BY MADELEINE BARNES & KELLY GRACE THOMAS

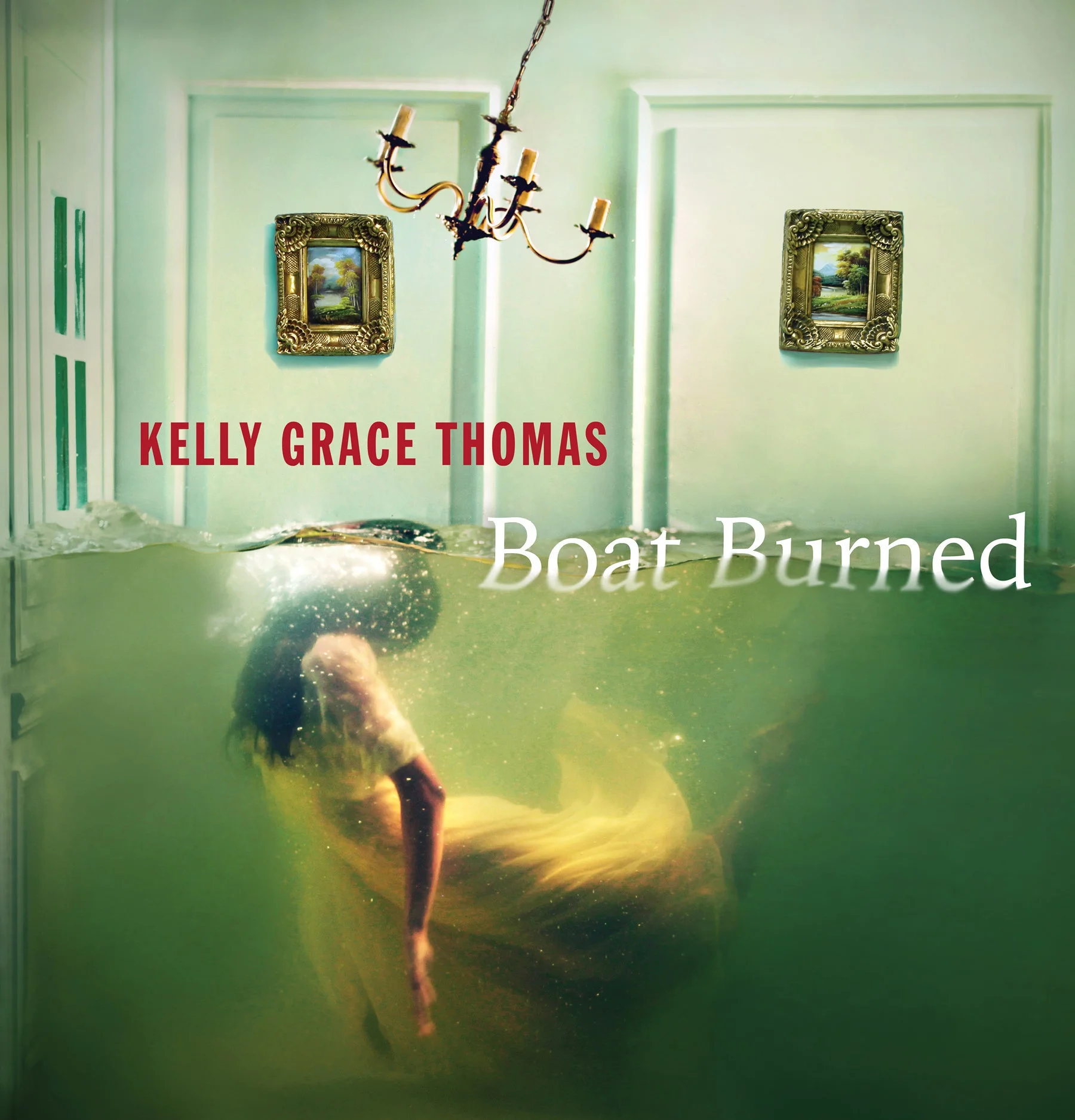

Boat Burned by Kelly Grace Thomas

YesYes Books, 2020

110 pages, $16.20

In Boat Burned, Kelly Grace Thomas’ debut poetry collection (YesYes Books, 2020), we join a perceptive, vulnerable, authentic speaker in confronting and untangling the effects of generational and collective trauma on the body. In “Vesseled,” the first poem in the book, she writes: “He boarded me. I burned.” This truth is one she “can’t throw overboard,” and the ocean is her witness as she observes what remains of her.

