BY NINA PURO

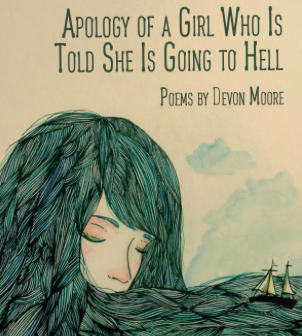

I interviewed Devon Moore, author of Apology of a Girl Who Is Told She Is Going to Hell (Mayapple Press, 2015).

I’ve known Devon since grad school, and I was overjoyed to see how her work—which has always been fantastic—has grown. This book is visceral and dynamic, rife with rich images and strange settings, “spaces that are theaters for the soul” (Bruce Smith): oceans and dreamscapes full of chucacabras, attics and deathbeds. There’s a wine-dark, pensive intricacy in Devon’s poems that left the tang of metal at the back of my tongue. There’s an unflinching eye, a resolute grittiness that plumbs longing, shame, and girlhood in America.

The following interview was conducted via email.

Nina Puro: There are no sections in your book, but there is a clear narrative arc—why did you choose this structure?

Devon Moore: When I was constructing the order of the poems in the book, I considered creating sections, but it intuitively felt like the wrong thing to do. I think a large part of the book’s project is to create/recreate a journey of self discovery – and all fuck ups and interweaving influences along the way – and to separate that out would have run counter to the “interweaving” part of that project.

Also, as my friend fiction writer Mikael Awake pointed out to me a long time ago, “we’re story people.” The narrative arc reflects that storyteller impulse in me.

NP: I’ve noticed a common perception the speaker is the poet that seems tied to gender. Your work seems partially based on biographical detail I happen to be privy to, or from the perspective of others close to you, e.g. family members…yet often told in third person (“the girl,” most frequently)— there’s a removal, a disassociation, a rupture between who you are and who you were. Was this conscious?

DM: That’s an interesting question. I think if I read the book as a journey of self-discovery, the use of the third person perspective calls attention that “rupture” between who I was and who I am. What I was more conscious of, though, was drawing attention to the constructed and imaginative nature of these poems. In most poems I draw pretty explicitly from autobiographical details as you pointed out – like the death of my father for example – but I also recognize that the speakers in these poems are not me (at least not fully) and they don’t have to be me. I think once I acknowledged that, it did away with a lot of the pressure to represent “Truth” absolutely, and instead it allowed me to construct more of a platform to communicate emotional truths, to take more interesting perspective and imaginative leaps in service of that, and to find more joy in the language I was using.

When you use autobiographical detail, to what extent are you performing or commenting on this— “All this pathos looks the same. Even if she’s not / the one who jumped off a bridge, she is” and to what extent are you genuinely trying to articulate and understand the past (“the person inside who keeps drawing herself with chalk”)? Are they different concerns?

In both of the examples you chose, I’m using the third person perspective. As I mentioned earlier, I felt that allowed me some distance to play in the space between autobiographical detail and poem as constructed art. But thematically I think you’re right to see some kind of commentary on how identity gets constructed, on how all these experiences have contributed to or created theaters upon which I’ve become the person that I am – and how those experiences have acted upon me, and how I’ve in turn acted upon those experiences, if that makes sense. In poems where I use the “I” voice, I think that theater of self-development is playing out as well. Those poems acknowledge, yes things happened to the speaker, sometimes bad things, but the poems often forefront not so much the thing that happened, but how the speaker made sense of it. I don’t want the “I” or “she” in my poems to be passive victims or self-pitying – I want them to enact a kind of strength made possible through self-interrogation, empathy and understanding.

How does girlhood/ gender play into your work?

I think what I just said about not wanting the speakers in my poems to be “passive” – and wanting them to have strength in their “empathy” and “understanding” – is speaking in some ways to how my poems respond to the gender stereotype of women being the weaker sex because they are more emotional than their male counterparts. In these poems emotion is power.

