BY ANNIE VIRGINIA

“I don’t ever want to reenact violence or perpetuate violence even when the poems speak, explicitly, of violence. I do not mean to appropriate violence. There are days when it seems the poems fail–or I do–at this. & other days when I feel better about the poems. I have a sense of responsibility in the questions I ask & the ways that I want to stretch & grow in my seeing & writing.” -- Aracelis Girmay, Union Station Magazine

“Words should perhaps/protect us from what happens” -- Dan Chaisson, “The Elephant”

It wasn’t in my plan to start this article this way, but on thinking about the most important parts of Zachary Schomburg’s essay “Poetry As Violence,” I continue to hold in mind his idea that the trauma of violence is in the small details around the violence, and I remember the snippets of memories that occasionally come to me out of nowhere like moths in the night, and that, like moths, I try to bat away before they can land on me. The one that comes to mind first is a confession. It is a memory I’ve told almost no one and I’m telling you here not so you can experience violence, but so you can be humanized in your observance of someone else’s. March 9 (tomorrow, as I write this) marks the sixth anniversary of the day I, at sixteen, downed a bottle of aspirin and tried to go to sleep. What lingers of the violence isn’t the act of swallowing the chalky pills, or the burning in my stomach I couldn’t explain to you if I tried, it isn’t the activated charcoal I forced into my own body, not out of a desire to live but out of the embarrassment of being seen trying not to live.

It’s the memory of my mother returning to my hospital bed with as many items from the hospital cafeteria she could find that she thought I might be able to swallow, my throat burned out with acid. It’s the lemon pie. It’s how I was instantaneously and forever deeply, inexplicably sad about that pie that my mother brought me despite how it was probably $10 a slice, despite how my mom rarely buys sweets, despite how on a good day I’d be so excited to have it, despite how I felt like I didn’t deserve to have something as sweet as pie. It burned going down. The pie was violent in its smallness and continues to live because it’s so small it can hide in the cracks where I’m not quite put together yet.

The rest of Schomburg’s essay, though, I question. Schomburg defines violence as “when something happens to something else.” But wouldn’t this mean that just about everything is violent? The cat jumps onto the sofa. The child passes a toy to another child. The lover kisses her lover. I don’t want the word violence, made sharply lovely by its echo of God’s favorite color*, violet, to be stretched so far that it covers the entirety of existence. Not just to preserve the word, but because I’ve had violence committed against me, and it was not the same as the cat jumping onto the sofa. One of the major differences between the two is harm, which Schomburg fails to examine. Harm is when a person is violated and hurt, when their boundaries are crossed, and when healing must take place afterwards.

Violence is…everything we don’t want in the world, everything we fear, existing alongside the tiny details that make up our lives and dreams. Violence is not just a metaphor or way to be edgy in your art, it’s a real force in the world from which pain and anger arise. It is this conflation of violence and harm that reveals Schomburg’s lack of nuance.

Though Schomburg tries to acknowledge his privilege and lack of knowledge in his discussion of violence, he gives away the privilege of his perspectives with his reference to Jaws, which implies that poets and others are knowingly putting ourselves directly under the guillotine blade of violence and the violence is inevitable. The person here is at fault and the shark is merely acting on its animal instincts. Violence, in the sense of force, may be inevitable, but harm is not. By conflating the two, Schomburg excuses acts of harm as if the perpetrators have no choice. As a woman, I find fault with this. We, women, do not “offer [our] legs up to the shark in the false name of play-- a seduction of grief.” Maybe it’s his use of the word “seduction” that automatically calls to my mind sexuality, sexual power, and sexual violence. But it doesn’t sit well with me either way. There are sharks in the oceans of our lives, absolutely everywhere, and we know it, but we must live. Amongst them. We are not seduced by grief, we are made to live, and live we do, even swimming in the blood of our sisters, which only calls the sharks closer to our own. Violence is done to us. We are harmed. We live despite this. Is our living an act of violence? “Women live their lives.” Subject and object. The sharks (or maybe the mothers of sharks) could say that our determination to live is violence in the face of their power (or maybe they just call it a feeding frenzy).

