BY JENNIFER CLEMENTS

Editor's Note: this essay was originally published in The Transnational Vol. 4.

#1

The courtroom smells like airports from the 1980s and I am thinking about the substance of carpet and its trappings when they call my number for the voir dire. They pose questions which ignite other questions I’m not allowed to ask.

Are you an expert in psychology or psychiatry. Do you have any strong feelings about, or knowledge of, bipolar disorder. Have you ever been a victim of assault, sexual or otherwise. Do you know [name of defendant] or [name of victim]. Do you live near [neighborhood where crime took place]. Do any of your family members or close friends work for the city police. Can you fairly and justly consider the facts of the case.

I’ve moved often enough that no one has summoned me for jury service. I answer as honestly as I’m meant to and return to my seat. The woman next to me wears a fur coat long enough to brush the floor. She’s pouring hand sanitizer into her palm.

There is a switch on the wall that broadcasts static over the loudspeaker. They use it now, as they question hundreds of prospective jurors. They use it during the trial when the judge asks the counselors to approach the bench. No one ever asks me if I can read lips.

#2

The news that I’ve been empaneled comes as a physiological burst, my cells falsely personalizing the acceptance, and I remind myself this is not the cast announcement for a high school play. Arthur Miller did not pen this courtroom drama and civic responsibility is not a prize. My selection is precise and impersonal and has little to do with the ways in which I see myself.

It is not me that has been chosen but my skin color, my gender, my age, my education, my socioeconomic bracket, my sexual orientation, my upbringing, my speech patterns, my vocabulary, my posture. I am my zip code and my books and the brand of my shoes, now sitting alongside the other jurors and their complementary demographics.

In this room full of strangers we are dominos: like first pairs with like. The least dissimilar pieces connect over the obvious and arbitrary. If our identities possess any intricate craftwork, it has been blurred and obscured and forgotten. Now we are distracted by the markings on each other’s faces, by the brushstrokes that have painted over all of our messy and complicated humanness.

Some archetypes have been double-cast along racial lines, as though the attorneys were assembling sets of salt and pepper shakers and lining them up on the formica: Retired utility worker, black; retired utility worker, white. Educated lesbian, black; educated lesbian, white. Young professional female, black; young professional female, white.

One juror doesn’t talk to anyone. He can’t be older than 20. He’s lanky and dark and sits in a corner facing away from the rest of us. When we make introductions, he says he lives right by the street where the crime went down. He pulls his knit hat down over his face, covers it with headphones, and closes his eyes.

The rest of us find one or two others and begin to cluster.

I select for myself the aerospace engineer who teaches science at a Quaker school. She has cropped hair and talks about her girlfriend and their dog and game nights with friends. We both have terminal degrees, we both have taught, we both are in our 30s. And I guess our skins are the same shade, but that’s not why I sought her out. I don’t think that’s why I sought her out.

#3

Here are the facts of the case. A girl in her mid-20s was groped outside the train station by a man who smelled of alcohol. She shoved him and ran away. His gait was unsteady. The sun was setting; the girl was coming home from working a shift at a restaurant downtown. The assailant found her again several blocks later and threatened her life. He grabbed her hair in his fist and pulled her behind a house. He pushed her into the dirt and grass and held her down.

He punched her torso. He hit her face and covered her mouth so she couldn’t call out. He broke her glasses. He might have done more but two girls from the neighboring college ran to the girl’s aid. They took her, shaking, into their home until the police arrived. The assailant was found stumbling around the neighborhood and was apprehended by the police.

#4

I do not condone criminal behavior except in extreme circumstances and certainly I don’t condone violence. Still I try for empathy.

The defendant is 23 years old and lives in 400-square-foot apartment shared with his brother, his mom, and his nana. He does not work. His mother cleans an office building. His nana is dying.

When I was 23 years old, I stood in front of a college classroom halfway around the world and led conversations about books and words. I lived in a university flat provided to me by the school. The fear of the students’ judgment bloated the hour before every class with anxiety. The students had no real power over me, but I was afraid of disappointing them, afraid that my teacher persona wasn’t enough to inspire.

The defendant faces charges of felony threats. Kidnapping. Misdemeanor sexual abuse. Assault. Destruction of property.

I wonder what emotions bloat the hours before he returns to the courtroom. I wonder what he feels standing in front of this jury of his peers.

#5

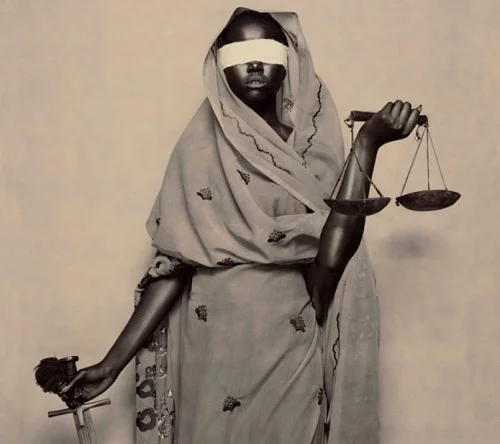

It’s more than an issue of race. Defendant, victim, judge, and both counselors would check the same census box, but that is no equalizer. The defense attorney speaks of gradations, of mocha and brown and black and blue black, and I wonder what possibly this has to do with his innocence or guilt. We aren’t discussing wood stains. If we were, she would be a russet, a rosewood. The defendant’s would be darker than the victim’s. But we aren’t discussing wood stains.

#6

We do not know if he has committed the alleged crimes but already he is guilty.

He is guilty because he’s sitting there. In that corner of the courtroom, where the jury box can stare him down. Where his hands are cuffed when he enters. Where an armed man shifts his stance whenever he rises from his seat. Seeing him sit day after day confirms something, grants us a certain kind of permission.

