BY FOX HENRY FRAZIER

When I was eight years old, I first visited the violent place where I would make my adult home: where I would first read Joan Didion, where I would experience wildfires and earthquakes firsthand, where I would come to understand the Manson murders as a point of cultural fixation. Where I would marry my high school sweetheart (in Rancho Palos Verdes, where Joan Didion once lived). Where I would try to look evil squarely in the face and figure out what to do next.

I travelled to the Los Angeles area many times as a child. We had family in Orange County, and winter visits to their homes provided relief from the ice and isolation of upstate New York. From a young age, I have been mesmerized by the wildfires and earthquakes that television news stations brought into my family’s living room. That people I loved, and to whom I was related, were in proximity to these cataclysmic events of the natural world made the events real to me in a way that they otherwise likely would not have been.

The year I was eight, the city burned for several days as riots spread in reaction to the verdict that allowed police to walk free after the videotaped beating of Rodney King. The National Guard was stationed around the University of Southern California; 17 years after the riots, and 18 years after the beating itself, I would begin my performance there as a doctoral candidate.

When I finally moved to Los Angeles from New York in my early twenties, I stayed with a family in Laguna Hills named the Palmers. My then-partner, Iago, and I had been invited to stay with them for six months; we stayed for about six weeks. One day early in our stay, I noticed a house in the Palmers’ expansive neighborhood with a lot of birds on the roof and in the yard. There was netting around the house that I thought was intended to keep the birds in. I wondered if they were exotic pets, or if the homeowners might be avian breeders or dealers. Molly explained to me that, rather, the nets were intended to help keep the birds out. She told me that about twenty years earlier, her eldest daughter had befriended the newly adopted daughter of the couple who owned the Bird House. The girl was an orphan from a European country that Molly did not name. Molly said that she had thought the young girl a little odd; she had a preoccupation with cats. More than that, really, Molly elaborated, the girl seemed to have a minor obsession with trying to seem catlike—a tendency presented in the manner of an idée fixe. Molly had thought that it might be a byproduct of the young girl’s rough life before being adopted into an affluent Southern Californian family. The little girl had likely not had much in the way of socialization or even formal education. Perhaps she had had a feline friend at the orphanage. Or had wished for one.

One night, Molly told me, she and Ken went out and left their daughter in the care of a babysitter; they had allowed their daughter to invite her new friend to their house for a sleepover. They had only been gone for a short time when the babysitter called them, frantic. The little girl obsessed with cats had wedged herself under Molly and Ken’s bed. Underneath her jacket she was covered in blood that did not appear to be her own. The little cat girl had killed her adoptive parents’ cats before coming to attend the sleepover. She said that she had drunk their blood before deciding to wear some of it, “for strength.” She claimed that her adoptive family wanted to kill her, and this was a mode of self-protection—a means of gathering strength. After she was sent away to a psychiatric facility, birds began to flock to the house, congregating everywhere.

I found the story difficult to believe. Despite my skepticism, I avoided passing the Bird House, taking extra turns and driving down extra streets. I did not want to be near the place. I could not say exactly why I didn’t want to be near it, but my propensity for avoidance seemed a harmless self-indulgence—a quirk. After we moved out of the neighborhood, however, I continued to think about the little girl, about the house, and about the shadow of birds that seemed to constantly hover over it. I had never regarded the appearance of animals as ominous before moving to Southern California.

***

When I was eleven, I wrote a short story about attempting to confront evil directly, and I happened to name the protagonist, a stand-in for myself, Winnifred Chapman. Both names had (unrelated) personal significance to me.

When I was twenty-nine, I began an essay about the Manson murders. It was then that I learned the identity of the real Winnifred Chapman. I admitted Iago’s cruelty to myself, and left. I began dating my high school sweetheart, Cas—whose real name is Casimir, a nod to the French part of his ancestry. Casimir vaguely hates France, although he has never been to France and cannot articulate the reason for his disdain. Nevertheless, he insists—and has insisted, since we were both fourteen years old—on being called Cas. Cas and I had shared an affinity for The Downward Spiral upon its initial release. For Cas, I moved back to upstate New York, a place that had been the setting for grisly murders of several young women when I was growing up. And, during the year that I was twenty-nine, Cas would introduce me to two different men who would both soon, in unrelated circumstances, murder their wives.

If you add eight, eleven, and twenty-nine together, their sum equals forty-eight. And it had, as I finished the first draft of this piece in August of 2017, been forty-eight years since the Manson murders took place.

Of course, as soon as I noticed this, I was certain that it meant nothing. And yet since I have noticed this pattern of numeric connection, it retains my focus even after I have placed my focus elsewhere. It nags at me. I am not sure why, or what I am supposed to do with it.

