BY SANDRA MARCHETTI

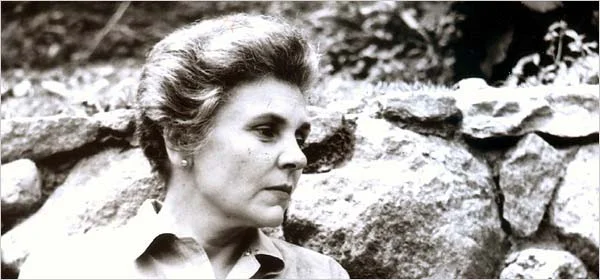

Elizabeth Bishop was a poet whose personal life was fraught with family struggles, questions of sexuality, and a great deal of loss. A casual reader might recall some of these emotions exhibited in her masterful villanelle, "One Art." Filmmakers have even attempted to capture snippets of Bishop’s interior life during her time in Brazil in the recent movie Reaching for the Moon. However, despite the fact that she moved throughout her life and perhaps never found her "place," her readers can sense that she felt a strong tie to family, legacy, and her historical moment. Bishop’s "Poem," a short piece about a puzzling family heirloom, serves as an excellent example of how she negotiated her historical ties, ties that in many ways have formed the basis of my complicated relationship with Bishop’s work.

Akin to "Poem" is Bishop’s more expansive piece, "At the Fishhouses," which begins with the depiction of an evening on the Nova Scotia coast, where the author lived as a child. She describes an elderly fisherman cleaning and packing up for the night. The speaker rehashes old stories with the fisherman, but eventually he melts into the background of the poem. In the climatic final stanza, Bishop steps out onto the wild, frigid coastline and gives voice to what she sees:

Cold dark deep and absolutely clear,

the clear gray icy water . . . Back, behind us,

the dignified tall firs begin.

Bluish, associating with their shadows,

a million Christmas trees stand

waiting for Christmas. The water seems suspended

above the rounded gray and blue-gray stones.

I have seen it over and over, the same sea, the same,

slightly, indifferently swinging above the stones,

icily free above the stones,

above the stones and then the world.

If you should dip your hand in,

your wrist would ache immediately,

your bones would begin to ache and your hand would burn

as if the water were a transmutation of fire

that feeds on stones and burns with a dark gray flame.

If you tasted it, it would first taste bitter,

then briny, then surely burn your tongue.

It is like what we imagine knowledge to be:

dark, salt, clear, moving, utterly free,

drawn from the cold hard mouth

of the world, derived from the rocky breasts

forever, flowing and drawn, and since

our knowledge is historical, flowing, and flown.

"Cold dark deep and absolutely clear." This is "what we imagine knowledge to be." The poem suddenly shifts from storytelling to high lyric, yet Bishop is still so direct, so confident in her wording. We hear her describing the coldness we feel when putting a hand under the freezing tap—that "transmutation of fire." We are at the water’s edge with her, "flowing…since / our knowledge is historical, flowing, and flown." All five senses are charged: the salt is in our nose and mouth, the cold water bites our hands, we see and hear the icy waves with perfect clarity. The music of the language is motion—we, as readers, are in it.

The wording is crisp and candid: "Bluish, associating with their shadows, / a million Christmas trees stand / waiting for Christmas." We imagine the blue spruces all lined up in a row and sense Bishop knows that because of the inevitable march of time, they will eventually disappear. There is even surrealism in the poem; it is the surrealism of everyday life. Bishop says,

I have seen it over and over,

the same sea, the same,

slightly, indifferently swinging above the stones,

icily free above the stones,

above the stones and then the world.

This part of the stanza is particularly rich because each of us has seen "it over and over," the "it" being a favorite lake or park, our living room, or even the yard. Yet all of us have felt a place morph into something different when we stop simply looking at it and instead really engage with the scene. This is when we truly "see" it, as Annie Dillard would say in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. Bishop’s poem reinforces the idea that a concentrated observer of a place can make it new. This is part of what I so deeply admire about Bishop, though the maxim is true of poetry in general: poems have the ability to make the familiar eerie. Even the otherwise ordinary sea becomes a ghoul, or maybe even a new kind of sky, "swinging above the stones, / icily free above the stones, / above the stones and then the world," in this context.

I began to connect with Bishop’s poem on such an intuitive level that I felt I needed to honor it in a poem of my own. My piece, "Cold dark deep and absolutely clear," ends at the water’s edge, as well:

…Not entirely shade

but clear gray out across the ledge

and many measures more, a little water flits

between a split-trunk tree. It is

what we imagine June to be: a sliver

of wet movement, an arc that asks for colors

to ice it hotly and shake the shake of gray.

In this poem I chose not to tackle something so magnificent as "what we imagine knowledge to be." Instead I explored a much narrower abstraction: "what we imagine June to be." However, I chose "At the Fishhouses" as a guide for this piece, and I think of Bishop as a guide still—to bring about that "transmutation of fire."

Elizabeth Bishop is often remarked to be a "Poet’s Poet," partially because she does take on these highly abstracted and sometimes inaccessible concepts. In fact, on visiting Bishop’s homes in Brazil lyric essayist Christine Marshall says,

…I walked around the properties

and observed them from the outside

because I couldn’t get in. This is something like the way

I used to feel about Bishop’s poems.

I still sense this tension when confronting Bishop’s tightly wound poems, and perhaps it is why I have chosen her work as a talisman. In fact, the six perplexing lines that describe knowledge as "flown" at the end of "At the Fishhouses" will serve as the epigraph for my debut collection of poems to be published this year. In some ways, I made this choice simply because the lines still elude me; after reading the poem a hundred times, I can’t fully glean Bishop’s meaning.

Epigraphs themselves can collude with, or detract from, the mystery of the book that is to unfold. An epigraph can be easily ignored by the reader, of course, but a good one resonates like a golden tone. Here, I think of Carl Phillips’ epigraph in Speak Low, chosen from Robinson Crusoe: "…and I could feel myself carried with a mighty force and swiftness toward the shore, a very great way…" In the context of Phillips’ syntactical rhythms, Crusoe is made new. In exchanges like this we are let in to see the world of a book from its creator’s perspective. I search for the symmetry created when voices align, that golden tone, and I most often start drafting a poem when I can visualize the sound of it. Bishop’s description of the invisible, knowledge, morphs to water that we can see and hear: "flowing" and "utterly free." I chose Bishop’s description of knowledge to open Confluence hoping that in letting her lead me, perhaps she would turn toward me again and give me her eyes.

Sandra Marchetti is the author of Confluence, a full-length collection of poems, selected by Erin Elizabeth Smith published by Sundress Publications.