BY JOANNA C. VALENTE

Rebecca Nison is one of those people you want to hate a little bit, because she's just good at everything. Being a poet and a painter, while not completely unheard of, is pretty unusual if you're actually talented at both. And she is--she's proved it in her new book, If We'd Never Seen the Sea, which was published by Deadly Chaps Press at the end of 2015.

I was eager to talk to her, as a poet and visual artist myself, about her process and how she so seamlessly weaves both together:

JV: What came first—the pictures or the poetry?

RN: I consider this to be a sort of collaboration between a writer and a painter, both of whom happen to be me, or rather, different parts of me.

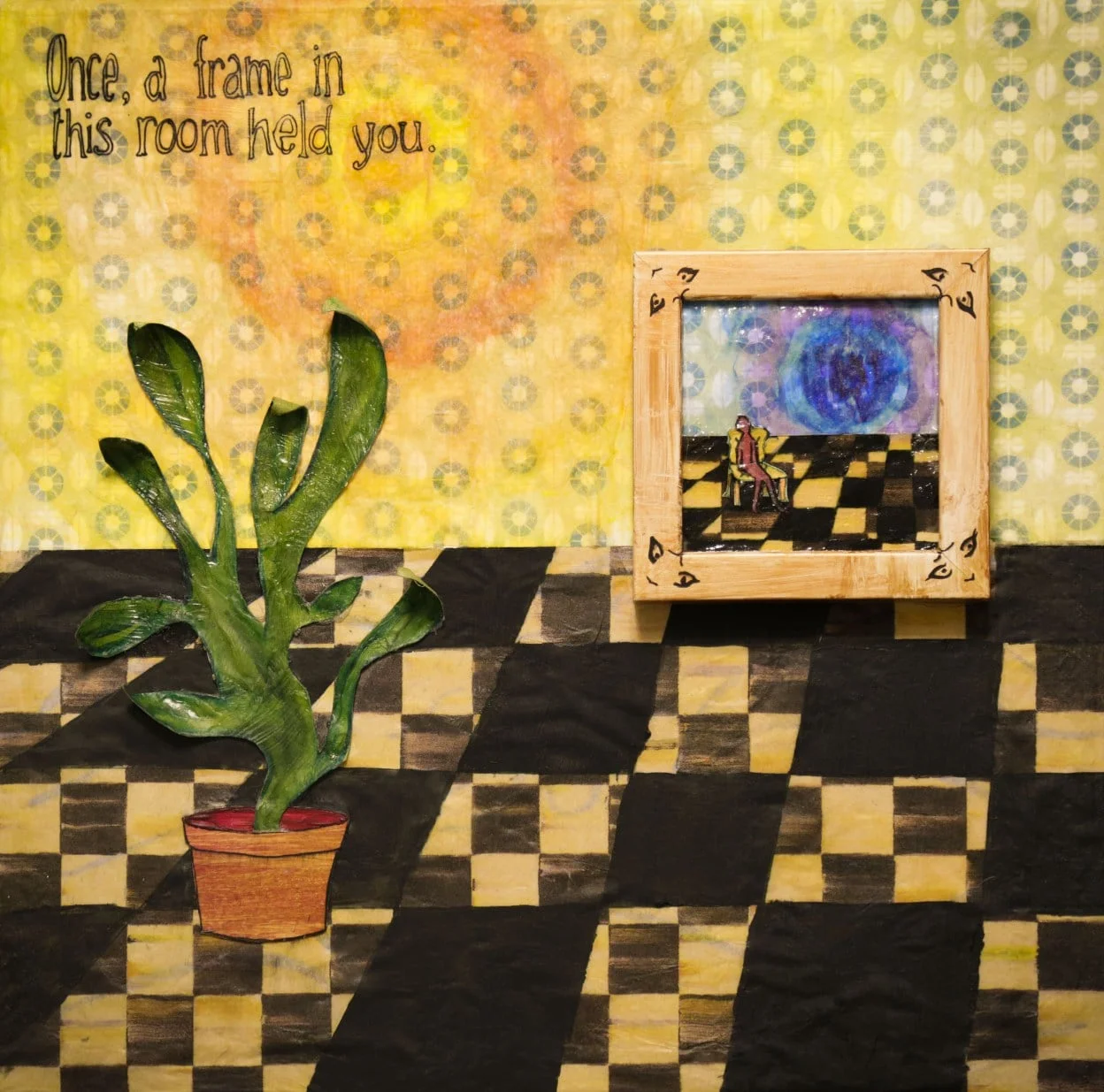

For the most part, I wrote the poems first, but when I got to painting, the art-making process triggered changes and revisions. The burning core of each poem endured from its start (as black ink on white paper) to its end (as a poem in paint), but I improvised as I went. The images were not meant to be pure illustrations of the text, and so, I needed to make room for the new meanings they brought to the table.

In an ideal situation, I think that’s what collaboration’s all about, be it collaboration with yourself or with someone else: opening your original intention wide and allowing for shift in order to find yourself someplace new.

