BY TINA V. CABRERA

I have always been drawn to black and white photos more so than color. I know the basics of color theory: black is the reflection of no color and white is the reflection of all colors and the colors we perceive are a matter of how much of the color present in light is reflected versus how much is absorbed. But theory does not help me answer these aesthetic questions: What is the appeal of black and white photography? How do photos, whether in black and white or color, relate to the stories we tell ourselves about the world?

When I watched the documentary on Brazilian social photographer Sebastiᾶo Salgado, I was immediately drawn to his representations of Genesis captured in black and white. To my delight, I received his long series of photo essays of that name as a gift the following Christmas. Hundreds of glossy photos span the world’s great oceans and continents across great expanses of time. The book is divided into five sections, beginning with "Planet South," which refers to the ecosystem of Antarctica, and ending with "Amazonia Pantanal," the Amazon region.

In the Foreword, Salgado says that in beholding "a world unchanged over millennia," he "felt privileged to watch the endlessly repeated cycles of life." In this one statement, he indicates a relationship—albeit indirectly and subtly—between black and white photography and the passage of time and with the cyclical nature of the world simultaneously. His photos at once capture the striking immutability of nature over millennia, yet ironically, it is the unchanging nature of the world that repeats. Time moves on and memory fades, rinse, recycle, repeat. Black and white photographs can convey a sense of the past and of timelessness simultaneously. Perhaps that is why Salgado chose to take his photos of a repetitious world in black and white. Black and white photos are closely linked to the historical, yes. Black and white images reassure me (even if artificially) that what I am looking at fully belongs to the past, to history. But there is a bridge from the past to the present and even the future. For example, Salgado’s photos of tribesmen living in parts of the earth relatively untouched by civilization present a portion of the Genesis of human history, and yet this tribe’s way of life still exists in the present. One speculates on whether this untouched world will remain so for much longer into the future, considering the ramifications of globalization.

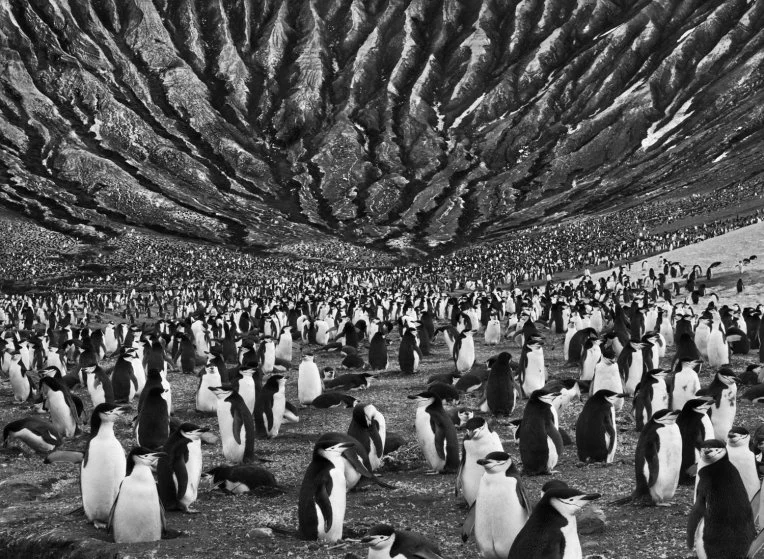

Still, if life already lived is best represented by black and white photography, life occurs in color, if you will. Color photos convey a sense of immediacy. Yet, just as the past seeps into the present into the future in black and white images, a bridge exists between these and color. When I see an object captured in black and white, I cannot help but think of the relevance of the image to the current moment. When I look at the photo of an iceberg in the Antarctic Peninsula topped by a stormy sky, and look through the large keyhole shaped opening to the other side, or the aerial shot of thousands of penguins spread out on the land expanding from a tiny volcanic island, I imagine the passing of millennia and the relentlessness of the cycles of life. Then when I think of how the present is always already becoming the past, the future eternally becoming the present and past, I sense the enigmatic connection between photography—whatever hue perceived by the eye—and time.

