BY MAGGIE MAY ETHRIDGE

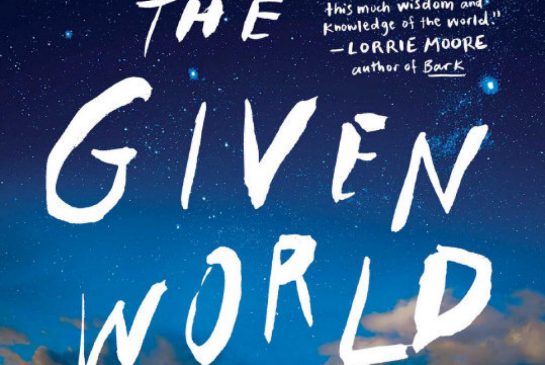

The Given World by Marian Palaia opens time capsules like Maruschka dolls: First, it is late 80’s in Siagon. Swiftly, it is 1968 Montana, and Riley, the protagonist, is a little girl whose world is about to be blown open.

Marian Palaia writes Riley as a casualty of the Vietnam War. After Riley’s idolized, older brother goes permanently missing in the tunnels of Cu Chi, Riley remains locked in the bubble of her home with her parents. Life drains from the home as the months and years go by as the body of the family slowly dies next to the ghost of their oldest son. Riley’s fall from the roof—foreshadowing the falls to come—introduces her to morphine, and her hunger for escape is met with an outlet.

The next fall: a pregnancy. Riley leaves her infant son with her parents and spends the next 30 years wandering San Francisco, briefly touching everything she encounters with an attentive, wary mind, never embracing anyone or anything. She meets and walks alongside a number of walking wounded: Primo, the half-blind vet; Lu, a cab driver with an artistic heart; Phuong, a Saigon barmaid; and Grace, a banjo-playing girl on a train, holding her grandmother’s ashes on her own journey. All are hiding in plain sight.

Her removal and appraisal are slowly eroded by the scraping of drink, drugs and sex against her outer shell, and the lull of the years, each collapsing on the next until Riley is far enough away from the moment she learned her brother was missing. Once she is far enough away, she can return to the wound; following her brother’s footsteps, she visits Vietnam. Only then, Riley attempts sobriety.

Marian Palaia’s sentences are excellent in drawing out Riley’s inner experience of the world—highly observant, intelligent, but flattened and removed—allowing us to experience the colossal damage of loss that the Vietnam War brought to Riley’s family. That Riley’s brother disappeared, that the family never had a body to mourn, is an echo of Riley’s own internal life—one foot in, one foot out. No proof of death, no proof of life.

A grown son and ailing parents meet Riley as she awakes; I appreciated the way Palaia draws Riley’s story to a close—not in a neat bow, but in an outline of possibilities, a sketch of what is possible if Riley can continue to emerge from the fog of disbelieving grief, and into the arms of an imperfect, but living world.

Maggie May Ethridge was born southern Mississippi and has lived in San Diego most of her life. She is a community/social media manager and writer and poet. She writes for Bustle.