Also, I was asked recently to talk a little bit about my title. “Who is this girl? And why is she going to hell?” And my response to that question speaks directly to the gendered nature of my title and also my book cover. The title, Apologies of a Girl Who Is Told She Is Going to Hell, was taken from the title of one of my poems in the collection. I think the book functions as a kind of genuine apology in some ways. For example, in the poem “Patricide,” the speaker apologizes to her dead father for not having killed him when he was in so much pain and reenacts going back in time to ease his suffering. But as you read the book and the title poem, there also exists a kind of “sorry, not sorry” tone (to borrow a phrase from the social media-verse) – a kind of commentary on apologies and how girls are raised to be far more apologetic than boys, even when they have nothing to apologize for – and a sense of a speaker who is finally learning to stand up for herself. I was thinking about how gendered my title and cover art are recently, and I felt a moment of worry. I wondered if the book would get immediately dismissed as one of fringe-interest (especially in a world of literature where poetry is already treated as a fringe-interest), but since women make up half of the population, and men are sons or brothers or lovers or fathers of women, I hope the book cover won’t immediately exclude my book from male interest. The fact that I need to worry about that is fucked up.

The speaker of the title poem is a projection of my adult mind trying to reconcile the confusion I felt during some of my childhood experiences with a born-again Christian, but also I think it speaks to multiple childhood experiences of feeling really confused by adult expectations in general. I was an inquisitive child, and I was always saying things or asking questions that got me into trouble (how rooted that might be in gender norm expectations that little girls should be passive and submissive is something I’ve been wondering about). I think in many ways the speakers of my poems are in that kind of liminal space – reconciling their past selves with their present circumstances and the desires of the people around them – and not always having the easiest time of it.

There’s also the difficulty of getting along: you segue from family members to partners & back again. How do they differ & relate?

That is definitely one of my preoccupations, although I might have called it a pervasive loneliness rather than a “difficulty of getting along.” While the nature of romantic relationships differ in some obvious ways from familial relationships, it is in those encounters that I have learned the most about myself and it is in those encounters that I can enact an emotional and intellectual experience for my readers. Also, in my daily life I think a lot about how the various neuroses/ways of coping that are familiar to me because of my family relationships have gotten replayed in my romantic relationships. It’s scary to think how much of a bearing the habits and familiarities generated in childhood have on the success or lack of success of ones’ romantic relationships (and even friendships). I don’t necessarily think I comment on that in explicit ways in my book, but I think the juxtaposition of those poems next to one another, and the reoccuring sense of a speaker making sense of it all speaks to that implicitly.

The role of time in your work has always been of great interest to me. It unspools, loops back on itself, and most frequently goes backwards. Could you speak about how you came to use this as a tool and how you view it? Is it a wish to change the past or is it a facet of your framework, e.g. how you perceive the world—or perhaps embedded in both?

I have a reoccurring dream about my father who passed away eight years ago. The specific setting changes, but in these dreams I usually see him and recognize simultaneously that he’s alive in the dream (usually walking around and talking to me) but also that he’s really dead. Part of what pervades the dream is the dread in knowing that him being alive is only temporary, and at some point in the dream that dread usually comes to fruition and he dies. But as I’ve continued to have that dream over the years, something interesting started to happen. When I began to recognize the simultaneity of him being alive and dead within the dream, that recognition gave me the power to influence that. For example, in one dream I remember vividly (I tried to recreate this experience in the poem “Playing Pool at ‘Taps’”) I go into the back room of a bar where he and I had been playing pool and I find him lying down on a slab like you’d see in a morgue and I recognize that he’s died. And then I recognize that because it is my dream I have the power to bring him back. As soon as I think this, his chest begins to rise and fall. I then, in my dream (not in the poem), I play out a kind of necromancy where I will him dead and alive again and dead again, watching him breathe and stop breathing and breathe again. I think that is similar to the relationship I have with time in my poems. In real life I can’t turn back time or death, but in the world of my imagination and in the world of my poems I can – and in doing so work something out in the past that needs to be worked out.

