.

The eye doctor said that the blindness would come in the night.

Sooey Valencia is a writer from the Philippines. She received her Bachelor of Arts degree in Literature and her Master's Degree in Creative Writing (magna cum laude) from the University of Santo Tomas, She won Ustetika Literary Awards for her creative non-fiction and poetry in 2010 and 2011. She was a fellow of the 51st Silliman University National Writers Workshop in Dumaguete and the UST Creative Writing Workshop among others. Her works have appeared in the Dapitan Literary Folio, Tomas Journal, The Philippines Free Press, and Quarterly Literary Review Singapore. She occasionally writes book reviews for the Philippine Daily Inquirer.