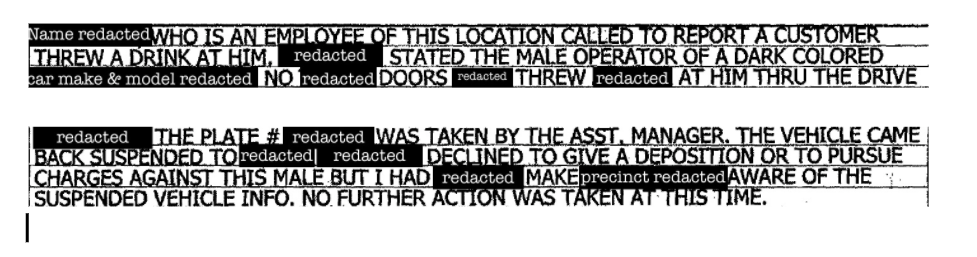

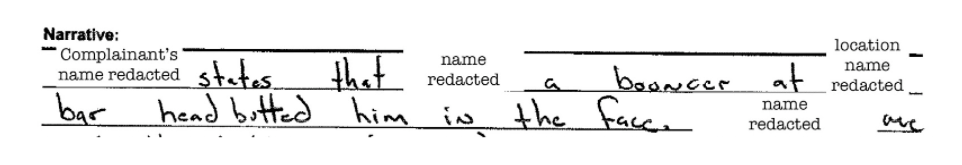

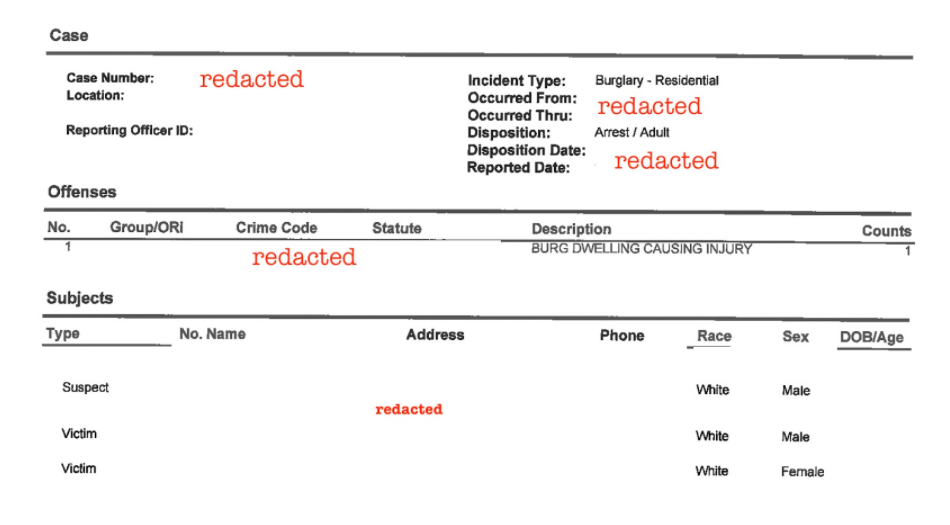

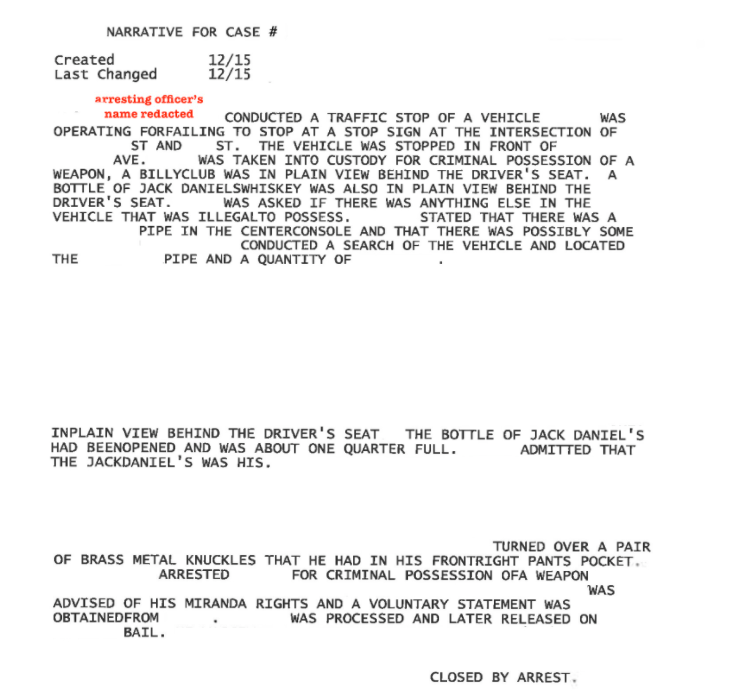

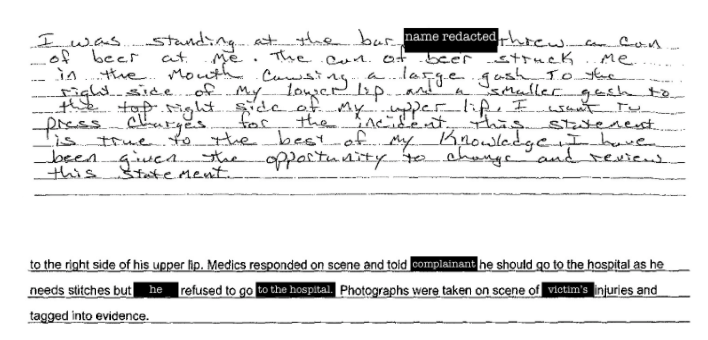

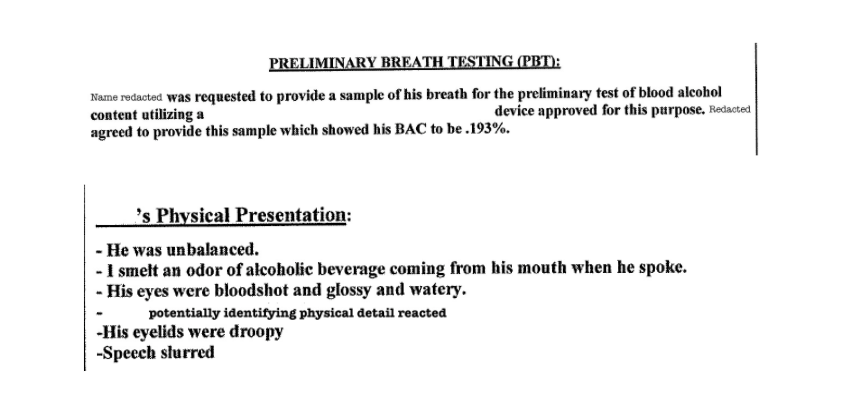

I struggled, during the year that I was twenty-nine, and for many years after, with admitting Cas’s cruel streak. Sometimes I ignored it because I thought he would protect me from a world that is often cruel, dangerous, and hostile specifically towards women. Sometimes, when he turned his cruel streak on me, I rationalized that it wasn’t really coming from him, that this tendency in him had evolved as a survival mechanism due to the circumstances in which he grew up. I pushed it out of my mind, even when he was arrested for assault six months after we started dating. Even a few months after that, when I saw him assault a fast-food employee and evade arrest because the employee declined to press charges.

***

During my brief and turbulent stay at the Palmer residence, Molly requested my help with moving a kitchsy-looking statue from its perch at one end of their outdoor pool to the other, near the lagoon-style hot tub. Molly asked for my help because, she said, she could tell I was a witch. She, who had been raised traditional Southern Christian, asked me to raise up some energies so that we could move this statue, which must have weighed at least a couple hundred pounds. She said she had seen some nuns do this raising of energies once—nothing Satanic or occult about it—and one of the nuns, well, she was a nun but she was also a witch. Mildly flattered by this odd idea regarding my magical capacities to displace formidable physical obstacles, I channeled my early adolescent experiences of “light as a feather, stiff as a board,” and did my best to raise some energy. I felt foolish and a bit embarrassed. The statue wouldn’t budge. The next morning, when we awoke, the statue had indeed been moved to the far end of the poolside. I asked Molly about it, awkwardly apologizing for my inability to help the way she had asked. She looked at me, puzzled. “But you did move it, Fox,” she said. “I watched you move it.” I was confused and embarrassed and uncomfortable. I said nothing else.