Thomas’ poetry invites us back to the sea, and its stillness invites us to reflect on tensions that cast shadows over our lives: chaos and order, self-punishment and worth, violence and liberation, trauma and recovery. The speaker desires “to divorce the earth,” and studies leaving “like a chart.” For Thomas, family is a synonym for “horizon.” In the speaker’s family, three women privately struggle with eating disorders but never talk about it—she longs to leave, but struggles to find the exit ramp. It is critical for her to go beyond the horizon, and through interrogations and deconstructions, she attempts to recover. She endures the mangling effects of self-surveillance; secrecy is a lack of oxygen.

Drowning remains a possibility, but the third and final section of the book reveals the beginning of the speaker’s journey toward a reconciliation with her body: “Body, why can’t I remember you / right? I know you’re no life / boat.” Here, the narrative transforms into one of triumph, asking us a critical question—when we are at sea, how do we want to drift? What structures and pressures make this choice ours and not ours?

In writing this book, Thomas endeavored to “recover from womanhood,” and in this interview, she reveals more about what this means to her. She also offers words of encouragement and gives thanks to poets who write about similar themes. She reminds us of all the ways that capitalism profits from our inability to love ourselves; self-love is a life-sustaining skill that no one teaches us. Reading her book, I was reminded of Alice Walker’s assertion that “telling and honoring the truth carries the possibility of transformation and delight.” Thomas uses both metaphor and direct language to deliver her truth. Her candid poetry strikes back against the layers of stigma, silence, and misinformation that compound trauma. “They can’t sink us,” she writes, “if we name ourselves / sea.”

MB: Boat Burned (YesYes Books) openly examines private struggles with trauma and the body. You write with incisive clarity and strength about conditions that thrive in secrecy and are still stigmatized, even in literature. In “Where No One Says Eating Disorder,” you write about a family in which everyone is struggling privately: “When I was young, I pretended / we weren’t sick. Three women. / Three rooms.” We watch the woman in this family struggle in silence and isolation. The poem concludes, “We were so hungry / for anything / to love us back.” Why was it important to you to include your family members’ experiences of trauma and disordered eating in this book, real or imagined?

KGT: Plain and simple: I had to. This story, this struggle, is so much bigger than me. That was important for me to recognize share with readers. So many elements of disordered eating are shrouded in isolation and shame, and that’s what the disorder feeds on, how it survives. Eating disorders are sustained by silence. The less we talk or write about it, the sicker we remain. It took me years to admit that I was punishing myself and trying to control the world around me with food.

Carolina Public Health Magazine states, “A shocking sixty-five percent of American women between the ages of 25 and 45 have disordered eating behaviors, according to the results of a new survey sponsored by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and SELF Magazine.” That means roughly every two out of three women struggle with this. There is so little education and prevention, let alone conversation. I wrote this poem to show readers that this disorder is one that affects many. Growing up, every woman in my household had an eating disorder. We did not admit this to anyone, not even to each other, until almost twenty years later. We spent two decades suffering in isolation. The important question is: Why?

I’d always wanted to write openly about body image issues and eating disorders. This plagued me, but I worried that writing about my body made me a cliché. Women have been programmed to equate their appearance with their intrinsic worth. Industries thrive on women’s insecurity. The less we love ourselves, the more companies profit. This narrative is changing, but progress is slow because these conversations are often had in private. It’s time to start figuring out how we can help—it’s time to heal. It felt irresponsible not to contextualize my own eating disorder within my family—all of us were suffering, yet felt so isolated.

MB: You’ve spoken in the past about metaphor, and this book does a wonderful job of using metaphor to describe a struggle with the body. You write, “I thirst for shelter / I have no faith in. My body: a church / where no one prays.” We watch the speaker “confuse body / for boat.” A mother “unzips the body. / Passes it down. You also show us that there are no metaphors for some aspects of living with an eating disorder. In “No Metaphor For My Mouth,” you write, “I have no more lines memorized. // Nothing dainty // to make you // weep.” Did you make conscious decisions about balancing metaphor with direct description in this book? Recovery-wise, what is the benefit of setting metaphor aside and facing the reality of an illness, however stark?

KGT: What a great question. I don’t think this balancing was conscious, but as I wrote, my writing became more direct. In “Where No One Says Eating Disorder,” it was important to me to depict silence before the first line. In my view, metaphor makes hurt accessible. Metaphor gave me the key to enter the house; it also gave me the hammer. Once inside the house, I could stare at the walls and try understand why I built them before tearing them down.

When I first started to write poetry, I questioned lines that spoke directly. I thought that perhaps they lacked the musicality or depth necessary to capture pain. I have come to realize that there is nothing more vulnerable than letting a simple, direct statement hang in the air, unadorned. It lets readers look pain in the eyes.

