BY ANNE CHAMPION

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared on our old site.

When we discuss the War on Women, we’re generally talking about reproductive rights, victim blaming, slut shaming, and strange Swamp Creatures named Donald Trump who dismiss a woman’s personhood by asserting that she’s on her period.

And yes, women face these and other attacks on their agency, worth, and sense of self on a daily basis. In fact, we generally absorb these political attacks on womanhood without so much as a flinch: we are so used to all pervasive belittlement in politics and pop culture that it’s just a fact of life. That’s not to say it isn’t monumentally frustrating and emotionally draining.

However, there’s a very literal aspect to the War on Women that only women seem to acknowledge and know intimately: we could die for being women. If not death, we have a high probability of being raped or beaten. And yet, men still often see this as a "rare" occurrence; in fact, even some women do. It’s a protective mindset: if you don’t acknowledge its high likelihood, then you can rest easier that it won’t happen to you.

And when we see the myriad news stories of men killing women, men raping women, men beating women, we react in various ways that covertly deny the problem: we doubt the rapes, we demand more evidence, we assert that women have reasons to lie because they can’t cope with being jilted in love, we ask what the woman was doing to deserve being raped or beaten. And if she was killed—we attribute it to the work of a deranged man.

There’s no doubt that a person who murders outside of self defense is not mentally well. However, that derangement is not some psychological mystery—male derangement is a product of patriarchy. And women go through their whole lives with a backdrop of violence and fear littering their landscape.

Let’s start with some statistics:

- More than 10 million women are physically abused by an intimate partner a year.

- 1 in 3 women have been victims of some form of physical violence by a partner.

- 1 in 7 women have been stalked by an intimate partner.

- There’s an average of 20,000 phone calls placed to domestic violence hotlines a day.

- 1 in 5 women will be raped in their lifetime.

- 72% of all murder-suicides involve an intimate partner. 94% of the victims of these murders are female.

- 34% of all women killed are killed by an ex boyfriend, husband, or lover.

- 10% of all women killed are killed by a male stranger.

- 31% of all women killed are killed by a male family member or friend.

(National Coalition Against Domestic Violence)

Last weekend, I received a text message from a woman I’ve never met. A woman who is the girlfriend of a man who sexually assaulted me with his friend while she was pregnant with his child.

I don’t want to give the full story of how this happened: I partially don’t speak of it because it’s traumatic. But I also don’t speak of it because I’m not safe to do so.

I wanted only for this man to disappear from my life, and yet, here was this woman contacting me, seeking answers about his infidelity long after it happened.

And because I’m a woman, and because I feel deep empathy for women in abusive relationships, I spoke to her candidly. And she shared many disconcerting details of his abuse of her as well.

He’s routinely beaten her, raped her, threatened her life, and blamed her for all his actions. If only she stopped trying to "be the man in the relationship," if only she lost weight, if only she was better in bed, if only she appreciated him more, if only she stopped nagging him about his cheating.

In listening to me, this woman started to realize the illogic of these accusations against her. He had no "if onlys" he could say about what he’d done to me. He barely knew me.

It felt healing to talk to her, even though it drudged up traumatic stories, and I wanted to support her any way I could. Then I got a voicemail from him:

"If you don’t stop talking to my girlfriend, I’ll show you my bad side. You have not seen my real bad side, but you will if you don’t stop."

The threat was chilling enough to put me on edge, to make me jump at every car passing my house, to give me violent nightmares.

The next day, I got an email from her. He’d showed up at her job to ask to pick up their daughter together from daycare (yes, he has a daughter). She considers him a good father, so she agreed. When she got in the car with him, he pulled a knife on her. She tried to run out of the car and call 911, but he attacked her and smashed her phone. Finally, some people in the parking lot broke it up and she was able to run inside. When she came out, he was gone.

Now I sit here every day, periodically checking in with her, only to be sure she’s still alive.

This story is not a rare occurrence. This is a type of story that nearly every woman knows in some form. It happened to them. It happened to their mother. It happened to their friend.

Furthermore, every woman carries a strong undercurrent of fear with her everywhere she goes: please don’t let this happen to me. Or worse, please don’t let this happen to me again.

Several years ago, I took out a restraining order against a man I dated for four and a half years. Every time I caught him cheating on me and tried to leave him, he’d climb up my fire escape, break into my window, and start yelling, crying, and smashing things in my house. He had a child, and I always hoped I could rationally talk him out of this behavior rather than call the police, and the truth is it is hard to get law enforcement involved against someone you loved; you feel responsible for potentially ruining his life, even though this is illogical.

But after I developed severe anxiety attacks that even medication wasn’t helping with, I finally had enough and called the police.

When I was a teenager, my friend walked in on his stepdad beating his mom. He tried to break it up and his stepdad stabbed him in the heart with a pocket knife and killed him.

One of my friends confided in me that at 14, a teenage boy assaulted her in a car and tried to rape her. She was able to fight him off, but she saw him years later when he was in college. She asked him if he remembered assaulting her, he cried and said no.