Molly chatted to us at dinner that night about crystals and crystal healings. Iago and I shared a conspiratorial glance. What kind of West Coast nonsense was this? A black widow spider repeatedly climbed the arch of Iago’s foot under the table during the course of the meal. It did not bite him, but neither could he apprehend it. Every time I sighted it and he pulled back, it ran inside a crevice under the table. Molly told us not to worry. She said the world is full of these things, that they cannot be avoided. She herself had once been bitten.

The fires began in earnest that week. Iago had already hit me once, and had coerced sex from me multiple times. He had not yet begun ending minor arguments about housework by standing over me with a raised fist. You know, Molly once said to me in an exasperated tone, you don’t have to answer to him. I had not yet come to the point of acknowledging Iago’s cruelty and leaving him. But, in retrospect, I don’t know why I wasn’t more afraid of him by that time, or of what might have come next. It seemed, in my mind, somehow linked to the way I felt about the fires. They were objectively terrifying, but I had trouble feeling my fear; because of that, I had trouble understanding that I was afraid. I could not bring myself to believe that something like that might be the end of me.

***

Joan Didion is not the only writer to have made the connection that she so famously made between the Santa Ana winds and disturbances in human behavior, similar to those associated with the full moon. Raymond Chandler once described Los Angeles during a Santa Ana: “On nights like that, every booze party ends in a knife fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands’ necks. Anything can happen.” Didion relates, in a tone less dramatic, supportive reportage:

“…doctors hear about headaches and nausea and allergies, about ‘nervousness,’ about ‘depression.’ In Los Angeles, some teachers

do not attempt to conduct formal classes during a Santa Ana,

because the children become unmanageable.”

Though her extended description of the Santa Ana and its effects sounds almost like magical realism, Didion’s reportage is accurate. Positive ions and negative ions tend to have opposing effects on us. Studies have indicated that negative ions possess anti-microbial properties, and exert mood-stabilizing effects on human beings by augmenting serotonin levels. Negative ions, naturally generated when water molecules collide, explain why many people find showers refreshing, and oceanside stays rejuvenating. Positive ions, naturally generated by föhn winds like the Santa Ana, tend to cause humans tension, aggression, and general malaise.

It troubles me that so many of us reflexively mistrust the connections between the earth and our bodies—that we often need these things “proven” before we accept their reality. Our bodies, after all, are recycled celestial matter; we are literally, as Joni Mitchell sang, stardust. Because we know that we are of this planet, it’s hard to understand our relationship with it sometimes—the way we terrorize and damage it, the way we have so little faith in our deep and ancient connection to it. The way we are surprised when our Earth sometimes violently cleanses herself of our abusive presence—through virus, through wind and fire, through the violent tendencies coded into human DNA that often motivate us to obliterate one another in pursuit of resources.

“Los Angeles weather,” Didion writes, “is the weather of catastrophe, of apocalypse, and, just as the reliably long and bitter winters of New England determine the way life is lived there, so the violence and the unpredictability of the Santa Ana affect the entire quality of life in Los Angeles, accentuate its impermanence, its unreliability. The wind shows us how close to the edge we are.”

Didion was correct, I think, that people who have not lived in Los Angeles have a difficult time understanding how radically the Santa Ana and its apocalyptic conjurings figure into local culture. Los Angeles has many ways of observing and remembering past traumas. We internalize via earthquake drills and the quietly anxious hypervigilance of fire season, but also through guided tours about celebrity murders, serial killers, violent historical events, grisly and tragic deaths of young and vulnerable people. They are, of course, colloquially known as “tourist traps.” You take the shiny bait, and get snapped up into—something. The unspeakable is spoken by a hype-man, over a loudspeaker, for your entertainment. The unthinkable becomes an attraction—becomes attractive. We have shrines to this violence, which we term museums. Amusement mausoleums. One such enterprise is the Museum of Death in Hollywood.

***

I thought that Cas, who proposed to me in Las Vegas and then twice in Los Angeles, was the love of my life. I grew up with the saying that once is an accident, twice is a coincidence, and three times is the truth. Cas asked me three times, I said yes three times, and then we got married three times. But I understood even then that Cas was a conduit for my connection to a very dark place—the hometown we share with Rod Serling, in upstate New York, that I believe to be a spiritual vortex. When I moved back for a year to be with Cas, he introduced me to two different men who would both soon become murderers. Despite the intense and enduring love I felt for Cas—which a doctor would later explain to me as a traumatic bond, and not real love at all—I have only contempt and revulsion for the types of violence he has chosen to embrace, and the dark ways in which those violences have shaped him.

And yet, I also understand the place from which Cas comes in more academic terms. It is brutal—the sort of which cosmopolitan and affluent suburban Americans would prefer to pretend does not exist. Cas’s hard-drinking, thrill-seeking, drug-addled, blue-collar subculture of a dying industrial town is nestled among the intersections of various dearths of opportunity. Because the degrees of difference separating punishment from reward exist on such a minute scale, in this place, there are really only a few types of social currency that one can hope to possess. One of those few significant currencies is a sense of dominance, almost always expressed in terms of physicality. Which almost always means violence or the threat of violence.

In the culture of the place I am describing, the physical dominance expressed by a man in public settings will be granted socially, by extension, to his female partner (if he has one) for as long as they are romantically linked. It is a sort of power garnered by association. One of the effects of this complicated social contract is that male aggression tends to be appreciated and actively encouraged by female romantic partners, even if they understand that same aggression as personally destructive to them. The credibility of one’s physical dominance and power are absolutely central to the quality of life one may carve out for oneself. As far as I have been able to gather through immersion and observation, in order to maintain this type of credibility in such an environment, you must assume that everyone around you is willing to physically hurt you—and that they may even want to. For a man like Cas, who is used to overpowering any opponent in a physical altercation, this expectation is not the same thing as fear: it is worn like a badge, with a certain amount of swagger. He would like you to make him prove how tough he is.

