BY CHRISTINA BERKE

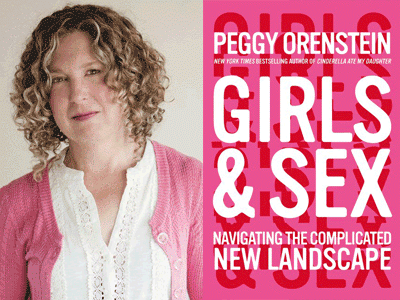

Much has changed between my generation and my mother’s generation in terms of technology, politics, gender norms, but most notably with dating and sex. In her new book, Girls & Sex, journalist and mother Peggy Orenstein interviews over 70 women and discusses sexuality with experts to reveal some shocking (and often overlooked) truths about the reality of girls and sex.

She explores slut shaming, sexual development and education, objectification, body image and anxiety, campus rape, the new hookup culture, and the difference between sexualization and sexuality: how sex for females is “a performance rather than a felt experience.” Orenstein examines modern-day assumptions about women’s bodies, and who they exist for— are they only for men’s pleasure, for them to look at, touch, speak about, at their disposal?

Christina Berke: Your book is bringing to light something that should have been discussed years ago. What do you think the delay has been and why? Do you think there is going to be a new wave of feminists after this book is released?

Peggy Orenstein: Wouldn’t it be great if it sparked a new wave of feminism around these most intimate issues? Of course, one reason we’re here is abstinence-only education, which has been an unmitigated disaster. And an ever-intensifying pop and social media culture that persists in telling young women that how their body looks to others is more important than how it feels to them (did you see Rachel Bloom’s video, “Put Yourself First In a Sexy Way?” It is brilliant on this).

I also think there’s a way that after parents stopped saying “don’t” about sex, that they didn’t replace it with anything. Or if they did, they replaced it with discussions of reproduction and disease and pregnancy, but didn’t talk to girls about sexual entitlement and autonomy; about balancing risk and danger with the joys and pleasures of sex. We are strangely more comfortable, even in liberal circles, with talking about girls’ victimization and peril than with their capacity for pleasure. So when there’s this complete silence, how are girls supposed to learn it? No wonder they start their early sexual experiences believing that pleasure is for boys.

I talk in the book about Sara McClellan’s phrase, “Intimate justice.” Sex is a social justice issue, just like housework and equity in the workplace. You have to ask: Who has the right to engage in a sexual experience? Who has the right to enjoy it? Who is the primary beneficiary of it? What does “good enough” mean to each partner?

CB: How did you stay not only organized during this interview process and writing, but how did you not become depressed, disheartened, and scared for the future of females, for your daughter?

PO: Well, staying organized, that I don’t know. I always look back on a book after I’ve written it and can’t imagine how it got done. It’s like I put it under my pillow and it was written by elves. I think it’s like childbirth—you just forget all the pain! But I never become disheartened. I believe in the power of books to jump start conversations that can make change.

I saw it with "Cinderella Ate My Daughter." That book helped spark real and substantive change in the culture of little girls. Not total transformation, but change. Or you see it with the work of Michael Pollan. Who had heard of free range chicken before he came along?

CB: You said that girls opened up to you right away, even though they were discussing some pretty heavy topics including rape. What do you think made them feel so at ease? How can we create a space like that for girls everywhere?

PO: I think it was because I asked. But honestly, I blew the first couple of interviews because I think my surprise and my judgment showed. I wasn’t truly listening. So I had to learn to talk about sex with girls. Once I did, though, they would tell me repeatedly that no one had ever asked them questions like these and they were so glad I did. Some of them have stayed in touch with me to this day.

They say the conversations had huge impact not only on their personal lives but even on things like their college majors. In terms of finding a way to create that space, I think we can. I think we certainly can on an individual level with daughters, nieces, friends (both adults and teens). It’s a matter of practice.

It’s not easy to talk about sex at first because we learn we’re not supposed to. but once you start, it gets less difficult And I have to say, when I’ve done it, with friends’ kids or nieces, it’s created a kind of bond that is exactly what one hopes to have with girls, a sense of trust and that you’re on their side.

CB: You said in your acknowledgments that when you write, you get anxious, grouchy, obsessive, self-absorbed and emotionally distant. Can you talk more about your writing process/routines/ rituals?

PO: Yeah. All of that is true. It might be true when I’m not writing as well….I’m pretty regular in my routine, though. Because I have a husband and a child, I can’t work whenever I want to or for as long as I feel like it (though I do spend way too much time online).

Typically my husband, who is a documentary filmmaker, gets up with our daughter and gets her ready for school and out the door, so my mornings are free to work or work out. I pick her up at the end of her day, so that’s how we organize our time. Whether I get work done during my time or not is on me.

The distractions of the modern world—email, social media—are very hard for me to manage. I try to use apps like Freedom or SelfControl. I always feel hugely better when I do.

CB: While there won’t be a cure-all prescriptive for how we can educate young people about sex, what do you think is the more effective way to go about it? You discussed some innovative techniques, like the thought simulator on affirmative consent, the teacher’s open discussion and vulva puppet, and parental discussions (multiple, a far cry from “the talk”).