However, the harm here continues to affect us more than it has yet affected our perpetrators. Now, I can’t unthread the two, but I am a poet as well as a woman, and certainly there is a seduction to writing a poem, knowing that it is Pandora’s box, and finding what violent beasts are born from it, aware from the start that in writing a poem, we are writing what we do not know we know. The violence released from within the poem almost always affects us, the poets, the most; we find in ourselves and in the world what we didn’t know was there and might not have wanted to. This knowledge is power, and the act of writing the poem could be seen as a violence against our perpetrators. As Audre Lorde tells us, “poetry is not a luxury,” and there are women worldwide who may be killed simply for picking up a pen to write. Are these women dangling their bare legs above the mouths of hungry sharks? If/when their legs are eaten, is the violence their fault?

This question brings me to another: Schomburg’s exclusion of the mention of the perpetrator. Does it matter who commits what violence against whom? Are some acts of violence morally (not religiously or politically; we already know about that) sanctioned? Are there hierarchies of violence? If we are to consider the poem as violence, all poems are perpetrators. Or maybe all poets are the victims of poetry. They do drag from us what we don’t write on our OkCupid profiles, tell our mothers, or even whisper to our lovers when there’s no light left to illuminate us. Still, we said yes to this revelation. Can violence be committed against someone who is saying yes? Schomburg claims that writing a poem is always violent because in writing, we are trying to claim and mutilate reality, we are trying to make it our own. (The wrecking or mutilation of something in order to claim ownership over it is, of course, a uniquely patriarchal concept of what “ownership” means.)

But what kind of reality is this? I don’t buy the idea of a fixed and immutable reality that must be broken and violated in order to be made our own; reality is mutable and influenceable, and as poets our job is to explore it in all its depth-- it would be a violence to ourselves to leave existence be without lifting up the corners that were tucked under for us to unfold. Schomburg writes, “But the violence in the poem is when it sees it can flood the mountain, make it float away into a new sea.” This feels to me more like birth than violence, and the excruciating pain of birth tells us that pain is not equivalent to violence. Birth can be agonizing, but there is no perpetrator, and while Schomburg may believe birth does violence to reality, there is in his framework no question of harm. Not every act of change is violent, and certainly not harmful.

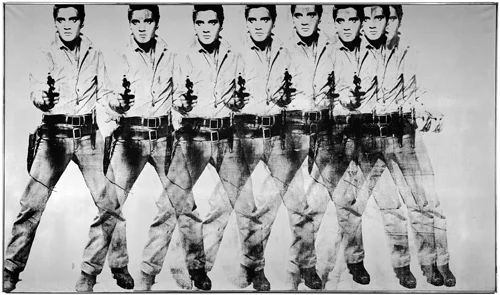

When Schomburg begins writing about how he himself does not understand life-consuming violence and that this is why he is meant to be a poet, and going on to mention Susan Sontag’s belief that photographing a subject is a kind of murder, I believe he moves into his most masculine, most problematic position. Playing with the word “violence” in this way is romanticising violence. Violence is not desired. It is not an art. Violence is not taking a photograph. If taking a photograph leads to harm, it is not because the photograph was taken, it is because of a human response to the photograph, possibly because it, like a poem could, reveals something people did not want to know. Art can depict any kind of violence, but the truest art’s actual violence is against oppression, hatred, societal stricture, expectation. It actively seeks to harm the falsehoods of established ways of seeing; it does not seek to harm people but the systems through which we harm each other.

Schomburg quotes Gregory Orr, who says that the first poem he wrote was fantastical, escapist, and a way of surviving. My own work is obsessed with violence, and often this meeting of violence head-on is my own way of surviving. I have written poems within which violence occurs to myself, my loved ones, friends who have scorned me, and most cathartically, the rapists of myself and other women. These poems act as safe spaces where violence that lives in my blood can come out and play without flowing into my hands and lifting a gun and taking a life. My poems save lives in this way--my own and others’. When I write of things that are not violence, things equally important to making reality my own, such as love, travel, absurdity, the temptation is to use the word “capture” to speak of how I try to catch and hold an experience-- but these poems, like photographs, take nothing of the beauty of which they write. Indeed, the wording itself may be a reason why people may believe art is violent; to “capture” is to “take into one’s possession or control by force.” Poems don’t own anything; they allow the ownership of ourselves. And so they don’t need to be violent to us.