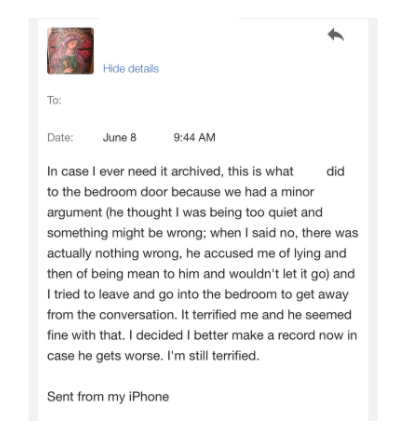

I tried to talk to Cas about this once; his reaction was to lash out. I interpreted his aggression as hurt feelings, and never brought up the topic again. But, as Audre Lorde observed so many decades ago, “My silences had not protected me. Your silence will not protect you.” This proved literally true: one morning, a little over a year into our marriage, Cas asked me why I was being so quiet. Surprised, I reassured him several times that nothing was wrong, that I was simply drinking coffee and hanging out with him in our living room on an early weekend morning, and didn’t have much to say. Cas, who had already consumed several shots of bourbon, began to scream at me that I was weaponizing my silence in order to punish him for some imagined offense. After several attempts to reiterate that nothing was wrong, and that I was not upset with him, I got up and went into the bedroom. I heard Cas get up to follow me into the bedroom. I was scared; I locked the door. Cas punched through the door. Terrified, I tried to leave. Cas blocked the path to our apartment door with his body and asked me in a very quiet voice not to go. He said that the door shouldn’t have caved under his fist like that, that it was poorly made. That I shouldn’t have locked the door, because he had the right to go into any room of his house that he wanted. Terrified, I agreed to stay.

***

Cas drove us to the Death Museum in my Volkswagen Beetle, the car that I bought after I left Iago. Cas and I were hit twice on the freeway that year, both times in my little white car. Both times, the other drivers were at fault.

When we first came to Los Angeles together, Cas drove a Wrangler: doorless, topless. We drove this way on the freeways. After two weeks, I said to him calmly, matter-of-factly, You know, if someone were to hit us on the freeway with the car in this state, I would probably die. I don’t mean that I would be injured or paralyzed: I mean that I would probably actually die. He looked at me, surprised; then he went outside and put the doors and top on the car, and didn’t say another word about it. I wondered then, and again as we drove to the Museum of Death, what it must be like to move through the world without a persistent, tenacious consciousness of all the things present, at any given moment, that can kill you.

***

Cas and I secretly eloped in Vegas before our real wedding with friends and family. We went to Vegas a lot, in those days. We usually didn’t plan in advance. One of us would say to the other in Friday traffic, “Wanna hit up Vegas instead of going home?” and the other would respond, usually, along the lines of, “Challenge accepted.” It was a short drive through the desert, which I believed to have purifying properties. It was a nice portal into and out of Sin City, which we liked less for the sin and more for the larger-than-life ridiculousness. We used to joke that the only real difference between Las Vegas and Los Angeles is that people who live in Las Vegas are in on the joke. There’s some truth to that, but I no longer think it is the only real difference.

Forty-eight years after the Manson murders, Cas and I settled into married life in a haunted town in the Shadow Hills of Los Angeles County. And forty-eight years after the Manson murders, a lone gunman stayed in a Vegas hotel quite familiar to us, near where we got married, and opened fire on thousands of people attending a concert.

***

Something that particularly struck me during our deeply unpleasant time at the Museum of Death in Hollywood was its confirmation of the Cielo Drive murders as some sort of cultural touchstone for many Americans. Why do we love to fixate on the fact that this one person who killed people—who masterminded the killing of people—liked the song “Helter Skelter”? What is behind our cultural focus on those several people who were killed by him, and by his Family, at this particular address? More to the point, it is not as though America has not perpetrated far grislier, and wider-scale, crimes against humanity than this incident. Why does it stand out in the way that it does? It is true that those murders were horrific. But all murders are horrific, and many around the globe are probably equally or more so—though the competitive comparison of horrific murders feels like a fool’s errand.

I think that part of our macabre fascination with this particular crime, as embodied by its unholy shrine at the Death Museum in Hollywood, is that the people murdered at 10050 Cielo Drive were not only racially and socioeconomically very privileged, but some of them were famous. In popular American imagination, this would have been expected to somehow protect them from such acts of violence. To prevent them from experiencing ultimate helplessness. This crime keeps its place in our collective consciousness in part because people are fearful of the knowledge that these are false promises. If socioeconomic acumen and cultural power won’t keep people safe from one another, then is it possible that nothing could?

I think that many people also enjoy knowing that these things are false promises, that even the wealthy and privileged—often people who exert oppressive influence in the lives of others—are not always as secure as they might seem. Tate’s husband, Polanski, visibly ranked among them: in recent years women have come forward with narratives of assault perpetrated against them in their teenage years by Polanski. If predators are not entirely insulated from the viciousness of the outside world, then perhaps those of them who seem to evade justice might not do so forever.

The convergence of vague attraction, disgust, and discomfort that America seems to feel about the Cielo Drive murders is similar, and I think related, to our grotesque historical relationship with “conventionally pretty” female victimhood: there is an element of hating it, and an element of loving to hate it. And there is an element of simply loving it. How many Americans would celebrate Sharon Tate on the same level if she had instead taken out a gun and blown holes through the bodies of those who sought to harm her? Isn’t part of her legacy and her mystique that the gentle, blonde Madonna figure simply pleaded, helplessly and selflessly—and fruitlessly—for the life of her unborn baby?

And, Manson was a cult leader. America loves a cult leader.

***

My parents had a friend, back in the 1960s, whose name was Charlie Manson. I didn’t know about this until I was twenty-nine years old, living alone in Los Angeles and considering the infamy of the Manson murders that took place at 10050 Cielo Drive. Charlie Manson left Charles Manson’s “Family” right before they began killing people. He wouldn’t say why, although he did confide in my parents, and in his twin, that Charles Manson was “one scary cat.” I know that they spent time in the desert together, using either mescaline or peyote to experience “visions.” I don’t know what the visions were of, and I don’t know what the catalyst was for Charlie Manson deciding to leave the Family.

