BY JORDANA FRANKEL

[Reported from Standing Rock]

Jordana Frankel

For as long as I can remember, I’ve had dreams of the apocalypse. Usually, I’m doing some remarkably unremarkable task, like grocery shopping or slicing apples in the kitchen. But during one dream, I was absentmindedly gazing out the window at a blood-red lake where a sprawl of dead fish glittered from the sand banks like an aura.

I realized the time for change had passed and now I lived in a time of consequence. For me, the apocalypse was never an abrupt religious meltdown. It was that moment of waking up from years of socially ingrained malaise, my buried intuition surfacing too late. It was losing the war, having never been called to action.

In early November, I left the Northeast with my partner for Standing Rock. At home reading about the conflict surrounding the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), I’d maintained a vigilant level of healthy democratic skepticism. Though concerned about the dangers a pipeline might pose to the water supply, I’d also wondered why Standing Rock Sioux hadn’t spoken up earlier, as asserted by DAPL. I withheld forming an opinion, believing that, in order to reach some über-rational conclusion (one that didn’t impulsively align with the underdogs out of sympathy), I’d need more information. I wanted to learn the truth without entirely understanding what that meant.

Though I’d named it journalistic curiosity at the time, if I were being totally honest with myself, the pull had come from a much deeper, more unnamable place.

Police blockades prevented us from easily reaching camp, and so just before midnight on November 8th my partner and I found ourselves a cheap motel in Bismarck aiming to try again the next day. In the achy fluorescence, we drew a bath and listened to a news anchor tally up 2016’s election polls, imagining the worst for our country. When on the following morning our fears were confirmed and Donald Trump was named the next president, a feeling rose up inside similar to that which drew me to North Dakota. It felt like a call to action, though I’d never heard one before. Unfortunately, my inner compass — that thing that distinguishes “bad” from “unbearable" — had been wavering for quite some time. So long, in fact, that I’d almost forgotten I cared at all.

Jordana Frankel

I still believed that I’m just one person.

That same night Donald Trump was elected the 45th President of the United States of America, we arrived at Oceti Sakowin (Oh-CHAY-tee Sha-KO-ween) camp.

The camp sits on the Cannonball River, a tributary of the Missouri River under which the infamous 1,172-mile long pipeline would cross, and was originally known as Inyan Wakangapi Wakpa, or “River that Makes the Sacred Stones.” On the opposite bank you’ll find the quieter, but more well known, Sacred Stones camp. Today, the highly spherical stones that gave the site its name are extinct. Not since the late forties, when the Army Corps Of Engineers finished the Oahe dam, have there been the whirlpools necessary to their formation.

The land here is used to such kind of historical trauma. The First Treaty of Fort Laramie, which accorded the Sioux nearly five states worth of unbroken land including most of the Missouri River, the entirety of North Dakota, as well as the Black Hills, has been forcibly renegotiated or flat-out broken by the U.S. since being drafted in 1851. Over the next century, with the discovery of gold and other valuable resources, the U.S. further restricted Sioux lands. Today, the demonstrations at Standing Rock are both a predictable iteration of this centuries-old war, as well as an historic show of intersectional support for indigenous sovereignty and the future of our planet.

It’s history repeating itself, albeit with a fresh twist: Allies.

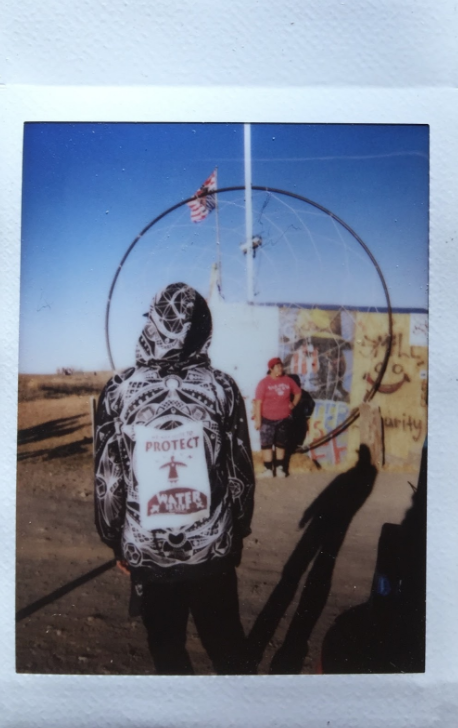

The road that leads to the heart of Oceti Sakowin isn’t dubbed “Flag Row” for nothing: Native tribes from not just the United States, but around the world, have offered their flags in solidarity. Around the sacred fire you’ll find peaceful ambassadors from all walks: Sikhs and priests, nuns and BLM supporters and members of CODEPINK. There’s a Two-Spirit camp as well, for LGBTQ people of both native and non-native descent.

Not yet knowing our way around, my partner and I pitch our tiny two-person tent near a large tipi (or teepee), home to two native jewelry makers, and a Chevy camper owned by a man named “John’ — a white, reformed logger whom I later learn is in charge of the camp’s infrastructural energy needs. Due to his job liaising between land developers and indigenous tribes in Washington State, he preferred to remain anonymous for this article. He casually points out a well-known burial mound in the distance. “See that?” he asks. “Someone’s great-great grandma is under there.” Parked atop the mound is a bulldozer.

A few campsites over, I meet Jamie Colvin from Oklahoma, here on holiday break with college classmates. She has ancestral connections to the Seminoles, a tribe forcibly removed from Florida in the mid-1800’s. Flushed with cold and frustration, she speaks of plants long extinct, their names and uses memorialized in a language she was never taught. Her assimilation into the paradigm of whiteness was — despite its privileges— nonconsensual, and so for Jamie (as for many others here with Native roots) showing up for Standing Rock is an act of self-actualization, a way to peacefully subvert both her own erasure and the erasure of indigenous peoples everywhere.

