BY MONIQUE QUINTANA

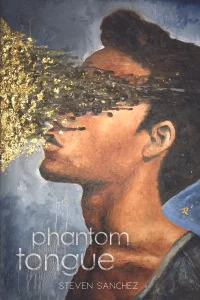

Steven Sanchez’s first full-length poetry collection, Phantom Tongue (Sundress Publications, 2018), celebrates all the dark joys and reverberations of growing up in a Mexican-American family as a queer brown boy. There are transgressions from and towards the body, metaphysical and literal borders, the crisis of the tongue, and the philosophical heart of lines that break and mend like bones. Here Sanchez shares a little about his journey from pen to book and back again.

Monique Quintana: Phantom Tongue explores and complicates tangible queer bodies. Some of my favorite books that do this are The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde and City of God by Gil Cuadros. What are some works you feel explore queer bodies in a compelling way?

Steven Sanchez: One that immediately comes to mind is What the Body Told by Rafael Campo—it was the first poetry collection I’d ever read by a Queer Poet of Color. Campo’s speaker describes his patients’ bodies with precision and tenderness—whether the speaker is dissecting a cadaver or using a scalpel to begin an operation, the speaker never once forgets the humanity of the person on the table—he actually imagines their stories, their lived experiences, and in the case of some of the unclaimed cadavers, he summons the people who love them. I admire how the poems in that book balance the violent and invasive nature of body examinations with empathy and compassion.

Some other books I love for the way they handle Queer bodies include: Sympathetic Little Monster by Cameron Awkward-Rich, Coal by Audre Lorde, Slow Lightning by Eduardo C. Corral, The Dream of a Common Language by Adrienne Rich, and A Map of Home by Randa Jarrar. All of these writers reclaim Queer bodies (and often Queer bodies of color) from prevalent and destructive cultural narratives. They access moments that feel like different types of Queer joy—joy rooted in the body, in desire, and in so many other ways considered “taboo,” ultimately retrieving and expanding their Queer subjects’ humanity.