But it’s not difficult to imagine that—for one utterly hypothetical example—in the 1960s, Jack Nicholson, Roman Polanski, and Warren Beatty might have trolled the Sunset Strip, looking for naive young women to pick up and sexually abuse. Drugs were highly accessible, and wealthy, famous, white men rarely, if ever, got into trouble regarding assault. It’s not difficult to imagine they might at some point have picked up a girl who was either already associated with the Manson Family, or who might have later decided to join. Right? It’s possible to picture Charles Manson, already an unstable person, becoming enraged, then obsessed with the idea of retaliation for an assault against one of “his” women. I am able to envision Charlie Manson finding the apparition of this incensed shadow-self to be unnerving, and getting out while the getting’s still good. Perhaps Charles blamed Polanski and his dissolute associates for Charlie’s desertion of the Family, as well. Perhaps Manson remained fixated on punishing Polanksi until the murders were been executed. His rage might have prevented him from sympathy for Polanksi and Tate’s unborn son, his sense of justice so perverted that he was gratified to hear of Tate crying out for her mother as the knife tore her body. He might have told his Family, This is divine justice. We have done to Polanski what Polanski did to us. To our family.

***

Next we hear of Polanski, he's posing for LIFE next to his front door, where PIG is still visibly written in his late wife's blood.

Next we hear of him after that—everyone knows this story: the helpless thirteen-year-old girl at Jack Nicholson's house, who cries and protests despite the quaaludes and other drugs as Polanksi assaults her multiple times—tortures her. For a long time, people will react to this narrative as though the only thing wrong with it was that the girl was underage. As though there is an appropriate age for a woman to suffer acts of torture. We know that Angelica Huston, also present in the house at the time, hears the girl’s screams and pleas, but does nothing to interfere with the assault or help the victim of Polanski’s acts of torture. We are never told if Angelica Huston feels, or felt, helpless. Whoopi Goldberg tells us on an episode The View, “But it wasn’t rape-rape.” We are never told if she feels helpless, either.

Decades later, Roman Polanski makes a poignant film titled The Pianist, and it wins awards at important ceremonies and festivals he cannot attend for fear of arrest. Adrian Brody wins an Academy Award for his performance in the film. Halle Berry reads Adrian Brody’s name out of the envelope. Brody runs up on stage, grabs her, forcibly bends her over backwards, and shoves his tongue into her mouth in front of everyone. In the moments after the assault, still onstage, Halle Berry uses her fingers to clean his saliva from her face. “I bet they didn’t tell you that was in the gift bag,” Brody says at the microphone, and the audience laughs.

The next day, entertainment news reporters describe the kiss as a fun/ny stunt, and one notes that Halle Berry “good-naturedly played along.” In all the coverage of the nonconsensual kiss, I did not see anyone use the word “assault.” I was a teenager when this happened.

I expressed doubt, privately, to a friend of mine who was slightly older: Was I crazy? Was I overreacting? My friend seemed offended by my self-doubt. “He fucking mauled her,” she responded, indignant, as though I should know better than to feel confused. I felt both shamed and reassured by her reaction—and still confused. If the answer was so clear, why I couldn’t I seem to find it anywhere other than inside myself? For how long has our culture applauded while women are assaulted by men, often in front of other people, often while the assault is photographed or filmed—that is to say, while the assault is treated by witnesses as entertainment? And how long has our culture condoned or excused, in particular, the assault of Black women by white men? And if someone assaults you in front of a crowd, and not a single person appears to find it upsetting—if everyone treats it as entertainment—well, then what? That’s always been the implication, hasn’t it—What are you doing to do about it?

***

Molly had told Iago and me about being bitten by a black widow spider as a small child: I was healthy enough that I got sick right away, she said, which I didn’t understand at the time. You could say that, in this particular instance, I was healthy enough to get sick right away.

We were not, as a culture, healthy enough for this poison to make us sick right away.

***

Trent Reznor recorded The Downward Spiral in the living room of 10050 Cielo Drive. Cas and I listened to that album together in high school; it was one of the few areas in which our musical tastes overlapped. Reznor set up the necessary equipment, some furniture, and named the house Le Pig Studios.

On one hand, I find this behavior sensationalist, exploitative, and disgusting. On the other hand, I think I understand some of the impulse behind it. To place oneself in an erstwhile torture chamber is to expose oneself to the energy of those who suffered there—and of those who caused the suffering. There is an element of vulnerability to this sort of immersion; and to place oneself in danger is to force adaptation. To hurt oneself is to evoke feeling. And, as E. E. Cummings tells us, feeling is first. As in, I hurt myself today/ to see if I still feel.

If we force ourselves to be vulnerable in this way—to respond to horror without the luxury of artifice or boundaries—perhaps we might defeat helplessness by first embracing it. Out of this, the artist creates some sort of transformative response. Spiritually minded people create the transformative energies released through prayer or other ritual.

But even the purest version of this impulse often has ugly results. For example, among many academics and creative people, there exists an obscene and unquestioned myth that if we make art or construct dialogue—participate in the discourse—in response to evil in the world, we are somehow less helpless than those who do not react in these “creative” ways. Art, like prayer, is apparatus; it can be perverted into a self-indulgent illusion. Art and prayer have both been used frequently as excuses to avoid doing any more pedestrian types of work to better the world. To avoid walking through any areas of real risk or danger. To avoid consequences that might disabuse participants of the notion that they and they alone are writing this narrative.

And forty-eight years after the Manson murders, Harvey Weinstein was held publicly accountable for his abuse of young women. It had gone on for decades, and was public knowledge. But the Oscars crowd seemed, suddenly, less willing to pretend that assault is a funny stunt. Accusations against many powerful men in the entertainment industry followed. But even some men who called out this type of abuse were themselves abusers. Ben Affleck posted a statement berating Weinstein, only to have strangers share footage of him humiliating a young actress on live television by groping her breast. Ben Affleck tweeted, “I behaved inappropriately . . . and I sincerely apologize.” Ben Affleck has the reputation of protecting his younger brother’s career in Hollywood since the time that said younger brother was sued for sexually harassing and abusing multiple female co-workers.

During this strange time, I dreamed a lot. I had not yet received any medical evidence that the baby I was carrying would be a girl. But I had multiple dreams in which she was both a girl and a king—a force mighty and celestial. During that strange time, I would not have wanted that energy—those emotions, that stress, those chemicals—inflicted on any baby I might be carrying; however, to expose a girl to that while she was still being formed inside my body, her first protector—I couldn’t. I couldn’t. The hyperemesis gravidarum that I suffered during my pregnancy helped me, in a way: I would otherwise have felt specifically sick at the idea of pushing her outside of my body into a world made and terrorized by men.

