BY JOANNA C. VALENTE

Poetry isn’t a grand mystery. It can be, and there are certainly moments where you want ambiguity, to even misguide the reader at first, but it doesn’t have to be confusing. Your reader is smart and sophisticated, but they also have an attention span. Like you.

Writing poetry, like fiction (and making any kind of art), is about utilizing all aspects of your brain, your body, your craft. I regularly teach poetry workshops (and I used to be a high school English teacher), so I'm constantly thinking of new ways to challenge myself and others—and finding ways to keep pushing myself to explore the nuances of poetry. Being a former high school teacher (think "Ferris Bueller"), I had to be pretty creative to get 15-year-olds to listen to me.

What I’ve learned: We need to stop thinking of poems as poems, but as art pieces that weave together different techniques from other disciplines, in a way to expand the line, the beat, the image.

1. Treat the poem like a film or commercial.

Poems are moments in time that we isolate—which lends itself to having a cinematic, experiential quality. In order to ground this moment in some kind of time or context, writing the moment like a scene, using specific details (like dialogue!), helps the reader to vividly see the experience in their mind, even if it’s just a tone or mood or atmosphere.

Good films to watch as examples of creating tone, mood, tension, and scene:

Vertigo

2046

Amelie

Brief Encounter

The Man Who Laughs

2. Your poem has a canvas, like a painting.

The way the poem looks on the page—the line breaks, the stanzas, the use of the negative space on the page—draws the eye, in the same way a painting does. Use the full page. Only use the bottom left of the page. Take risks, question everything you do. Creating pauses and silences, or doing the opposite and creating chaos, will change the reader’s experience without changing the actual content.

RELATED: Poet Robert Balun on His Obsessions, Process, & 'Self (Ceremony)'

Paintings to get inspired by:

Bosch - "The Garden of Earthly Delights"

By Hieronymus Bosch - The Prado in Google Earth: Home - scaled down from 8 level of zoom, JPEG compression quality: Photoshop 10., Public Domain, Link

Egon Schiele- "Self Portrait"

By Egon Schiele - The Yorck Project: 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei. DVD-ROM, 2002. ISBN 3936122202. Distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH., Public Domain, Link

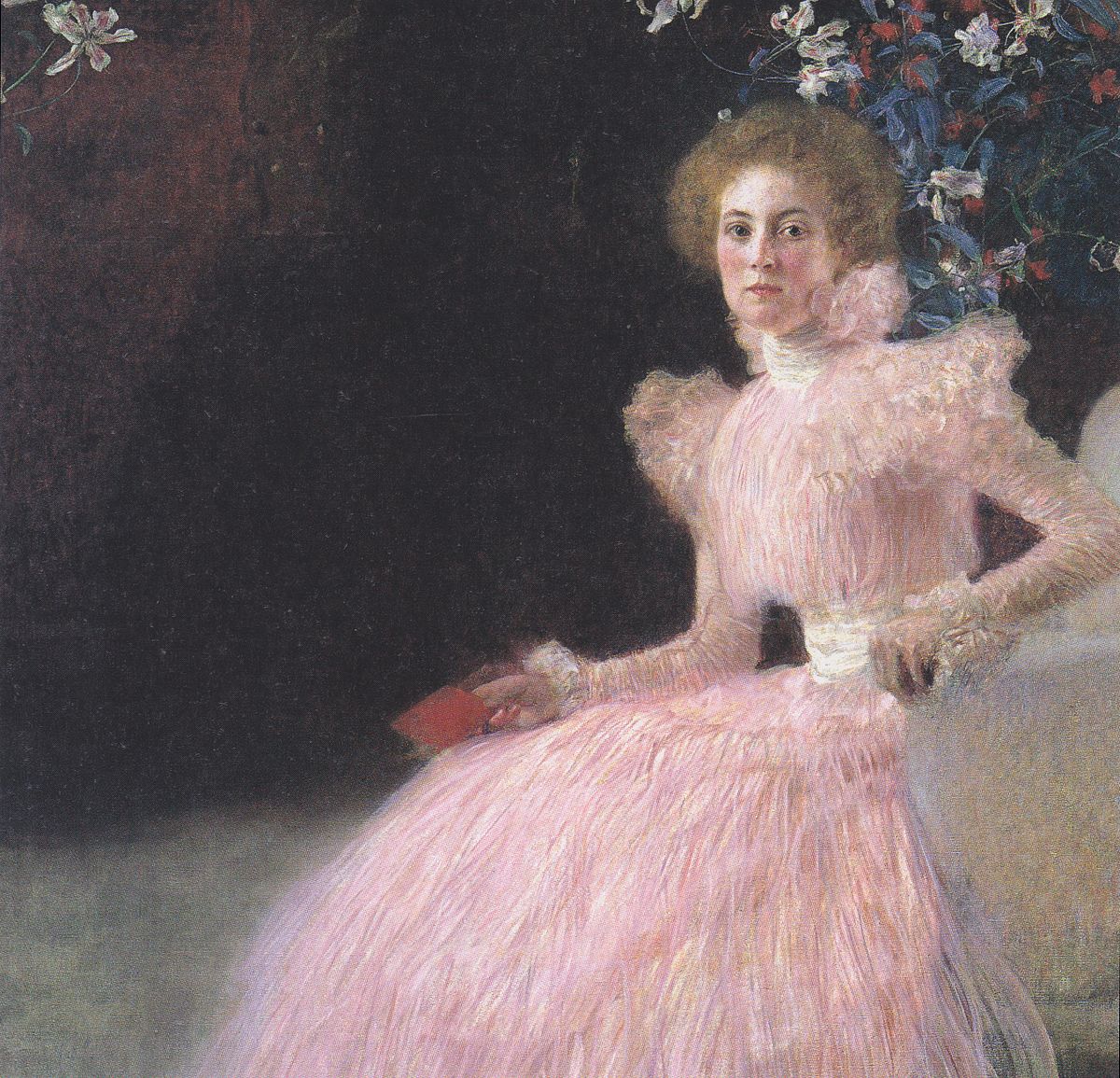

Gustav Klimt - "Sonja Knips"