He is guilty because his defense attorney wears zebra stripes and red patent pumps into the courtroom and punctuates her claims by flipping her hair. Because she uses the word "coinkydink" and points to an image of a rabbit and a cat with the same marks on their fur to demonstrate its meaning.

He is guilty because his face has been tattooed. The skin on his right temple: six stars. His mother’s name on his neck. His dreadlocks cast his face in perpetual shadow.

He is guilty because of the stories we invent to explain his flat expression.

And is he guilty because he never learned to spell his name.

#7

The court record will show the defendant’s name sometimes opens with a Kwand sometimes with a Qu- . Which one is correct, the clerk asks. He shrugs. Which one is on your birth certificate. Can you spell that for the stenographer. He shrugs, he shakes his head. His eyes are large but not ashamed. His lawyer coaxes him, use your words.

What must it feel like to not possess a term for self. The uncertainty of letters, the floaty haze of language. To not know the sequence of your own syllables seems like a form of homelessness. Would I walk more actively through the world if I had no means of committing it to paper? Would I do more if my pen could not say?

They release us for lunch. I walk past a clique of government structures toward the unbuttoned city blocks and urge my eyes to blur the curve and swoop of text. The sidewalks are lined with colors and logos, with smells and footfalls and frozen air. It is February. My felted wool gloves scratch at my palms.

I have traveled to places whose language is foreign to me. This is a kind of illiteracy. And yet I know it cannot compare. When stranded in Budapest, I could consult books and decipher patterns in the city’s fluorescent lights. I could string letters together like beads on a chain, stringing and restringing until something meaningful emerged. When I was a child, someone must have handed me tools I needed, told me where to gather beads and how to cut chain.

#8

Even my imagination cannot grant me entry into this boy’s experience. My imagination is full of words he cannot spell.

#9

Writing this is not easy because I know the story doesn’t belong to me. Who then is its rightful owner?

This is the victim’s story but she has spilled her words many times already. People have listened; it is enough, she even said under oath she was exhausted by the retelling.

This is the defendant’s story because, guilty or innocent, he could never tell it himself. No one ever handed him the tools.

This has become my story because there’s a man in prison and I am one-twelfth the force that sent him there. I divide his nine-year sentence by the number of jurors. I am responsible for 270 days of his incarceration. The weight of this on my conscience is not eased by the likelihood that he committed these crimes. I want to find the other jurors and ask them. I want to know if the weight of enforcing a broken system pushes down on them as well, if the discomfort of the jury room has seeped under their skin, if like a tattoo it has not budged in the days and years since.

This is not my story but I have the ability to tell it. I can daisy-chain the moments that both shaped my perspective and prepared it to be expressed. Grade school teachers who impressed upon us the importance of community and service and civic engagement. A lawyer uncle who describes his court cases at holiday visits. Parents who have made a profession from the study of human thought and behavior.

This should be everyone’s story because our shared discomfort is a plea. Some of us never experience it. Some of us live there. And there are no amplifiers in that place. Call out and call out and call out and all we hear is silence. The discomfort reminds us to pay attention to that silence, to not trust it is as empty as it sounds.

#10

The kid who turns his head to the wall and closes his eyes is the only juror who wants to acquit the defendant.

I just got a feeling he didn’t do it.

The foreman nudges for more. If we were discussing wood stains I would tell you the foreman would be something in the maple family. Instead I’ll tell you she’s a she. Okay. What in the facts we’ve heard during this trial support the idea that he didn’t do it.

I know a guy. Buddy of mine. He got charged with stuff, a girl said he did something but he didn’t do it. He got locked up.

We look again at the photographs offered by the litigation technology unit. Of course the defense has no technology unit to collect evidence for their case. They have a story about coinkydinks and a picture of a rabbit and a kitten with similar spots on their fur.

If this kid’s buddy had a technology unit available to study his innocence, what then. If the defendant had one.

#11

I am a young white woman who has been given a lot of chances sending to prison a young black man who’s had no chances at all.

And yes: Attacking a woman is a despicable act. She did nothing; she didn’t deserve it.

To say he’s had no chances is not an assumption. It is either a truth or a tactic of the defense. And what did he do to deserve it.

#12

We’ve decided, yes, he is guilty. It’s been three hours of deliberation and submitting paper questions to the judge. Even the kid has conceded; he does not think we’re right, but he wants to leave this room. He raises his hand for a final vote. Fine. Guilty.

But here are my doubts, reasoned and reasonable. I have jotted them in my juror’s notebook as though perhaps they’ll be seen:

I doubt any of us, but for the kid in the corner, are truly this man’s peers.

I doubt the efficacy of a lawyer who is at best a terrible joke and who makes the defendant the punch line. We laughed where we should have balked and when she dropped her stack of papers on the floor for the ninth time we let it color our opinion of her client.

Here, then, is my most reasonable doubt, the best I can muster. I arrived at the courthouse 8:30 on a Tuesday morning to contribute to this process of serving justice. Every day for two weeks, I sat and listened and played Juror #7 with conviction and charm.

Would it have made a difference if I stared at the carpet instead of the biases of experience. Would it made a difference if said different words. The process was in place long before me and will remain long after. I arrived at the courthouse and sat and looked and looked for holes in which to insert my voice, but there are no amplifiers in this place. The carpet absorbs all sound.

Jennifer Clements is a writer and editor based in Washington, DC. Her work has been featured or is forthcoming in publications including Barrelhouse, Hippocampus, WordRiot, Psychopomp, and The Intentional. She is a prose editor of ink&coda and a staff writer for DC Theatre Scene. She holds an MFA in creative writing from George Mason University.