Another friend of mine was in a violent abusive relationship for years, always covered in bruises, but unwilling to tell anyone what was going on in her relationship.

When I go on dates, I always carry mace with me.

When I go on dates, I always tell my friends who I’m with and where I’m at, in case they will have to talk to the police.

When I go on dates, I almost always get texts from friends when it’s been several hours: "Are you ok? Are you alive?"

Our fear is daily. It’s all consuming.

Like most women, I can’t go outside without being cat-called or sexually harassed or simply gawked at in an intimidating way. You try to ignore it, but with every one you wonder if this will be the man that will kill you for ignoring his advances.

Growing up, my mom raised me on Lifetime movies and soap operas: I saw women beaten, women raped, women cutting off men’s genitals, burning a man’s bed while he slept, and women killing a man who was about to kill them. My mother always explained the threat of men very matter of factly: almost every woman will get hit, raped, and possibly killed.

I watched the O.J. Simpson trial on television with my mother, and watched his celebratory smile after his not guilty verdict. "Men that kill women are often very charming," my mother said, "it’s very hard to believe they could do it. It’s just how the world works."

It is indeed. I’m grief stricken, but unsurprised when I see a man has killed two people on a news cast.

The bodies of dead women crowd the periphery of every girl growing up in this world.

It’s not domestic violence; it’s patriarchal violence, and its root cause stems from the damaging ways we socialize men. Men in America are taught to be emotionally illiterate, while also knowing that they have significant power and are more valuable than their female counterparts. Therefore, conflict is often managed through a violent response. And any kind of perception of emotional rejection manifests as anger and aggression, because rejection is a threat to entitlement and power. It is an unhealthy way to raise men in a society, but women face the most brutal consequences of it.

Meanwhile, women, encouraged to express their emotions in a healthy way, are deemed weak and called crazy. It’s baffling in its logical fallacy, but the values persist.

All around us, pop culture continues to degrade women. We saw photos of Rihanna’s beating, but we still dance to Chris Brown. We hear music that calls us "bitches" and "hoes"—these gendered terms of aggression are seeds that feed patriarchal violence.

Recently, I cut ties with a friend of mine, and called him out on his misogynistic music. He’s a poet and a college professor—he’s even taught books by the incomparable Roxane Gay—and yet his music says, "We Be Fucking Hoes." He calls women bitches in casual conversation. He starts off his album with a string of voicemails of women trying to get his attention and him deleting each one. He raps about "Sliding into DMs"—a type of social media harassment that women experience daily that men feel entitled to.

As long as our pop culture makes it acceptable for women to be degraded in this way, we will keep dying from the War on Women. As long as male ego, dismissal of women’s voices, and degrading terms that belittle women’s value pervade our cultural landscape, men will not be able to process that women are humans, and that hitting, raping, and killing are inappropriate responses to women, no matter what the circumstances.

Men calling women "bitches," "hoes," "sluts," and any other derogatory name needs to become just as appalling and unacceptable as a white person saying the "n" word. We don’t accept the "n" word because it carries alongside it a history of oppression, violence, and death. Derogatory names towards women carry the same history—and we need to start confronting that violent history and actively rectifying it.

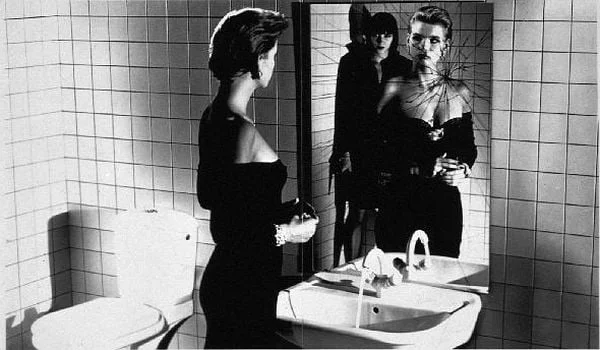

Last summer, my friend and I went to Thelma and Louise at a local theater. The characters are beaten, raped, robbed, and sexually harassed. They kill a potential rapist, and as they run from the law, they kill other men who make lewd gestures and remarks at them. After their rampage, as the cops are closing in on them, they decide to drive off the cliff holding hands.

I’d seen the film before, but my friend hadn’t. She was in tears. We hugged each other. It’s no secret why the film is so iconic, why it hits such a deep nerve to so many women. We all wish we could have the power to combat male violence—we would all drive off that cliff to escape this terror if we had the guts.

Anne Champion is the author of Reluctant Mistress(Gold Wake Press, 2013) and The Dark Length Home (Noctuary Press, 2017). Her poems have appeared in Verse Daily, Prairie Schooner, The Pinch, Pank Magazine, Thrush Poetry Journal, Redivider, New South, and elsewhere. She was a recipient of the Academy of American Poet’s Prize, a recipient of the Barbara Deming Memorial grant, a Pushcart Prize nominee, a St. Botolph Emerging Writer’s Grant nominee, and a Squaw Valley Community of Writers Poetry Workshop participant.