I once sent Buddy Wakefield’s lines, “This is brutally beautiful. So are we. This is endless. So are we,” to the woman I was dating. She became angry, thinking that I, like many men she had met, found her beautiful because of her “brokenness” and my own desire to heal through love a victim of violence. My lover didn’t understand my meaning, which was only that life and we are unbearably lovely and that we go on. Schomburg unwittingly echoes the sentiment of men who find women more alluring the more violated they’ve been in his reference to the children’s book character, Ferdinand the Bull. Ferdinand was allowed to chase butterflies forever rather than fight matadors, and Schomburg believes that in this story, “there is nothing to understand, there is nothing redemptive, there is nothing complicated. If Ferdinand would have met his real fate, we would have loved him, we would have known him, he would have been real and beautiful.” I believe only a person who is naive, who has only faced death rarely and in minimal ways, and who admits having a distant relationship with violence can romanticize violence in such a way.

Schomburg writes, “Violence is so beautiful because it reminds us we’re going to die, and there’s nothing more beautiful than that.” I don’t question the legitimacy of the violence he has experienced, but maybe the violence he has felt has caused less harm than the violence my sisters and I have felt. In the moments of violence when death was a heavy male body on top of our own, we felt no beauty in that. Schomburg misses the point of Ferdinand, that someone who was expected to play an assigned part in the cycle of harm refused to do so. Stories like these are the kind of art I mentioned, they are their own special kind of violence-- violence against the status quo, which is to say, exactly the kind of remaking of reality that he’s busy arguing violence is.

Schomburg goes on to say that he was attacked because of the power his attackers saw in him, and that they when they assaulted him, they fully took that power from him. He believes that his attackers went to bed subconsciously feeling horrible for hurting him. This seems to me to be a viewpoint specific to someone who is used to having power assigned to him-- that is, a heterosexual male. For myself, and many other survivors, to say my power was fully taken from me when I was assault would be to diminish the fact that I lived. Violence, at least that committed against women, isn’t about seeing power, believing in that power, and wanting it for your own; it’s about believing in a weakness upon which you can build your own power by breaking the boundaries of another. And from what I know about violent people, they aren’t going to bed feeling sorry for their lack of empathy. The violent attacker is not a poet, does not wield empathy as a tool of the trade.

Like I said, I agree with Schomburg that the specks of life floating around violence are what make violence matter. If the cousin who died of bone cancer as a child didn’t always choose Superman ice cream that turned her tongue blue or didn’t hold a plastic doll in her pink and grimey hand or have her ears pierced a year before she got really sick, the impact of her death wouldn’t be as deep. If people weren’t composed of lovely, mundane details, it wouldn’t matter if they died or if violence was committed against them. The details are also what illuminate violence, what give barbs to our bad memories.

The word “rape” is used almost as often as it happens: constantly. It does have an impact when I say it, but the details are what hurt most to remember. It kills me when I think that if I had worn shoes that laced tighter and didn’t come off so easily, I might have been snapped out of the dissociation during my rape. The overhead light in my room and the wrongness of it being on. It’s hard to tell these stories, to convey these moments. There is a reason it’s so hard for us to believe in and care deeply about violence done to others. Violence does not feel as violent to us without it storied humans. In that sense, Schomburg’s interest in how to write violence is appropriate, but he may not know what violence is. His ideaslose meaning from being too large and exciting (“everything is violence!”), failing to separate violence causing harm from a more abstract violence of change, breaking, reforging. He then gets too specific, touting the idea that violence is beautiful because we’re all going to die and that’s beautiful!, a privileged, narrow vision overlooking any feeling that we are going to die may not be so beautiful.

Healing, though, too, comes in the details and has nothing to do with violence. When my head gets stuck in the details of my assault, I bring to mind a porch swing on a beach where three ladies sit together in silence. One is usually red-headed, one is black, and one is fat. I pull myself into them by adding details to their appearances, which add nuance to their friendship. I write poems, too, that require no violence. If my poems break boundaries, they are my own, and no harm is done, or my reader is invited to break boundaries with me, and no harm is done. There can be shock, revelation, newness without violence, Schomburg. The line right after the ones I sent my lover in Buddy Wakefield’s poem is “We can heal this”, and that poem speaks truth without harm.

*Read Alice Walker

Annie Virginia is a Southern runaway with a BA in poetry from Sarah Lawrence College. She is known for her vigilante justice and resilience. Annie marks in her memory the cities of Italy and eastern Europe by the falls she took in each and their accompanying scars. Her plan is to earn an MFA in poetry, become a professor, and live in the woods with her partner and two dogs. Her work may be found in The Dead Mule School of Southern Literature, The Literary Bohemian, Broad!magazine, the first ever queer South anthology by Sibling Rivalry Press, and Cactus Heart magazine.