Jordana Frankel

“This pipeline is the Black Snake, and we’re the seventh generation,” Jamie says, referring to two different Lakota prophecies. The first (origin unknown) warns against a black snake that will bring destruction if it is allowed to cross this land. The second was made in the 1800’s by Lakota holy man Black Elk, foreseeing the creation of a new, worldwide Sacred Hoop — a restored connection between Earth and all humankind, not just its Native peoples. “The prophecy said we would unite the people of the world . . . Look around,” Jamie continues, desperate with hope.

The following day I attend a “direct action” meeting. There, water protectors learn techniques for non-compliance in the event of arrest on the frontline. Since this is prayerful camp, we’re frequently reminded to practice non-violent resistance, but it serves a tactical function as well by revealing the brutality of the militarized police force which disproportionately targets people with press badges, thereby keeping documentation of its excessive force from the media.

Jordana Frankel

I hear phrases like “weaponize your privilege” and “decolonize yourself,” maxims that allow white allies like myself to stand in fellowship by owning our inherited freedom — an ancillary benefit, not the human birthright it is oft heralded to be — and offering us a way to make reparations in the name of our ancestors. I am no warrior, but in this place I’m realizing that I can no longer be quiet either, and so I learn how to mobilize myself using what peaceful tools I have at my disposal. A pen, for instance.

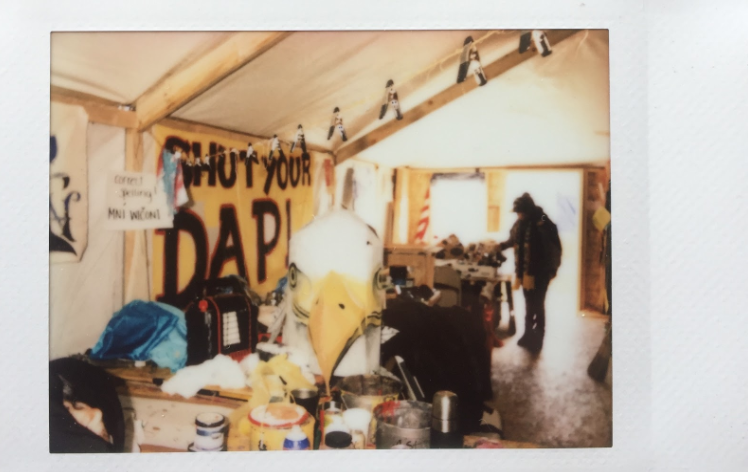

Many others here are artists and creatives like myself who, finding themselves between paid gigs, choose to offer their skills to the cause. Some, like Sacramento-based Mary Zeiser, move from one social justice frontline to the next, bringing her art and activism wherever it’s most needed.

She’s one of two women running an art space where water protectors can spray paint signs or silkscreen “Mni Wiconi” patches for those on the frontline. Peeking inside the tent, I spot a huge, handmade yellow and white paper mache eagle head — a neatly striking convergence of the art, activism, and culture that can be found here.

Jordana Frankel

Camp is collectively invigorated on the night of the supermoon, whose brightness does not discriminate, clinging to bulldozers and the sacred fire alike. A low, defensive mist skulks about. From a high vantage, only clusters of tipi poles pierce its veil. A Hopi woman holds her hands up to the pale sky, warming them by the glow. Then she touches my cheek. “Feel that?” she says to me, unable to pull her eyes away. “I have Reynaud’s — my hands are always cold. It’s that powerful tonight.”

She’s right. The tips of her fingers feel warm. The air hums and my edges feel fuzzy, as though my skin were giving off some heavy wattage. Magic is here with us---the intuitive kind that feels like an answer, or a direction. I feel a deep, instinctual need to protect this planet and its people. Shamed by this country’s history of genocide, terrorized by a future that looks no different, I am suddenly desperate for change, and if my government will not step in---will not choose to make its own reparations — I have no choice but to represent myself, on my own terms.

A friend’s father joins our campfire with news from the outside world. The Army Corps Of Engineers issued the following statement: “Construction on or under Corps land bordering Lake Oahe cannot occur because the Army has not made a final decision on whether to grant an easement." The news makes us giddy with optimism.

And then, just as quickly, the tide turns.

Sickness spreads through the camp with surprising momentum. My partner complains of a sore throat. She’s also developed a deep chest cough, two symptoms echoed by many others in surrounding campsites. “They’re spraying pesticides on us,” a young man camped nearby says, and my partner recalls how a day ago — while watching a helicopter pass overhead — some droplets had fallen onto her face. She’d thought it had meant rain, but no rain came.

Jordana Frankel

A few days later, with temperatures dropping fast and no sign that her symptoms are improving, we decide to pack our belongings and return in better health. As John strolls up to say goodbye, I notice the hills behind him are alive with movement. DAPL has chosen to ignore the Corps’ statement.

“It’s cheaper for them to pay a fine every day,” John says, shrugging.

Jordana Frankel

Both defeated and emboldened by our time here, my love and I leave camp. We’ve seen the giant that is DAPL, but in its shadow we’ve reconnected with certain basic truths that can only be understood on a visceral level, the core of which being a deep, empathetic respect for our planet and all its living, growing creatures. At the forefront, we are allies fighting for the sovereignty of our indigenous brothers and sisters. But the community at Standing Rock — the sacred circle that has been forged there — intersects many other circles around the world, including the Earth itself, all with its own story of struggle and survival. Today, I am no longer ambivalent. Where we give strength, we receive strength, and understanding this I am renewed, called to action by none other than myself.

Maybe now I can stop dreaming of the apocalypse.

Jordana Frankel's debut novel, THE WARD, (KT Books/HarperCollins) is in stores now.