MB: In the incisive poem “In An Attempt to Solve For X: Femininity As Word Problem,” you write, “The difference / between shame and guilt is showing / your work.” Shame and guilt continually provoke the speaker, who fights to “turn this shame to sanctuary.” In “At The Bar My Friend Talked of Bodies,” shame is a toxin: “No stomach can digest / shame: a congregation // of rocks. Patient in a / poisoned well.” Does writing play a role in mitigating or coming to terms with shame?

KGT: Yes, writing is an investigative path out of shame. We can’t conquer what we don’t understand. Just like fixing a crack in a foundation, I needed to find the first fracture. When compiling the collection, I noticed that many of my poems speak directly or indirectly about the shame I felt about womanhood, which in turn was linked to my body and perpetual guilt. I have listened closely to the world while taking notes on why shame can sometimes feel like an appropriate response to what the world tells women.

So often I am quick to swallow blame, and the lines you referenced are an attempt to show the reader I know what it is like to live as an apology. It was a chance to call myself out on the page, publicly, directly; it was a promise to write myself stronger. Boat Burned let me identify the guilt and find a path out of the shame. By the time I finished the book, I was no longer ashamed of who I am.

MB: In a recent interview published in [PANK], you spoke about water: “Water will always be stronger than boat. Stronger than gender. It is the hands that hold us, the mother that covers us, the power and grace, that allows us.” What is the relationship between water, control, fertility, and recovery in your work?

My relationship with water is one of the most important relationships in my life. There is a quote by Isak Dinesen: “The cure for anything is saltwater — sweat, tears, or the sea.” This is one of my core beliefs—we came from the sea, and my body and soul are always trying to return.

Growing up, there was a lot of adventure and uncertainty in my life. There was bankruptcy, divorce, eviction, addiction, and of course, eating disorders. The water felt like the only thing that could hold me without making me feel like a burden. I spent a lot of time on boats, sometimes in the middle of nowhere with nothing to do but stare at the sea. Its steady quiet always returned my gaze, pulled me into the peace of a blue horizon, and challenged me to sit with what I was running from. I couldn’t have accessed this stillness without water.

I use water to think about the ebb and flow of life. The ocean holds an understated power. It breaks and breaks, yet still survives. Its breaking is inevitable. We cannot change or influence the ocean; we cannot prevent low tide. The ocean is not concerned with us, and I love that. I reach for water for strength, and to heal whatever is breaking within me. There is so much healing to be done, and water reminds me that healing and recovery are possible.

MB: Eating disorders are still deeply misunderstood and stigmatized. In what ways did you choose to push back against stereotypes or tropes surrounding eating disorders in your writing?

KGT: It is counterproductive to talk about shame and without mapping the origin. Women especially have been programmed to hate their bodies. In The Self Love Experiment by Shannon Kaiser, I read that a whopping 90% of women hate their appearances. This breaks my heart daily. Eating disorders are not only stigmatized but glamourized. In the media, eating disorders are portrayed as a phase. There are so many after-school-special-like tropes I wanted to avoid in my writing: the teenager working out until she passes out, the bathroom scale with its cold steely gaze. These tropes aren’t inaccurate—but so often, movies on this subject are made by people who don’t suffer from eating disorders, and they wind up creating caricatures of sufferers’ pain. Plot points can occlude the real story. Sometimes, a character’s eating disorder is “cured” in an episode or a season.

After 20+ years, I still suffer from ED-related thoughts. Some people who have eating disorders think they are fat, which can lead to feelings to worthlessness, because this country and the media has linked body size to worthiness. We have also been told that shame isn’t sexy, so we punish ourselves further for feeling shame, which buries us further in stigma and silence. At 39, I am still struggling with the relationship I have with my body, which will continue unless I do the work of active unlearning and reprogramming. I am learning not shudder at bad lightning or inquiries about my weight. I want to show people that eating disorders are not rooted in vanity. They are rooted in feelings of unworthiness—so many feel unworthy love and so much more.

Like so many people, I felt unlovable in the body I was in. I wanted to feel like I was worth something, and when I developed an eating disorder, I felt like it was making me worthy of the love I sought. When I would lose a lot of weight, I got lots of positive reinforcement. The problem is that this is an illness. It took me forever to admit that.

MB: Are there any writers who deal with the body in their work in ways that influence you? Conversely, is there anything that frustrates you about other people write or talk about eating disorders?

KGT: There are so many poets who write about the body beautifully. One poem that comes to mind is Jennifer Givhan,’s “I Am Fat, & When You Read this Poem, You Will Be Too.” This poem should be required reading. I also think of the book Helen or My Hunger by Gale Marie Thompson, and To Know Crush by Jennifer Jaxson Berry. Courtney LeBlanc also writes about the body, disordered eating, and body dysmorphia. These poets are outstanding. It frustrates me when people view body image issues as temporary, like a haircut. I’m reminded of Lucille Clifton’s poem, “i am running into a new year.” She writes: “it will be hard to let go / of what i said to myself / about myself / when i was sixteen and /twentysix and thirtysix / even thirtysix.” At 39, I am still trying to heal, still trying to let go and forgive. People don’t understand that this is a long road.