By Gustav Klimt - repro from artbook, Public Domain, Link

Faith Ringgold - "Self Portrait"

Picasso - "Girl with Mandolin"

3. Jazz is everything in poetry.

I highly encourage all writers of poetry to listen to jazz and use the rhythm as a way to break lines, create movement within the lines themselves, and learn how to use unpredictability, contradiction, repetition, and spontaneity. When we break lines and stanzas, besides creating double meanings and progressing a narrative arc, we are also creating the rhythmic map for our readers to follow. We can break our own rules, and should, so as not to give them all the keys to every door—or essentially, see the tricks before the poem ends. Because then your poem is predictable, and your reader is bored.

RELATED: The Voices We Don’t Hear in Poetry Are the Ones We Need To

Songs to listen to:

Miles Davis - "Blue in Green"

Dizzy Gillespie - "All the Things You Are"

Chick Corea - "Now He Sings, Now He Sobs"

Bobby Hutcherson - "Love Song"

Andrew Hill - "Dedication"

4. Poetry is like fiction.

You still need to tell a story, even if it’s abstract and nonlinear. All poems have stories, even if it's about a shoe. What's the shoe's story? What’s the climax, the rising action, the resolution? If your reader doesn’t know what’s going on, they’re likely to be frustrated, and probably stop reading—because their mind will shut down and move onto something else. Having narrative in poetry also doesn’t mean your poem reads like exactly like a story even, but instead means the reader can relate to whatever emotion or loose narrative thread there may be.

Stories you should read to get ideas of pacing and silences:

Joyce Carol Oates - "Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?"

Sarah Gerard - "Excerpt of Binary Star"

Sean H. Doyle – "Hallucinatorium"

Han Yujoo – "The Impossible Fairytale, excerpt"

Jamaica Kincaid - "Biography of a Dress"

5. Learning blank verse will save your life.

And not even for the whole "you have to learn the rules to break the rules" trope, but because blank verse will teach you how to listen to your body, how to listen to music, and how to actually hear words and syllables. If you become somewhat accustomed to counting syllables, to understanding the difference between a trochaic beat versus an iambic one, you’ll be able to create a soundscape that may feel purposefully strange, or slow, or smooth, or dreamlike—and in conjunction with other techniques, it creates so many layers to your work. Kind of like a really good cake.

Poems in blank verse:

Jason Koo - "Believeland"

Candace Williams - "Black Sonnet"

John Milton - "Excerpt of Paradise Lost"

Joshua Mehigan - "The Fair"

Reginald Dwayne Betts - "A Postmodern Two-Step"

6. Don’t underestimate suspension, tension and unpredictability, aside from the narrative.

How can you break lines purposefully to do this? How can you create space and silence within the lines? Having the reader anxious for the next image, line, and sound will heighten the sense of urgency—and that’s something you want in a poem, as in any art. If you’re watching a TV show, and you feel bored, you will probably stop engaging in it as much. Using the space between words, employing indentation, writing in persona, reversing the usual diction, are some ways to do this.

Poems with suspense:

Kim Hyesoon - "The Way Mommy Bear Eats a Swarm of Fire Ants"

Srikanth Reddy - "Monsoon Ecologue"

Patricia Spears Jones - "Encounter and Farewell"

Patricia Smith - "Skinhead"

Jericho Brown – "Bullet Points"

7. Most of all, be vulnerable, but also be a journalist.

Poems aren’t written in voids. They aren’t written without emotion or vulnerability—and while not everything in a poem has to be true (it’s OK to change the color of your grandmother’s shoes, the exact details of your relationship, etc.), the emotion can’t be forced. Because your reader will know. Maybe they won’t catch on the first time, but eventually, they’ll see the lack of authentic vulnerability.

Vulnerability makes us relatable, but it also makes us highlight experiences that others may also be struggling through. We need to give visibility to experiences that are hard to write about, even talk about. For instance, when a poet writes about their chronic illness, or their sexual assault, or abortion, or their experiences with race, it helps connect others together as a community—it helps us all feel less alone. And that’s real. And that realness can’t be traded for something else.

Of course, using an objective lens can be helpful, which can be done through writing in a persona. For instance, I myself have written poems about my sexual assault, but written through various voices and personas has enabled me to isolate the moment within another lens, making it easier to deal with the details.

Poems with vulnerability:

Natalie Eilbert - "Let Everything Happen to You"

Faylita Hicks - "About My Daughter Who I Gave A Way"

Maggie Smith - "Good Bones"

Joshua Jennifer Espinoza - "Wake Me Up When My Gender Ends"

Cortney Lamar Charleston - "I'm Not Racist"

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York, and is the author of Sirs & Madams (Aldrich Press, 2014), The Gods Are Dead (Deadly Chaps Press, 2015), Marys of the Sea (The Operating System, 2017), Xenos (Agape Editions, 2016) and the editor of A Shadow Map: An Anthology by Survivors of Sexual Assault (CCM, 2017). Joanna received a MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College, and is also the founder of Yes, Poetry, a managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine and CCM, as well as an instructor at Brooklyn Poets. Some of their writing has appeared, or is forthcoming, in Brooklyn Magazine, Prelude, Apogee, Spork, The Feminist Wire, BUST, and elsewhere.