BY KATIE TWYMAN

The nurse stationed outside of my door is silent and still, but I know that she’s there. My roommate knows she’s there as well, and she’s angry as hell about it. I watch from my small bed on the other side of the room as she shrieks and hollers. Her dark skin is flushed to the purple-red of a new bruise, swollen with blood. Her shoulders are tensed and her short black hair is pulled tightly against her scalp into a ponytail. She is seething. My knees are pulled close to my chest as I stare out across the room.

It’s my first night in the adolescent psychiatric ward. I spent all morning and all afternoon waiting in a small room in the ER. Much of my time in the emergency room was wasted on half-hearted text messages and phone calls to various friends, mostly reciting the same few sentences again and again—"I’m safe, I promise;" "We’re still waiting to see someone;" "My mom’s with me." I extended and receive reassurances, both in turn. The emergency room felt secure and familiar, almost like coming home at the end of a long day. After all, I had anticipated my stay in the psych ward for weeks. I even looked forward to it on nights when the gashes on the inside of my arm were particularly deep and idea of fetching the old prescriptions from the medicine cabinet was particularly appealing.

Now that I’m actually in my assigned room, what I’d treasured as gems of hope feel tiny and worthless. I clutch my pillow to chest and hide my face in it. The pillow is one of the few things I brought from home. It still smells a little like my family—like squishy leather chairs and dusty shelves and sleeping dogs. I feel like crying. I feel like carving up my arms like a Christmas ham. The worst of the existing cuts on my arm throb a little bit at the thought, excited at the prospect of company, but there’s no way in hell I’m finding something sharp in this place. My bed frame isn’t much more than a large wooden box—no screws or nails anywhere to be found. The small wooden desk and chair at the foot of my bed are the same. Whoever designed this room thought about people like me.

Besides, my new roommate terrifies me. She is prowling throughout the small bedroom like a caged tiger, snarling at the hospital staff and taunting them. I’m convinced that if I so much as glance at her, her attention will shift from the nurse sitting still as a statue outside our door to me, so I stare straight ahead at the wall. Sleepy waves of deep plum and blueish teal swell and curve along the wall and I slump further and further into my thin mattress. My eyes feel heavy; my head feels heavy; I feel heavy. My roommate is throwing her things into the hall, and the nurse sounds like she has finally been coaxed into action. I am light-years away, bobbing through the murky fog in my head.

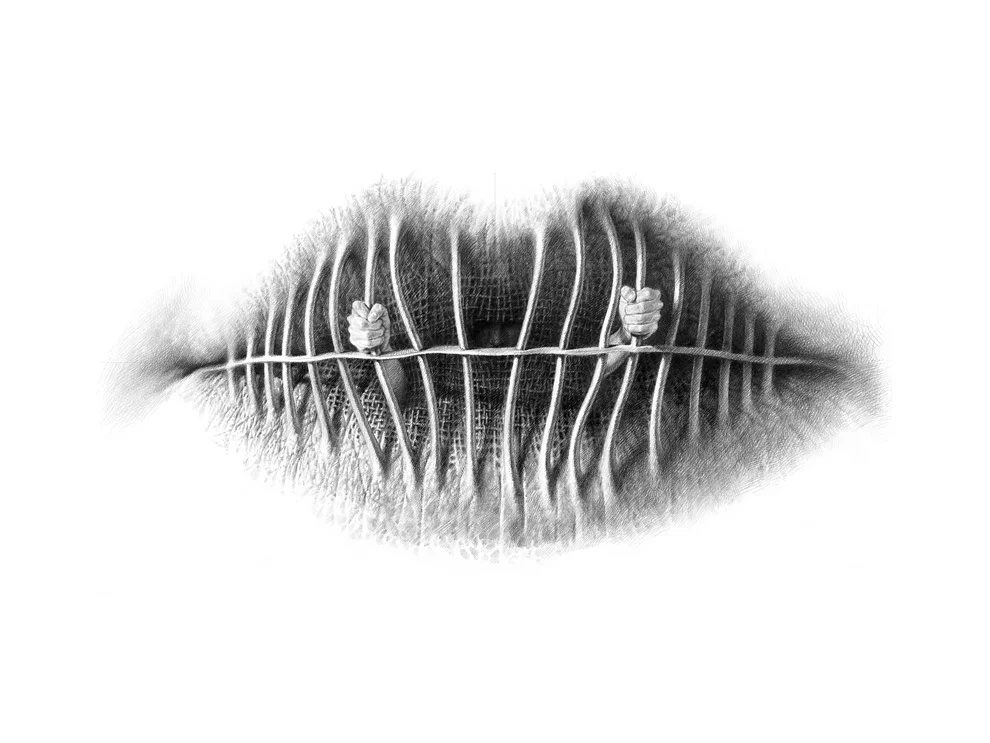

In a way, I’m jealous of my roommate. She screams and shrieks and screams again, naming each thing that angers her in turn and demanding it be fixed. She’s honest in a way I couldn’t even dream of.

Panic attacks had haunted me my entire life; my whole family had witnessed the spells of anxiety that reduced me to shaking and sobbing. My depression, however, had been my secret alone. I hid my self-loathing as carefully as I hid the scars on my arm, tucking both carefully out of sight. But some things grow best in the darkest places. By the time I asked for help, I only barely qualified as functional. I slept most of the day, only waking up when my family insisted on it. I spent every night holed up in my room. I unearthed the stolen knife from between the mattress and the box spring. I pressed and dragged it against my skin until blood bubbled up; I did it again and again until my whole arm was pink and red. Even at my most open, I did everything possible to spare my family from the full extent of my illness. I didn’t mention how I slipped out of school in the middle of the day just to have a moment alone with a razor blade, and I most certainly didn’t mention how I fell asleep to thoughts of downed pills and hanging ropes. I mentioned none of it until I was terrified to be left alone with myself. I wrote a letter to my mother and left it for her to find on the desk. I was hospitalized within two days.

In my new room, I quietly admire my roommate from under the thin sheets the hospital provided. I wonder if her throat burns from all that yelling. I bet it feels raw and satisfying. The nurse is in our room now, assuring my roommate that they can talk about whatever needs attention in the morning. After a little more persuading, my roommate finally agrees to call it a night. The nurse looks relieved, and so does my roommate. They both got what she wanted.

The same isn’t true for me. Our nurse turns to me and asks if I need anything, but I look down at my hands, which are clutched in my lap. "I’m okay," I say, barely speaking above a whisper. The nurse offers me a soft smile and glides out of the room. I lie in bed and replay the nurse’s offers again in my head. There are plenty of things I need, sure, but I don’t have the nerve to ask for a single one of them. Instead, I spend the rest of the night staring at the painted walls and listen to my roommate’s deep, even breaths until I can’t keep my eyes open any longer.

Katie Twyman is a lover of manatees, Hagrid the Half Giant, and other large squishy things. She lives in Minneapolis, where she runs Uplift, a nonprofit dedicated to combating online sexual violence through education and advocacy. Her writing also appeared in the young adult biography This Star Won't Go Out: The Life and Words of Esther Grace Earl, where Twyman is listed as a contributor. This Star Won't Go Out appeared on the New York Times bestseller list and won the 2014 Goodreads Choice Award in the “Memoir & Autobiography” category. You can follow her at @katiefab.