BY ALEXANDRA FORD

David Bowie was born two days after me and thirty-nine years earlier.

When "The Next Day" was announced on David’s birthday back in 2013, I remember crying for an hour while listening to “Where Are We Now?” on loop, half under the covers in my bed in Brooklyn, memorizing the lyrics. I was in awe that he had returned to music, that he had kept it so secret.

I did the same when Blackstar was announced.

I’ve been waiting for the vinyl to arrive in the mail. It was supposed to arrive before the release date, before David Bowie’s 69th birthday. I was supposed to put it on the turntable and turn up the dial, lose myself in the joy of another unexpected album.

My in-laws ordered Blackstar for me for Christmas, while I was still living in America, in the city where David Bowie recorded Young Americans. Now I’m waiting for the mail from behind a doorway in a British house, where I moved just two weeks ago with my husband, and there is a feeling of unfillable emptiness.

*

Nothing has changed. Everything has changed.

*

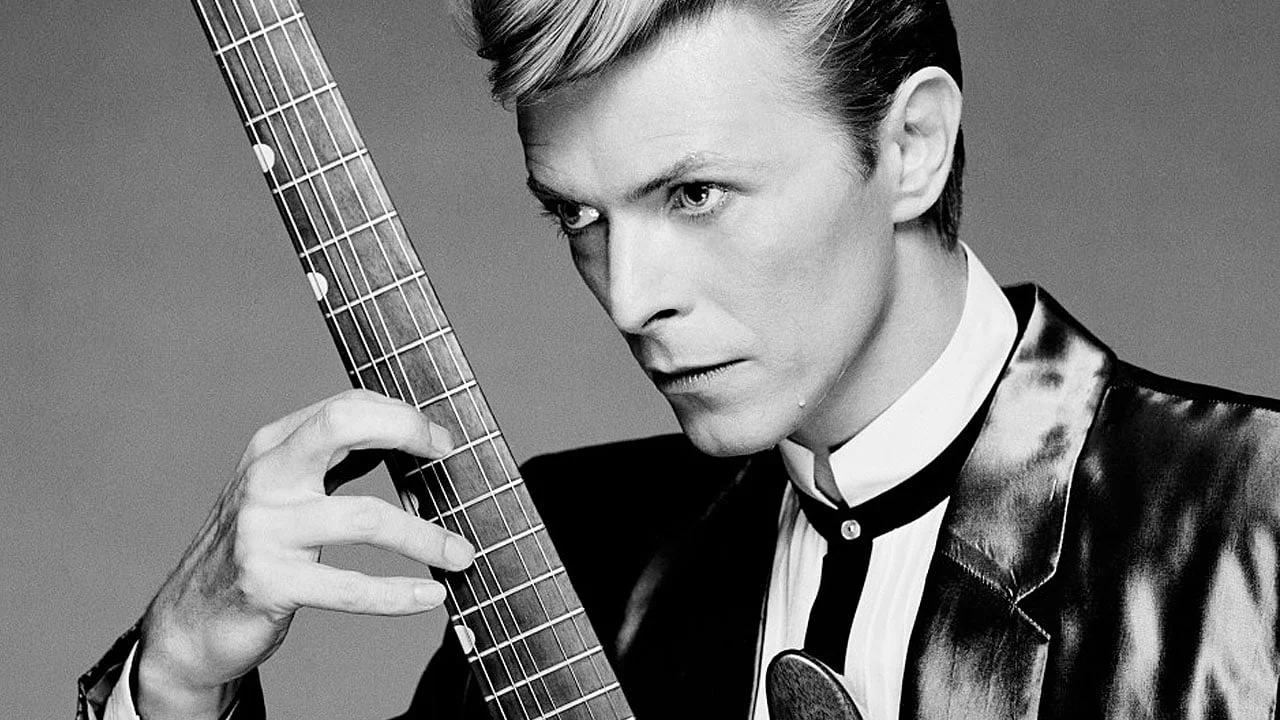

When I was eleven, I sat cross-legged in my parents' living room, glued to the television, fascinated by a skinny blond man twirling crystals in gloved hands. I watched the smooth juggling motion, the way his glam-mullet blew away from his face in wisps of platinum and blue. I watched his lips curve over his perfectly crooked teeth and blushed at the unforgiving tightness of his pants. I heard the soft rasp of his voice crooning over his own reflection in the glass.

My stomach fell through the floor. I think I hit puberty that day.

I waited for his name to appear in the credits. Afterward, I begged my father to take me to the record store. I expected to find the Labyrinth soundtrack. I didn’t expect to find an entire row with black typewriter letters stamped on white plastic, dedicated to David Bowie.

*

David’s first wife, Angela, recalled an evening in the backseat of a limo with David after the Minneapolis news at six in 1974 declared that an alien spacecraft had landed somewhere in Michigan.

I can imagine the chaos—news anchors trying not to cause widespread panic, hazy photographs of UFOs on the television screen, thousands of Americans with their eyes on the sky, waiting.

The eleven o’clock news came on and told viewers that “the prime-time news crew had perpetrated an irresponsible and inexcusable hoax, and had therefore been dismissed from their jobs. No UFOs had landed; no aliens were in custody, dead or alive; the United States Air Force had positively not engaged or intercepted any craft whatsoever in the skies above Michigan; and that, officially and absolutely, was that” (from Angela Bowie’s Backstage Passes).