Joan Didion appears to have feared that she was some sort of possessed conduit for evil. Some sort of vessel for the occult, someone whose body perpetrated some sort of violent connection to Tate, through Polanski and her nebulous proximity to him. She says, writing has not helped me to see what it means. I think this means, perhaps, that Didion both sees and fears what it could mean, and that fear stops her from articulating it, quite. Writing of a similar reaction for Vanity Fair, years later, Lili Anolik suggests that Joan Didion would not allow herself to mention the possibility of the occult in this context:

Didion and the Manson murders were linked, if only in Didion’s mind. She sees occult significance in the fact that Polanski, at a party he attended with Tate, had spilled red wine on the dress she wore to her wedding, and that she and he were godparents to the same child, even if she can’t figure out exactly what that significance is, even if her cool intelligence won’t allow her to use the word “occult.” Yet there’s no question of the guilt in her tone. Is that because she felt somehow responsible for him? Did she believe he was a hallucination she’d conjured mid-migraine (her “vascular headache[s] of blinding severity”)? A vision sprung to life during her psychic collapse the summer before (from the doctor’s report: “In [the patient’s] view she lives in a world of people moved by strange, conflicted, poorly comprehended, and, above all, devious motivations”)? Her bad juju (“I remember a babysitter telling me that she saw death in my aura”) made flesh?

Forty-eight years after the Manson murders, Charles Manson died. He died twelve days after the airing of the AHS: Cult episode that reenacted the 10050 Cielo Drive murders, a week after his birthday, and four days after I found out via prenatal test results that my dreams and intuitions had been accurate, that my baby is a girl. She was due in May of 2018; nine years earlier, Barkers Ranch had burned to the ground. The earth had begun trying to purify that part of itself—the part where Manson and his Family had dwelled. I moved to Los Angeles three months after the Barkers Ranch fire. On the morning of Manson’s death, the New York Post ran the story, with the headline, “Charles Manson Is Rotting in Hell.” Another paper, more local to me, ran the headline, “Charles Manson Dies in Bakersfield Hospital.” I sometimes stop in Bakersfield on my way to Vegas. Cas and I stopped there on our way to get married.

***

Two weeks later, on my mother’s birthday, Cas and I awoke at 3 a.m. to 50 mph winds shaking our windows. We read that Ventura was burning in the Thomas fire; as we left the house to get coffee before work, we could see that Angeles National Forest, just over the hill from us, was burning. It was not yet dawn, but despite the darkened sky, we could see bright red smoke rising over the mountainside. I realized, from Google Maps being shared by local news sources, that we were in the mandatory evacuation zone for what would eventually be named the Creek Fire.

We left moments before the LAPD roped off our street to begin evacuating people. Due to the severity of my hyperemesis (I had at that point lost more than 10% of my body weight), we went to a hotel rather than the shelter. That night, the Rye Fire broke out. By the following evening, the Skirball Fire was devouring Bel-Air, near the Getty Museum. Celebrities, many of whom live in the area or are friendly with people who live in the area, were reacting on social media as though they had never heard of any of the other fires attacking the Los Angeles area. They were, however, genuine in their devastated reactions to the Skirball Fire. This is, I think, the way humans behave when we have spent a long time thinking, with increasing certainty, that wherever the fires are in the world, they are not in our house, and will not come to our house. Then, suddenly, our homes are on fire, and we are devastated.

The Creek Fire also burned thirty horses alive. I thought about those horses for weeks. What their final moments must have been like. I was silently obsessed with these memories, though they were not my own. You could say I was haunted. The Shadow Hills are haunted, and I live in the Shadow Hills.

***

On that first night of our evacuation, I dreamed that Cas and I were seeking refuge in a hotel from a Los Angeles wildfire. In the dream, our hotel room looked like our hotel room. I lay on the bed and prayed, asking God: Of what is the earth trying to cleanse itself with this fire? What purification, what form of absolution, are we halting when we artificially extinguish these flames, instead of letting them run their course and burn out as they intend? Cas evaporated from the dream. I sat up, alone, and looked into the mirror: I saw, as it rippled and blurred, that Charles Manson wanted to communicate with me. The hotel room began to swim around me. I felt that someone was coming at me—coming for me. I felt myself begin to lose control, to lose consciousness within the dream. You are someone else/ I am still right here.

“Manson?” I asked—an expression of familiarity that continues to disturb me even now. “Is that you?”

And all the voice said was NO. It was not the kind of “no” one utters to answer a yes-or-no question; it is the type of NO an authority figure hands down in order to deny permission absolutely—the kind that cannot be surpassed or negotiated against. I don’t think it was Charles Manson’s voice; it was both silent and too loud for the sound barrier. As that NO reverberated through my dream, and through my body, I awakened with a gasp. Cas was asleep next to me in the darkened room, our snoring dogs snuggled around my pregnant body. I grasped the white-gold crucifix necklace that Cas had given me the year before Christmas, then groped for the rosary that I had worn to bed—a treasured possession given to me when I was five years old. As I felt for it, I realized that it was now broken in two places, and that pieces of the bottom part, containing the crucifix, prayers to the collective Trinity, and earliest Hail Marys, were scattered under me on the bed.

***

Several times during our marriage, Cas pointed out that when I was in certain states of mind—usually focused ones—the lights in whatever room we occupied would turn themselves on and off, repeatedly. Sometimes this happens with other fixtures, too, such as faucets. Or electronic appliances. I usually did not notice it until Cas interrupted whatever I was doing, to point it out to me.

Partly due to exchanges like that, Cas regularly referred to me as a witch during our marriage. He often described me, quasi-affectionately, as “witching” people and things. It was certainly not the worst thing he ever called me: less than a year ago, he stood in the street and screamed, “You fucking cunt, I hope you die,” at me, while holding our infant daughter. He was angry because I had told him—quietly and carefully, as one learns to do with men like Cas—that he would indeed be legally compelled to pay child support when we divorced. “I’m glad I got rid of your stupid fucking garden, you filthy whore,” he leered at me, during a separate conversation around the same time. During the last year of our marriage, he had thrown away about twenty pots of herbs and flowers that I had grown from seed. My mother had gifted me the seeds, soil, and pots. Cas had initially brought a little cart home for me to keep the plants in. But, as the garden began to blossom, Cas increasingly considered it a frivolous and inappropriate use of my time and energy.

Perhaps it’s true: I am a witch. And I am finally beginning to step into my power, in part by honoring my connection to the earth—my abilities to create, nurture, and sustain life. I am better protecting myself and cleansing my spaces of destructive influence. But definitions of witch are nebulous, fraught: Manson instructed the women who carried out the Cielo Drive murders to “leave a sign” and to “make it something witchy.” This is how they came to write PIG on the door in Sharon Tate’s blood, after she and her infant died while she screamed for her mother, fading out under the brutality of these women and the man they followed—the man, some might argue, under whose spell they had fallen. Full of broken thoughts/ I cannot repair.