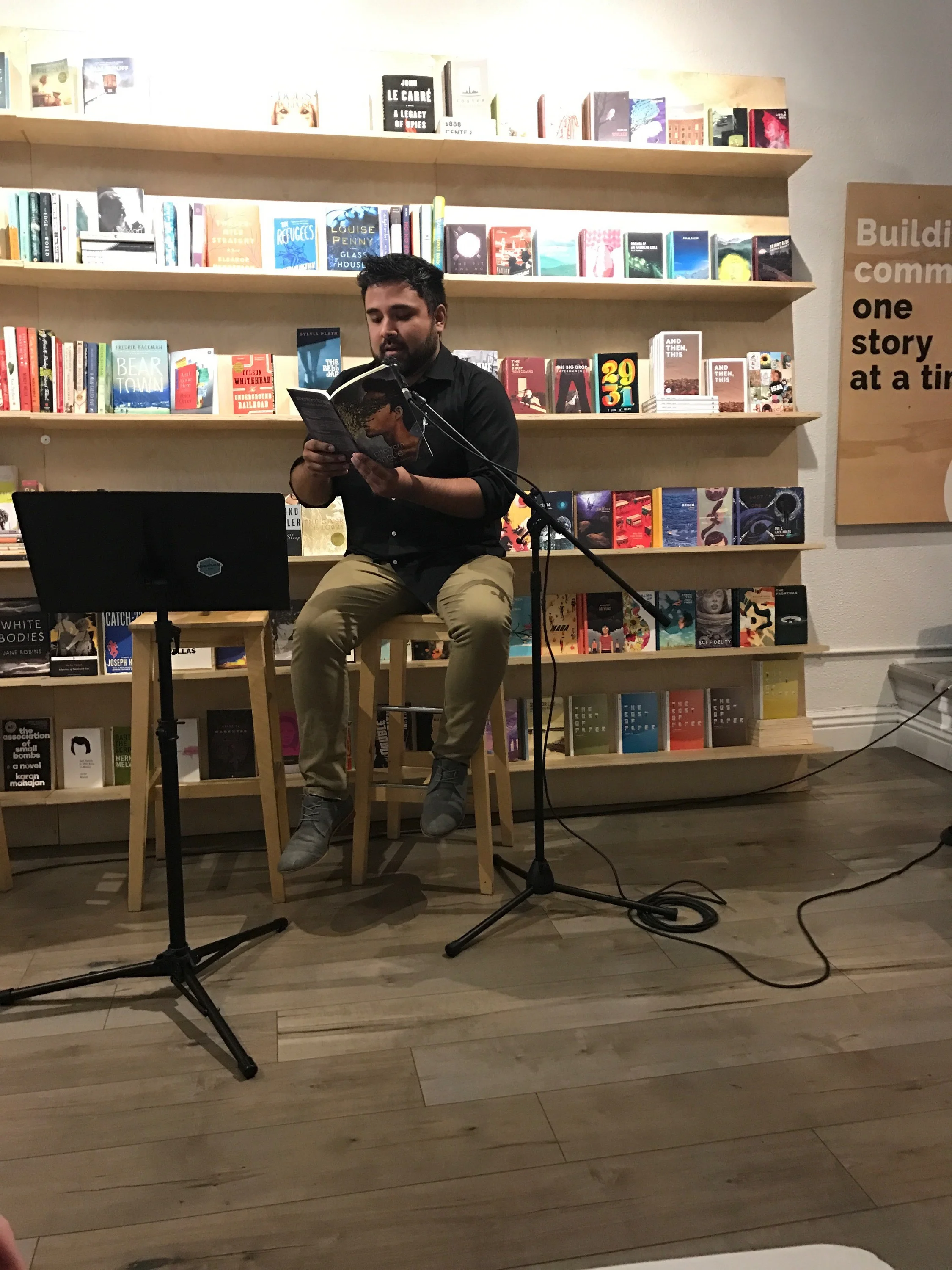

Sanchez

MQ: Your poems often discuss your pocho identity. Besides the content of your poems, how do you think your pocho identity informs your aesthetic, what your poems look and sound like on and off the page?

SS: I’m especially conscious of how Spanish enters my poems. While I don’t speak Spanish anywhere near fluently, I grew up surrounded by it—my family spoke it, my childhood church used it, and it was used in a lot of the t.v. shows and songs I heard growing up. So, even if I am not bilingual, bilingual texts still feel familiar to me, which made me wrestle with how (if) I should use Spanish. When I read one of my poems out loud that uses Spanish, I hear a tension, stress, and nervousness in my voice.

But, when somebody who knows Spanish, like my partner or some of my friends, reads one of those poems out loud, it sounds like my family or my old church. I don’t live in a monolingual world, my experiences aren’t monolingual, and I want my poems to reflect that. But, especially as a pocho, I don’t want to exoticize myself or commit cultural appropriation, which is why when Spanish does enter my poems, it’s through the voice of another person (such as La Llorona or a family member) rather than through my speaker. The only time my speaker actually uses Spanish is when they are consciously learning or struggling to speak Spanish. I guess I’m mentioning all of this because it affects how I use italics in my poems—I italicize dialogue instead of using quotation marks, so I’ve come to expect a certain degree of agency when I see italics and I’m hoping that anybody reading the poem gets that same feeling, even if they can’t pronounce the Spanish out loud.

MQ: You’re a fellow of both CantoMundo and the Lambda Literary Foundation. What are three of the most helpful things you have learned from applying for fellowships and attending workshops?

SS: When applying for CantoMundo and the Lambda Emerging Writers Workshop, they both required a variation of an artist statement explaining how my work fits in with each organization’s vision. Writing these statements forced me to really interrogate my own work—what is it, exactly, that my work is doing? What is it that I want it to do? How does my work fit in with, build upon, or challenge what’s happening in the Latinx and Queer writing worlds? What lineage(s) have nourished me? What lineage do I want to contribute to? I’d thought about these questions before, but having to actually sit down and articulate my thoughts in writing—in under a page, no less—forced me to answer them honestly and directly. The exciting part, though, is that the answers I gave for those questions are not the same answers I would give today—not to mention the answers I’d give today will probably (and hopefully) change in the future.

That’s something else that CantoMundo and Lambda taught me—marginalized writers are not monolithic and our own relationship to writing will continue evolving (our meaning individually and as a community). Sure, there might be themes that are common within any particular group of writers (as we talked about earlier, a lot of Queer writers address the body)—but CantoMundo and Lambda complicated those conversations, showed me how each person contributing to that conversation is slightly shifting the focus, kind of like when you hold a gem in the light—even if you just rotate it a couple of degrees, you’re still looking at the same gem, but what you’re looking at has changed: a different spot may glimmer more, or maybe a whole side starts to shine brighter, or maybe it stops refracting altogether.