The poems almost seem like reminders to the speaker, not to anyone in particular. Would you say this is accurate?

“...you’d be home by now” is intended for as universal a “you” as I know how to write. So yes! In the case of this poem, your interpretation is absolutely accurate.

The other two are a bit more specific, though.

“Upon Breaking Into Our Old Home, I Find the Furniture Changed” is addressed to someone who once shared a home with the speaker, and who no longer does. I know that’s ambiguous. It’s meant to be. The addressee could be a lover, a family member, deceased, alive, nations away, or in a different room inside the very home our speaker’s broken into. By confronting the space they once shared, the speaker’s confronting the loss of the “you.”

“Love Song for the Dying” is written from the perspective of two longtime lovers in first-person plural. Upon recognizing death is near for them, they choose to adventure rather than submit to their bodies’ mounting limitations. The speaker and receiver are merged into a single voice that blockades the outer rational world from invading the fierce little fortress they’ve made together.

Rebecca Nison

What were you listening to and reading and watching while writing this?

The first iteration of “Love Song for the Dying” was written almost ten years ago, and it’s evolved with me over the course of that time. Similarly, the text in “...you’d be home by now” was a culmination of reflections on home strewn about and jotted in notebooks over the course of many years. It’s difficult to winnow down what I was absorbing and devouring art-wise over the course of that time, but I’ll give it a shot and pluck out some highlights!:

Rainer Maria Rilke, Joseph Cornell, Waylon Jennings, Erik Satie, Vladimir Nabokov, Orlando by Virginia Woolf, Kelly Link, Orhan Pamuk, Twin Peaks, Frank O’Hara, Bianca Stone, Aimee Bender, The American Folk Art Museum

When working on the paintings for “Upon Breaking Into Our Old Home, I Find the Furniture Changed,” I listened to múm’s album, “Green Grass of Tunnel,” on repeat. That album is the musical version of the very headspace I enter when I paint. It makes the ‘commute’ from the trappings of daily life to an inner world feel like a cinch.

Have you heard of those gradual light alarm clocks that glow brighter, imitating the sunrise, so that your body feels as if it’s woken up naturally, without the dreadful blare of a typical alarm? This album was sort of like that. It eased me into inhabiting it.

How do you want the reader to ingest this book? How should they read it? It’s as once easy to digest, because the words and pictures meld together, but at the same time, it’s almost as if sensory overload is happening.

My baseline hope is that each reader forms the relationship(s) with the book that they feel compelled to. But my greatest wishes for the ingestion of this book are pretty simple.

1. Readers will feel intensely while experiencing the book

2. Readers will feel changed after experiencing the book

That said, I do have some more nuanced intentions. I’m toying with the tradition of picture books. Some of these images are deliberately childlike in their flatness and their color schemes, while the poems themselves (by that, I mean the words) are not at all childlike.

The paintings—playful in presentation, though not always in subject matter—are meant to invite you into this seemingly whimsical space. Once you’re inside, my aim is that the visual signals and the poetry will ping off of each other. I’m reveling in juxtaposition. The words complicate the images. The images recontextualize the words. The images are really meant to be a part of the poem and not separate from it: a substitute for the white space that’s usually so vital for a poem on the page.

If you feel sensory overload, any or all of the above may be why. I created this book as a sort of funhouse.

What part of you writes your poems? What are your obsessions?

I’m a fiction writer as well as a poet, and boy do poems come from a different place than fiction does. Actually, I think writing poems and painting are more similar for me than writing poems and writing fiction are.

I was so intrigued by this question, and so befuddled as to what answer I’d give, that I sat down to write a poem—and afterwards, I noted the parts of me that got involved. I’m not going to trim my list or edit it. I’m going to give you exactly what came out of my pen in the moments after writing. Here they are, the parts of me that write poems:

1. A part both frenetic and peaceful

2. The wanderer

3. The part that grapples, dissatisfied with logic

4. The part quenched by perplexity, ambiguous meaning, textures, senses

5. The funny little dancer (unselfconscious)

6. The high-speed train traveler, zinging from one end of the mind to another and back again

7. The opener

8. The luddite

9. The exhale

10. The part that wishes it was a musician but is not

11. The part that sings songs to Audrey (my dog)

12. The part that is glad to be human

13. The kid seeing a Jacob’s ladder toy for the first time. Only instead of marveling at the string and wood, I’m marveling at language, baffled, thinking, How’d it do that? How can words make all that happen?

And my short list of obsessions:

1. Doors, windows, and the thresholds between environments

2. Homes and their countless definitions

3. Houses and rooms: domestic habitats, the compartments we put ourselves in

4. The search for visceral existence, before articulate thought

5. Rebirth

6. Storytelling’s relationship to humanity

7. Dogs

Rebecca Nison's graphic poems explore the unnamable territory between image and word: a domestic wilderness both playful and perilous, where the familiar becomes funhouse and the funhouse becomes familiar.