***

In 2008, I spent Labor Day Weekend with my friend Gaitree. We ran a few errands, went to random places. On three separate occasions in the same day, birds appeared directly in our path, dead and decapitated.

I do not want to phrase it that way—that they appeared. But I am not sure how else to say it. We were walking, and the path ahead was clear, and then suddenly we would nearly fall over ourselves and each other trying not to step on the dead bird that was suddenly underneath our feet.

We wondered if a cat had torn off the heads off of the birds. We told ourselves, and each other, that that had to be it. Neither of us had seen any cats.

Unnerved, we mentioned the odd sequence to Gaitree’s parents, who explained that, on the Vedic calendar, we were about to enter a time of upheaval, tumult, and destruction. The earth was going to cleanse itself, they said, but a lot of suffering, war, disease, poverty, and other problems were the route to that cleansing. A lot of people are going to die, they said. Gaitree and I were terrified. Her mother said that the sign was perhaps shown to us so that we would not need to be so afraid—so that we would understand that what was about to happen would have a purpose.

***

After Cas’s public threat, my divorce attorney advised me to file a police report for harassment. She forwarded me police reports from prior years against Cas, which she had obtained from several different local police departments. Several of the reports detailed Cas’s history of violence. Women I didn’t know contacted me unsolicited to share stories of violence, of injury at his hands. Unnerved by these revelations, I asked my friend Saumya, a religious scholar at Harvard University and ordained clergy, about possibilities for spiritual protection.

“I think even if they did arrest him for harassment, it probably wouldn’t be enough for any sort of meaningful conviction,” I said. “Like, I’m not sure it will actually solve anything, and I’m not sure it’s worth the risk of making him even more erratic and volatile. I have a daughter to protect.”

“I understand,” she said. “And you have a self to protect, too. This must be terrifying for you. But Fox, listen to me: even if the police can’t do anything right now, you do have a system in place to protect you. You have a justice system. Hear what I’m telling you. You’re going to be kept safe.”

A few months later—on the first day of March 2020—a red-breasted robin flew into the window next to my front door. His neck broken, he dropped dead onto the front porch. I was at home, but didn’t recognize the sound for what it signified. I thought a local religious zealot, who throughout my life has occasionally attempted to convert me, might have stopped by, knocked, and given up when I didn’t answer. I don’t know why I thought that, or why the thought didn’t seem strange or upsetting to me. I found the bird that way, a few hours later. At first, I thought I was going to have to kill it, to put it out of its misery. As I lifted him off of the floor, the angle of his neck indicated that he was no longer in his body.

I found a shoebox, and lined it with tissue paper and plastic bags. I put the shoebox into yet another plastic bag. I hoped it would keep him warm. I knew he was dead, but I believe it must take some time for the soul to fully pass from the body.

The next week, our national lockdowns began. A few days into quarantine, I spoke to Gaitree on the telephone.

“A dead bird showed up on my doorstep last week,” she said.

“Mine, too,” I said. “A robin. I buried him.”

“I didn’t think to bury mine,” she said. “But I hope we can stop seeing dead birds soon.”

“I hope so too,” I said.

***

In late October of 2012, I was living in upstate New York with Cas, who was narrowly avoiding assault charges while introducing me to two imminent uxoricides. During this time, the poet Elizabeth Cantwell and I were trying to write a hybrid visual-and-lyric poem about 10050 Cielo Drive and its existential significance to Los Angeles.

I made a painting for the work. I custom-mixed several different shades of red and of brown—probably about twenty, in total—and I finger-painted the word “PIG,” among other things, on a plain white piece of canvas. I felt uncomfortable as I designed it in my mind, and physically cold as I mixed the colors. I felt sick as I began to paint. I was nauseous and shaking by the time I finished.

Because I felt so physically wrong, I knew I had to get rid of the painting. But I also knew I hadn’t put myself through all of that for nothing. You suffer for your fucking art. I took a high-resolution photograph of my painting, to use for the hybrid piece.

My camera cooperated in taking the photograph. Then, immediately after I snapped the final photograph, it shut off. After three tries, it turned on and I could see that it had saved the images. I knew it must be a basic mechanical issue, but that didn’t make me feel any better.

My computer shut down twice as I tried to transfer the photos. Both times it turned itself off. I didn’t have it in me to try a third time. I had heard things about solar flares, and dimly wondered whether we were having one, or something like that. I felt a sharp pain on top of my head. I wondered if this was what it felt like to dissociate. The lights went out in the hallway. I forced myself up out of the chair, and left.

***

I have a private theory about Charlie Manson: I think when he and Charles Manson stumbled around the desert hallucinating together, the psychoactive drugs they’d taken and the purifying, sacred desert heat combined to bless Charlie Manson with a vision. I think he looked into Charles Manson’s eyes and saw himself—a man who shared his name, his age, and the more general characteristics of his physical appearance. I think Charles Manson told Charlie Manson, wordlessly, about his plans for the future: the race war he wanted to start, the tyrannical power he intended to seize. I think Charlie first saw a recognizable kind of pleasure in Manson’s eyes when their trip started, but then, as future events unfolded in tableau before Charlie, he saw that pleasure twist and mutate into narcissistic sadism, into something psychotic, something most of us can’t fully understand and so we call it evil. I think that Charlie Manson was looking into a mirror forged in hell, and that he realized if he didn’t get away now, Charles Manson was going to reach right through, grab him by the throat, and pull him through the looking-glass, past an event horizon he did not want to cross but knew he could. Perhaps, on the other side of this transparent portal, he saw the body of a woman like me, hurt in the ways that Cas hurt me, killed in the ways Cas threatened to kill me. Is the significant difference between a man like Cas and a man like Charlie simply that Charlie chose to run away from his violent potential, rather than towards it?

And you could have it all/ my empire of dirt.