Seals & Penguis by Sebastiᾶo Salgado

Description: I love the juxtaposition of the individual and the community. The lovely seal in the foreground, and the group or mob in the background.

Borges claims that time is circular. In this conjecture, he includes Marcus Aurelius: "any time span – a century, a year, a single night, perhaps the ungraspable present – contains the entirety of history." How can a single night contain all of history, as equally as a century can? Borges explores the idea of history as eternally returning. In doing so, he quotes among others, Lucilio Vanini: "Nothing exists today that did not exist long ago; what has been, shall be; but all of that in general, and not (as Plato establishes) in particular." What he means is "that all of mankind’s experiences are (in some way) analogous," that is, generally universal. In this way, a single night’s occurrences have already happened in some manner in the past, and return repeatedly. Applying this theory to photography, you can look at one photo of one moment and in effect see all of history. But not just history, the future too. Borges refers to Marcus Aurelius again: "To see the things of the present moment is to see all that is now, all that has been since time began, and all that shall be unto the world’s end." Even the most negligent photographer then, can capture eternity by the stroke of a finger, through a single photograph.

RELATED: Photo Essay: Harvesting Moonlight from Our Bodies

While a machine like a camera has the capability of capturing a single moment permanently and lucidly, a human being comes equipped with a brain that can contain and retain images, yes, but in the flawed form of memory.

I have a peculiar, recurring memory that taunts me. At first, I am not sure whether what I am remembering is authentic memory or the remnants of a dream:

My sister and I sit across each other, hands interlocked, knees bent, her larger feet pressed against mine. She leads the pushing and pulling and for a little while we work like a well-oiled machine. Then she lets go of my hands and I fall back. When my head crashes against the floor, the thud creates ringing in my ears. I see in tones of black and white and gray. I close my ears with my hands to make the ringing stop. Papa chases my sister around the house with me tucked under one arm, and holding the bunk bed bar with the other. I hear muffled voices, my sister crying, my father yelling, threatening to beat her with the bar.

I am on the phone with my sister. I bring up (timidly, hesitantly) the incident from our childhood, and my sister remains silent for a brief time. She then says she thinks she remembers, and that of course, whatever happened, she didn’t mean to hurt me. She asks if I remember something else, how she often used to lock me in the garage when I was little, and leave the door locked until I cried, and then she would listen to me cry a little while, and when it got unbearable (the sound of my cry?) only then would she unlock the door and let me out. How it felt good to console me afterward. When she tells me this story, I remember vaguely, and I feel a dull, familiar sadness, maybe from the memories of her carelessness and cruelty, maybe because I’m still not convinced of the veracity of any of these childhood memories. Feelings strengthened by the sheer act of trying to remember. My sister’s memory seems to compliment mine for the most part, but still, for some reason, I doubt. I hover in that purgatorial state of uncertainty because of the uncertainty of memory.

Why am I am drawn to black and white photography? Perhaps because, unlike memory, black and white photos evoke a sense of reliability. They are conduits of the past, concrete objects one can return to for a sense of security that what one perceives or remembers is real and true. All this, that is, before subjecting the photographic object to the added powers of narrative, of story.

Tribesmen by Sebastiᾶo Salgado

Description: The sense that these tribesmen, evoked by the foggy black and white appearance, are untouched by civilization—frozen in time.

Tina V. Cabrera earned her MFA in Fiction from San Diego State University in 2009. Her essays, fiction, and poetry have appeared in or are forthcoming in journals such as Pleiades, Hobart, Luna Luna, Quickly, Crack the Spine, Big Bridge Magazine, Vagabondage Press, San Diego Poetry Annual, Fiction International and Outrider Press. She has presented critical work at the Northeast Modern Language Association (NeMLA) in New York and Pennsylvania, which has been published in print and online. You can visit her writer’s blog at www.cannyuncanny.wordpress.com/.