MB: Section IV, the final section, has so much momentum—poems like “How to Storm,” “New/Port,” and “The Only Thing I Own” show us a speaker who finally allows herself to rage. She finds motivation to recover: “There is a part of me / worth keeping.” She implores the body: “Let’s hold each other // honest as wind.” In “Boat/Body,” you write, “I will not kneel / for a man’s affection,” and “They can’t sink us / if we name ourselves / sea.” Can you speak to your experience of writing section four, and the role of anger in both writing and recovery?

KGT: The last section of this book, which I view as a nod toward acceptance or forgiveness, was the hardest section for me to write. While in the middle of writing Boat Burned, I told a young woman friend that I was writing a collection of poems “to try and recover from womanhood,” and “to teach myself how to love myself.”

She asked me if it was working. I was honest and told her it wasn’t. At that point, I wasn’t sure it was possible to recover from womanhood through writing. But I knew that I couldn’t finish this collection in the same place I started. I needed to burn the boats that brought me here, and to walk away and never look back. So I kept on writing and revising until something inside me changed. Silence and subordination were no longer compelling.

In every Speilberg movie, you never see the monster until the end. When we can’t see it, the monster remains terrifying. Writing the last section was about confronting the monster to make it less menacing. The more honest I got in these poems and the more I sent them into the world, the less scary these monsters became. When I am too afraid to address something in my life, I need to put it in a poem. A poem is the first step toward confrontation, the first brick in the road to recovery. This book took about 3 years to write. I am no longer the person I was when I started writing it. I had to chase the why, to unpack every lie I swallowed, to take off the sadness that wore me like a dress, before I could heal.

MB: You run a series called Body of Art where you talk to other poets about the body and its role in their work. Are there any takeaways from your conversations with other creators that stand out to you?

KGT: Oh my gosh, there are so many takeaways, the biggest one being that no one teaches us how to love ourselves. I believe that there is a direct correlation between loving oneself and leading a fulfilling, liberating, and conscious life. We learn Algebra and the Periodic Table, but no one teaches us how to love ourselves. Every day I study and practice how to be kinder gentler toward myself. Like so many around me, I need more practice. It shouldn’t be such a struggle, but it is.

MB: Are there any words of encouragement that you might offer to a creative person who is struggling with an eating disorder? What you would tell someone who is on the verge of seeking treatment, but hesitating and doubting the value of their voice?

KGT: I would tell them that there is another side, but there will be a crossing over within yourself—you will need to decide that recovery is worth it. You will have to unlearn everything the world has told you. I would also shout from the rooftops: Write. About. That. Shit. I remember when “Where No One Says Eating Disorder” was published. I was flooded with messages from so many women saying things like, “You have no idea how much I relate to this.” Or “Thank you, no one ever talks about this.” Women ages 18-65 thank me every time I read a poem about an eating disorder.

Whoever needs to hear this: You are not alone. You are not your reflection. You do not need to be what the world tells you to be. Talk and write about what you are going through. There is freedom in language. If you need someone to listen, find me on social media. I’m here if you ever want to talk about the other side.

Kelly Grace Thomas is an ocean-obsessed Aries from Jersey. She is a self-taught poet, editor, educator and author. Kelly is the winner of the 2020 Jane Underwood Poetry Prize and a 2017 Neil Postman Award for Metaphor from Rattle, 2018 finalist for the Rita Dove Poetry Award and multiple pushcart prize nominee. Her first full-length collection, Boat Burned, was released with YesYes Books in January 2020. Kelly’s poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Best New Poets 2019, Los Angeles Review, Redivider, Muzzle, Sixth Finch, and more. Kelly is the Director of Education for Get Lit and the co-author of Words Ignite. She lives in the Bay Area with her husband Omid. www.kellygracethomas.com.

Madeleine Barnes is a doctoral fellow at The Graduate Center, CUNY. She is the author of You Do Not Have To Be Good, (Trio House Press, 2020) and three chapbooks, most recently Women’s Work (Tolsun Books, 2021). She serves as Poetry Editor at Cordella Magazine, a publication that showcases the work of women and non-binary creators. She is the recipient of a New York State Summer Writers Institute Fellowship, two Academy of American Poets Poetry Prizes, and the Gertrude Gordon Journalism Award. Her criticism has appeared in places like Tinderbox Poetry Review, Split Lip Magazine, and Glass: A Journal Poetry. www.madeleinebarnes.com.