***

It’s become de rigeuer in secular fashion for young women to brand themselves, especially on social media, as witchy. They don’t always mean something as religiously or culturally specific as Wiccan or Bruja or Occultist. They sometimes mean, more broadly, that they are spiritually empowered and enlightened. They sometimes simply mean, with less articulation, that they are powerful. And, of course, the cultural trope of the sexy witch has been vacillating through mainstream popularity for decades now. I think this is perhaps, in part, because women in our culture are so often reduced to their sexuality in a way that’s intended to degrade and control—a fucking bitch (literally, a dog in heat) or a fucking cunt (literally, just a body part to be used for a single purpose, by a man, and then discarded, by a man), both of which Cas called me in front of our daughter on more than one occasion. We are so often told, in daily circumstances and quotidian language that our bodies are not our own, and that a man can sneeringly wrest agency from us to prove it—that we sometimes forget, as a cohort, that taking control of our own bodies and sexualities is only one small aspect of stepping into our full power. Bodied autonomy is only the first moment of the transformation we have begun to come together to enact.

Seeing me as a “witch”—a woman whose energy could literally or figuratively light up (or darken) a room, call familiars, bring her dreams of things yet to unfold in gorgeous, Technicolor detail—didn’t stop Cas from grabbing me by my hair and licking my face to degrade me, when he was angry and drunk and wanted to punish me for “disrespecting” him by leaving the crock pot dirty in the sink overnight. It didn’t stop him from threatening to smash my laptop, or throw food all over the walls in a fit of rage and then force me to clean it as punishment. For him, my spirituality was a bangle, a parlor trick, a kitschy figurine purchased on the boardwalk.

I needed to learn how to access and wield that spiritual power myself, so that I could see and understand myself as powerful. Cas wanted to prevent that: he didn’t want me to have any recourse against the physical intimidation he presented, or his institutionalized privilege. When he sneered at me, tauntingly, “You’re a cunt,” he meant that he had the ability to obliterate my identity and replace it with whatever he cared to write in the blank space he’d created. During our marriage, he told me several times that because he “only” called me cunt “a few times a year,” that I needed to learn to live with it. He told me that calmly, in a tone that could have been mistaken for conciliatory by someone who didn’t understand the actual diction leaving his mouth. I’d seen him as a protector, at the beginning of our relationship; I didn’t realize until it was too late that the price he intended to exact in exchange was ownership of me, and my body.

***

For women, for non-binary people, for people of color, for queer people—those of us with marginalized bodies, whose entire complex human identities are often oppressively reduced to one or a few aspects of our physical bodies—because to reduce us to those and to institutionalize those definitions is a form of total domination of our bodies, our selves—our systems of faith are our justice systems. Our ancestors, spiritually purified through the rituals of death, stand behind us and help us. Because they, too, have lived with their bodies through the experience of our institutionalized justice systems failing us so frequently. And, as Audre Lorde writes, though our silence will not protect us, “for every real word spoken, for every attempt I had ever made to speak those truths for which I am still seeking, I had made contact with other women while we examined the words to fit a world in which we all believed, bridging our differences.”

Because of traumatic bonding, and because I grew to fear the man I loved, it took me a long time to learn that I did not need to persuade Cas of my power; I needed to persuade myself. And I could not do that by remaining silent, even when I realized in terror that the center had not held—had, rather than holding fast, shattered into celestial artifacts that whirl lonely through the cosmos, tearing through the sky as they seek & seek & seek until they burn themselves up, or collide with something larger and create further oblivion. And when I realized that I was too exhausted to keep trying to hold on to any of those furiously tearing fragments of what the center of my universe once was. That the center was not coming back. That what I believed to be the center would never exist again—had possibly never existed, except in my mind.

***

I still dream, sometimes, about the little girl who was taken away from the Bird House. She was obviously unstable, but what happened to make her that way? Why did she think her adoptive parents wanted to kill her? Did she really need to drink the blood of a sacrificial animal “for strength”? Against what? If she could call birds, could she also talk to cats? In many religious traditions that incorporate animal sacrifice, it is believed that specific animals, for spiritual reasons of their own and out of cosmic love for human beings, volunteer for the job.

Why, in the end, do witches call spirit familiars? We think of cats and birds and predator and prey, as mortal enemies—not unlike the way we have accepted the idea of two different “species” of women and pitted them against each other. Blonde and brunette. Madonna and whore. Cats and birds are often presented in a similar dichotomy, though both are associated with the feminine. Cats are presented as an archetypal aggressor—ruthless, stealthy, beautiful, slinking, intelligent, vicious—while birds are stereotypical victims—gentle, beautiful, stupid, fragile, vulnerable. But consider, for example, the cassowary. Consider the sackful of kittens sunk in a lake. Perhaps witches call both cats and birds because we understand all too well what men have done to them. And perhaps they understand this too, which is why the familiars we call will protect us. And the way in which they protect us is very special, though not entirely dissimilar from the covenant that humans have shared with many species of animal for thousands of years: they are willing to sacrifice themselves for us. If we need them to, they would spill their own blood in order to defend us. They spring from the same earth that nurtures us as we nurture it. That provides sustenance and gives us limits when we are transgressing too destructively as a cohort. By tooth and claw and spilled blood, they do their best to keep us safe in a world that is hostile to our bodies. And so, you see: my belief system is not singularly my protection, or my community, or my faith, or my understanding of sacrifice: it is also my justice system. And, because it bears a name that identifies my power, both to me and to others, it is also a source of my power. Come with your torches. I’m not afraid. I live in the Shadow Hills, where it’s always fire season.

Author’s note: Some of the names in this essay have been changed to protect the privacy of those mentioned. Additionally, some of the names in this essay have been changed to protect the privacy of their victims.

Citations:

[1] Winnifred Chapman was Polanski and Tate’s housekeeper. She found the victims’ bodies at 10050 Cielo Drive, the morning after the murders took place, and telephoned the police.

[2] Chandler, Raymond. “Red Wind.” 1938.

[3] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2873555/

[4] https://www.webmd.com/balance/features/negative-ions-create-positive-vibes#1

[5] https://inspiredliving.com/surround-air-ionizers/negative-ions-serotonin.htm

[6] Worrall, Simon. “How 40,000 Tons of Cosmic Dust Falling to Earth Affects You and Me.” National Geographic. January 28, 2015. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2015/01/150128-big-bang-universe-supernova-astrophysics-health-space-ngbooktalk/#close

[7] Schrivjer, Iris and Karel. Living with the Stars: How the Human Body is Connected to the Life Cycles of the Earth, the Planets, and the Stars. Oxford University Press, 2015.

[8] Anolik, Lili. “How Joan Didion the Writer Became Joan Didion the Legend,” Vanity Fair, February 2016.

Fox Henry Frazier is a poet, essayist, and editor who currently lives in upstate New York.