I am highly curious about the chupacabra and the roles of animals in your work, generally. Is it a myth, a joke, a signal to something private, or all of the above?

Ah, the chupacabra. Several years ago I read an article about a man who claimed to have captured a chupacabra and taxidermied it as proof. For some reason it captured my imaginative interest, and spoke in some ways to my relationship with death and the resurrecting power of my poems. I’m fascinated with cryptids – the mythological animals found in different cultures – and how they function is an indexes of fears (in the case of the chupacabra) but also as indexes of magical and imaginative thinking (like unicorns).

In my current writing, so poems that aren’t in this collection, but will be in my second collection (fingers crossed), I’ve moved away from the cryptids and have included a lot more “real” animals – but still using them in ways that evoke magic, wonder and a little bit of creepiness.

What poets & artists most influenced this book?

This is hard questions for me to answer because most of what I write is triggered after reading/hearing something – a turn of phrase, a image, an event – sometimes in poems, sometimes in news articles, sometimes in overhearing a conversation between strangers, so to do the question justice I need to list 50 people. I will say that one of my earliest, most significant influences, was Sharon Olds. I went to NYU as an undergraduate and I attended a poetry reading where I saw her read. It was the first time I ever attended a poetry reading, and there was something fierce and fearless about her writing that I was drawn to, and I credit that moment with sparking my first serious interest in poetry. A few years later, I was in a workshop and the workshop instructor said, “I’m not interested in confessional poetry in the Sharon Olds-sense of the word” – he wasn’t speaking about any poem in particular, just poetry in general. Thinking about “confession” in poetry and the contentious place confessional and “accessible” poetry have within the poetry world is something I thought about explicitly as I wrote AOAGTSIGTH, it’s something I still think about. I think one poet who helped me in thinking through these concerns was Denis Johnson. I remember reading his poem, “The Flames,” and being aware that his poem was both describing an event that the speaker is living through (he’s traveling on a Greyhound bus), but Johnson is writing it in such a way that it is surprising and transformative, imbuing the event with a kind of awe-struck, other worldly significance – something which, when I go back to Sharon Olds’ poetry (take the poem, “The Race,” for example), I see her doing, too. When I was a beginning writer, I wasn’t sure what to make of the words of that early workshop instructor, but now I think they were reductive. One thing I’ve learned is that it’s good to know when not to be influenced.

What did you eat and listen to when writing this book?

Since it was written over a five-year period, I’m sure I consumed a lot. Knowing my eating habits, I’d bet there were considerable amounts of baby carrots, greek yogurt, apples and chocolate chips going down during the drafting of some of these poems (not necessarily all at the same time). I know one of the poems in the collection I wrote at my friend’s kitchen table while we were baking a cake in the shape of a sheepdog. So, some sheepdog cake got eaten.

In terms of what I listened to, I have a hard time writing to songs that have lyrics, so I play a lot of instrumental music from YouTube videos when I write. Or sometimes I write at home in silence. Or out at a coffee shop surrounded by the whirr of espresso machines. If you have any suggestions for music without lyrics, I’d love to hear them.

Editor's Note: This feature appeared on our old site.

Devon Moore hails from Buffalo, NY with a lot of time spent growing in Wilmington, NC. A former high school English teacher at Dewitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, she currently lives in Syracuse, NY where she teaches writing at Syracuse University and SUNY Oswego. She received her MFA in Creative Writing from Syracuse University. Her poems have appeared in Gulf Coast, Harpur Palate, Meridian, The Cortland Review, and others. Apology of a Girl Who Is Told She Is Going to Hell is her debut collection. You can visit her at www.devonjmoore.com

Nina Puro’s work can be found in Guernica, H_ngm_n, the PEN Poetry Series, and other places. A member of the Belladonna* Collaborative; the author of a chapbook, The Winter Palace (dancing girl press, 2015); and a recipient of a fellowship to the MacDowell Colony.