Finally, CantoMundo and Lambda showed me what community actually means—how it requires us to uplift each other, look out for each other, and, most importantly, to leave the door open and actively invite others into the community. Before I had even applied to CantoMundo, for example, I’d already been in contact with a couple of poets who are fellows and was so grateful when they offered me reading suggestions and writing advice (and gentle nudges to apply). Their willingness to reach out beyond CantoMundo poets made me feel welcomed into their community—I admire them for that and keep that in mind whenever I meet new writers. Also, thanks to social media, we regularly celebrate each other’s accomplishments and good news (and we also commiserate with each other when things aren’t going so well). So many members of the community also write book reviews regularly, which is such a wonderful and thoughtful way to support each other—it’s also encouraging me to become better at writing reviews. While aspects of business exist in the writing world, I think it’s really easy to start seeing it as all business, which encourages writers to treat their relationships like business transactions. Places like CantoMundo and Lambda showed me how to resist that, and the friendships I’ve made because of these workshops are constant reminders of the kind of relationships that fulfill me.

MQ: In regards to the business side of poetry, what have you been most surprised to learn since Phantom Tongue was accepted for publication?

SS: I am incredibly grateful that Phantom Tongue found a home with Sundress Publications—Erin Elizabeth Smith, Sara Henning, and the rest of the Sundress Publications team totally blew me away with all of their feedback, time, help, and patience. One of the more surprising aspects of this process was creating a press kit (this was actually the first time I’d even heard of the term). It ended up being a compilation of a whole bunch of things related to Phantom Tongue that I’d never even thought about assembling together in a single file—varying author bios, blurbs, summaries, interviews, and a few other things. It definitely comes in handy! Something else that’s continuing to surprise me is the marketing dimension of having a book—I actually saw a couple of poets make fliers advertising that they were booking for their tours and I was like Dang. That’s a good idea—I should probably do that too! Also, when I was submitting Phantom Tongue to presses and contests, I thought that that was the end of that. But, then I found out there’s a whole field of prizes for books after they’re published, many of which require you to submit for consideration. (And, again, Sundress saves the day with a wonderful list of places to consider.) So now I’m preparing to send it out to some of those contests and looking into securing readings in California and beyond. (Shameless plug: I’d love to visit your writing community in person or via Skype!) I’m still learning how this whole “marketing” process works.

MQ: Can you share about the cover art for Phantom Tongue?

SS: Yes! The painting’s title is Obstructed by the Chicana artist Guadalupe Ramirez. You can find more of her art on Instagram: guadaluperamirez.art. Guadalupe told me that she gets a lot of her inspiration from poetry and other literature—she actually painted Obstructed in response to Phantom Tongue. She showed me the painting in its early stages—it had a blue background with the side profile view of a man. She ended up covering his face in wax and scattered gold flakes over the wax. She also scratched the background to give it texture—you can see it on the cover, and in real life the dimensions are even more pronounced: the wax and gold rise from the face while the background ends up sinking. She explained that the wax covering his face is a representation of the toxic cultural narratives assigned to a (Queer) man of color—they affect how he sees himself and sees the world. She said that she wanted the gold to embody the aspects of himself that he wants to embrace, the parts of himself that toxic cultural narratives make inaccessible. Ironically, though, it’s the wax (toxic cultural narratives) that allows the gold (his aspirational self) to even stick, showing how toxic cultural narratives are a huge aspect of his identity, and the only way for him to get past those narratives is to actually acknowledge their influence in his life. Her work has actually been commissioned and published by other writers, too, and I’m always amazed by how she balances the political with the humanity of her subjects.

MQ: What are you working on now?

SS: When I wrote Phantom Tongue, I was concerned by the toxicity of internalized racism and homophobia, how that process harms an individual and their personal relationships. Now, I’m working on some newer poems that attempt to interrogate the ways in which I’m complicit in systemic oppression. I’ve been drafting poems where the speaker is the perpetrator of harm, not the recipient. It scares me and makes me uncomfortable, but the fact that I can even walk away from these kinds of poems shows my privilege and reminds me I need to keep trying.

Steven Sanchez is the author of Phantom Tongue (Sundress Publications, 2018), selected by Mark Doty as the winner of Marsh Hawk Press’ Rochelle Ratner Memorial Award. A CantoMundo Fellow and Lambda Literary Fellow, his poems have appeared in publications that include Poet Lore, Nimrod, Muzzle, The Blueshift Journal, andGlass: A Journal of Poetry.

Monique Quintana is a contributing editor at Luna Luna Magazine, and her work has appeared in Huizache, Bordersenses, and The Acentos Review, among other publications. She is an alumna of the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley and the Sundress Academy of the Arts and has been nominated for Best of the Net. She blogs about Latinx literature at her site, Blood Moon and is a pop culture contributor for Clash Media.You can find her at moniquequintana.com