She talked about David, his face pressed against the eyepiece of the telescope that was set up through the sun-roof of the limousine, peering into the sky for more signs of life. Angela implied that he wasn’t awed by aliens in a scholarly way, but “like a vampire.” He wanted to be an alien, be seen as a figure resembling his alien/Icarus-character in the movie The Man who Fell to Earth, inspired by Bowie, directed by Nicolas Roeg. Rewritten again by Bowie for his Off-Broadway play, Lazarus.

The Man Who Fell to Earth was weird like a lot of 1970’s movies are weird—full of desperation and an excess of unshaved genitals. It referenced Bruegel’s painting of the fall of Icarus, only Icarus was no longer a demigod with melted wax wings, he was David Bowie/Thomas Newton the alien, selling his planet’s science in order to find the money to get home to his space-family.

*

One summer, the Discovery Channel came to my hometown to examine a fast-growing series of UFO sightings.

The first UFOs came early in the summer. My mother called it the Oxford Valley Mall sighting—people in the parking lot watched strange lights move in the sky.

The second sighting happened just down the street. A woman and her teenaged daughter were pulling into their driveway when they glanced up at their neighbors’ house. A strange, triangular craft hovered above the roof. It made no noise, but its anterior lights formed a radiant blue “V.” They watched it from their neatly paved driveway until it soared over trees in the distance and zigzagged into the night.

There was speculation that the craft was some unreleased military project. But, if that were the case, why would it be flying low over the manicured lawns of suburban Philadelphia—twenty miles from an all-but-closed-down Naval Air Base?

For many nights, I stepped out into the yard humming “Hallo Space Boy” or “Life on Mars?” with my little dog on his leash. I stuck as close to the house as possible and kept my eyes on the sky.

*

It’s been more than a decade since I woke up underneath David Bowie.

Back then, my friends and I would move from dorm to dorm with red solo cups filling and draining and filling again. After eating the grapefruits out of the buckets of jungle juice, we’d head home—occasionally in the arms of another inebriated college student.

Some nights I’d bring her home. The first night, we stumbled into my room, trying not to wake my roommate. In the fashion of inexperienced drunks, we crashed into the sink, the trash can, and my desk before climbing up into my rickety metal bunk.

She whispered something in my ear about eyes on the ceiling, then curled up in the crook of my bare elbow and fell asleep. I buried my nose in the flowing spread of her hair on my pillow and closed my eyes.

“Oh, God!”

I jerked awake at six in the morning to the harsh sound of her shout and fell out of the bed, five feet onto the carpet below.

“Oh my God, are you okay?” She leaned over the edge of the bed and her red hair fell over her shoulders and framed her face.

“I’m fine,” I said, rubbing the back of my head.

“Why do you have a poster of David Bowie above your head?”

“There was nowhere else to put it.”

After a while, she became accustomed to waking up under David Bowie too—we’d lay there and giggle at the thought of sleeping underneath an androgynous, sometimes bisexual rock star.

The boys I brought home responded differently. I remember one particular boy who used to steal my bed for naps while I was in class. I overslept one Wednesday morning and woke up to the creak of someone climbing up the bunk.

I scooted toward the wall to give him room.

He kissed me gently on the cheek and said nothing; he just laid there next to me, staring into David Bowie’s mismatched eyes. He reached his arms under the covers and put his hand on my waist. I felt uncertainty in his fingers as they inched higher.

“Fuck,” he said softly.

“What?”

“How am I supposed to touch you with him staring at me like that?”

*

My father bought me tickets back in high school for the Reality Tour, but only, I think, because he knew there was no stopping me.

My father made it clear that he was not a fan. Sure, he enjoyed The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, but who didn’t?

David Bowie had a premonitory sense for music—or maybe he was just caught up in the movements of the world. You can listen to Ziggy Stardust, the skinny man in women’s clothing fresh on the music scene, grow into Aladdin Sane, the man he evolved into when “Ziggy [went] to America” and found fame and drugs, and his transformation into the Thin White Duke, the emotionless, cocaine-addicted superstar. You can hear how Berlin changed him, Warsaw. Age. Mortality.

I think the real reason my father wasn’t a David Bowie fan is because Bowie exploded gender expectations. He wore short kimonos and neon makeup. He was an outsider. A life-seeker. A poet. A mime.

*

I wrote my first novel for David Bowie. I hid it in one of the fifteen suitcases I moved to England with. I wrote it listening to his music. I wrote his aliens, his Uncle Floyd. I wrote his gravedigger. His mousy-haired girl. His Lady Stardust.

I wrote it all and it was terrible. I wrote it all and stole it all and left it in a box to gather dust. But I can’t bring myself to throw it out.

When I read the news this morning, I listened to “Lazarus.” I watched the video. I watched the articles pop up about his last musical breath—his farewell. And grief was soothed with gratitude.

*

Years ago, I sat on the floor with a friend, cross-legged, drunk, and stoned. We’d been listening to Bowie’s music for hours, each sharing our favorite songs and singing along—he sang melody, I sang a dissonant harmony.

We leaned back against his desk and stared up at the swirling white light of his lamp, fluorescent and bright against the dark walls and ceiling. The track changed to “Starman,” and we just sat there, stoned and selfish enough to think that we were part of the music, that the room was the music, the blaring light, the radio that perched on his dresser.

And we sang:

There's a starman waiting in the sky

He's told us not to blow it

Cause he knows it's all worthwhile

He told me:

Let the children lose it

Let the children use it

Let all the children boogie.

Alexandra Ford is a writer and sommelier. She received her MFA from Sarah Lawrence College and her perspective on art and the world from David Bowie. Her short fiction appears in Blunderbuss Magazine and No Tokens Journal. She is currently working on a novel.