What do you think is the most effective (besides parent conversations, which also begs the question–how do they do this)? What are you planning to do personally for your daughter and her friends?

PO: I don’t think there’s one answer. I think all of those things need to be in play. I talk a lot about the Dutch model, because their girls report so much more agency in their early experiences than our girls. And that’s because schools, teachers, doctors and parents all talk very explicitly about sex with them—all forms of sex—and about balancing joy, pleasure, responsibility, ethics, about relationship-building, decision-making, sober sex, all of the things we ignore. Can that happen here? I don’t know.

In some places, for sure. I end the book in such a classroom. As for me, I don’t like to talk too much about my daughter, because she deserves her privacy, but I do take opportunities to make sexual issues a normal part of conversations, whether it’s pointing out sexualization, pointing out that in movies they use a shorthand for sex (ripping your clothes off, quick intercourse, everyone is instantly orgasmic) that is not realistic, or talking about knowing your own body and its responses. She’s gotten used to it. Sometimes she says, “Mom, stop talking about your book.” That’s fine, too.

CB: How did you get started on this project? How did you go about getting these connections to talk to people, to get them to open up? (I’m thinking in particular about how you got in touch with that teacher, how you discovered the sexual politics of Holland, etc.)

PO: You know, it’s such an organic process, it’s hard to track. I’ve been thinking about writing this book for many, many years. I touched on its themes in my first book, Schoolgirls, in 1994, and again in Flux in 2000 and again in "Cinderella Ate My Daughter" in 2011. So I’ve been writing about girls for a long time. I didn’t know what this book would really be about. I just knew that something about the topic of girls and sex compelled me, and because I’d had successful books and was a relatively well-known writer I could get enough of an advance to mostly get me through without taking on too much other work. Though I'm always doing magazine work and speaking as well.

We live modestly and while I wish sometimes we had more security, what we have rather than stuff is time, freedom, and meaningful work. It’s a trade-off. I found the girls by asking around. I found Charis (the teacher) by asking around. I found Holland by reading widely on my subject. Some of it is happenstance, some of it is trust that my instincts will lead me in the right direction. You have to be able to tolerate a lot of uncertainty and dark nights of the soul to do this kind of work.

CB: I taught middle school in the past, and I had many students open up to me about situations that, frankly, I didn’t know how to answer. Part of it was this fear of losing my job (having a conversation with a minor about sex). Because of my faltering, many didn’t open up to me again. What can adults do when they’re thrown into situations like this but aren’t prepared?

PO: It is very hard and that sounds like a tough situation. It’s ok not to have answers. It’s ok to say you know, I need to think about what you’re telling me and think about the responses and resources that would be most helpful, and can we make another date to talk about this and I”ll be more prepared to answer you.

CB: The entire time I was reading this book, and even from the title, I kept thinking about the natural binary that it creates between males and females. What about boys and sex? Naturally girls are more often assaulted, but do you have any plans to do a project that focuses on boys? Girls can only do so much, and as you said, there is no rape without a rapist…

PO: Yeah, I know. It’s a issue. I do hope that since many parents of girls are also parents of boys that it will have an effect on boys as well. And I wish someone would write the book on boys and sex. I’m not the right person for that. It’s not my calling. It’s really girls who speak to me, metaphorically and in reality.

Peggy Orenstein’s book newest book, "Girls & Sex: Navigating the Complicated New Landscape" (released March 29, Harper) offers a clear-eyed picture of the new sexual landscape girls face in the post-princess stage—high school through college—and reveals how they are negotiating it.. Her previous books include The New York Times best-sellers "Cinderella Ate My Daughter" and "Waiting for Daisy" as well as "Flux: Women on Sex, Work, Kids, Love and Life in a Half-Changed World" and the classic "SchoolGirls: Young Women, Self-Esteem and the Confidence Gap."

A contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine, Peggy has also written for such publications as The Los Angeles Times, Vogue, Elle, More, Mother Jones, Slate, O: The Oprah Magazine, New York Magazine and The New Yorker, and has contributed commentaries to NPR’s “All Things Considered.” Her articles have been anthologized multiple times, including in The Best American Science Writing. She has been a keynote speaker at numerous colleges and conferences and has been featured on, among other programs, Nightline, Good Morning America, The Today Show, NPR’s Fresh Air and Morning Edition and CBC’s As It Happens.

In 2012, The Columbia Journalism Review named Peggy one of its “40 women who changed the media business in the past 40 years.” She has been recognized for her “Outstanding Coverage of Family Diversity,” by the Council on Contemporary Families and received a Books For A Better Life Award for Waiting for Daisy. Her work has also been honored by the Commonwealth Club of California, the National Women’s Political Caucus of California and Planned Parenthood Federation of America. Additionally, she has been awarded fellowships from the United States-Japan Foundation and the Asian Cultural Council.

Born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Peggy is a graduate of Oberlin College and lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her husband, filmmaker Steven Okazaki, and their daughter, Daisy.

Christina Berke is a New York-based writer and editor. Her work can be seen inThought Catalog, Eleven and a Half, Literary Orphans, and elsewhere. She is currently an MFA candidate and is working on her debut novel.