(Editor's note: This interview originally appeared in TheThePoetry)

BY JEFFREY HECKER

Photo credit: Allyson Jackson

JH: Congratulations on your first book diatomhero: religious poems. I treasure how this poetry holds every religion responsible for being authentic and explores exactly what kind of turmoil/freedom of movement (of creed, language, time, space) arises in such a busy atmosphere. I’m thinking specifically of Christianity’s notion of finite resting places (blazing hot or room-temperature) teamed with Buddhist/Hindu reincarnation notions and Greek polytheistic elements. The book is a cream vichyssoise where these ingredients are available to be salted, peppered, and consumed. Could you talk a little about how the book is and is not a supplement to all religious texts?

LF: I love the word ‘vichyssoise’. It’s blonde as a Gibson girl in a mint satin evening gown, as per the synesthetic-green letter ‘V’. Definitely a word with the curls of the sun.

The title, diatomhero, is an anagram of the bible’s “I am the door”, a statement that comes full circle in the book’s final image, and applies just as much to Christ as it does to Janus. To open the doors of all myths and religions, to ‘let’ their darkness, (un)like bloodletting. At the end of the book, when Bluebeard’s chamber is opened, there’s not slaughtered women hanging on hooks, but far fields stretching out—a wide open country to fly out into ecstatically, like a heavy symphony unlocking its heavy doors and letting itself out of itself in its final movement.

As opposed, for example, to a story like Poe’s Red Death, that ends walled inexorably up in its own terror. I’m not talking about imposing one’s own will against the will of the muse/work itself, or about ‘revisionism’ or ‘escapism’, but about a deliverance seductive enough to embed itself in the text without compromising it. Like Tangina in Poltergeist saying, “this house is clean”, only it’s “this myth is clean”… but with no tricks to follow.

A supplement is a continuation. The question is whether the myth is on a blind loop, or if it’s aware of intrusions. If we took the story of Princess Thermuthis finding the infant Moses among the reeds, but put the river hag Jenny Greenteeth in his place, what would that have done to the evolution of Christianity? If Hera had given birth to Christ; if Mary had found herself with Zeus’ child, because he came to her in one of his characteristic disguises, as he came to Danae as golden rain, etc. These combinations can be perverse and amusing or they can be profound: Ariarhod and Christ falling in love, and Christ finding, in love for her, a new world outside Christianity—like Cortez, or like the iconic awe of someone who’s never left the heartland seeing the sea for the first time.

In Annie Hall, Woody Allen describes a relationship as being like a shark that has to keep moving forward or it will die—so we can apply that to myth, and of course to the myth of the dying god. If the inhabitants of a myth found themselves on a dying planet—a planet that was, of course, the myth itself—they would have to evacuate, to look for a new life in another legend. In somewhat of the same spirit, then, immigrants—drifters—from other afterlives appear as migrant workers in the Elysian Fields.

Theoretically, too, the book is written for synesthetes. And, as such, is ideally meant to be seen through synesthesia, like 3-D films are meant to be seen through 3-D glasses. And this is where the mythological blending/puree meets an ideal medium, because of course the synesthesete already has a sense of the dis/harmony of totally “unrelated” things—which are not really unrelated at all. So essentially the book is a preliminary study of synesthesia as myth and religion. I say “preliminary” because I’ve not gone near as far with this concept as I want to. diatomhero is an incomplete book, and it’s a work in progress, as all poems are. It plays with the “worlds colliding” theme, which a lot of people have of course played with, but I would like to think/hope (?) it does it in a unique way.

JH: The play turned-compact long poem makes for a jarring opening sequence which describes a manufacturing plant for souls and bodies. I love how this really kicks out the chairs from under the audience from the beginning. Readers must navigate the balance between the playful and the scarier. Everything familiar remains in the ball room but it’s simply misplaced, like hearing your favorite childhood song performed by a band of Gorgons on a harp strung with your mother’s funeral hair-do.

The willingness to travel these fissures is crucial to enjoying the poems. Was there a purposeful attempt in these afterlife sequences to balance nostalgic memory with what are undeniably horrifying dream elements?

LF: I love that Gorgon/funeral hair juxtaposition, and I love this question. I think nostalgia, or merely fantasy, is a natural retreat in times of trauma. But—again with the deliverance premise— there’s the idea that a dream is an innocent desperately trying to communicate its plight through a nightmare, rather like what happens at the very moving end of the Spanish horror film The Orphanage. Variations of this concept have often been explored in Grimm and Perrault, et al. The innocent as needing help in being extracted from the context of a nightmare, but being unable to tell anyone how to do help them. The imprisoned who have to be saved by the freer being virtuous (Beauty and the Beast), or by sheer chance (The Frog Prince.) It’s up to the rescuer to figure out the riddle. And this is perfectly apropos because it is, of course, how the process of wisdom actually works.

However, diatomhero is not about being rescued, but about being resourceful enough to rescue yourself. And about the arc as rescue, the underside of the arc that will return you to its exact opposite: a divine inevitability, a point beyond which the absence of good becomes so acute that the reality of its difference from evil is unmistakable, and no longer philosophically debatable. This, to put in the simplest terms, is salvation by default. And it takes us to a quote by Djuna Barnes, one of the most beautiful quotes of all, which I used as one of diatomhero’s epigraphs: ‘the unendurable is the beginning of the curve of joy’. I had a dream once that someone gave me that quote—the quote itself, in words—encased in an 80s style/Desperately Seeking Susanish jelly bracelet. That was the way that particular observation presented the true genius of itself to me—by literalizing itself.

JH: Emere’s Tobacconist is noted as having been originally constructed as a ten-act minimalist play, a whittling down that resulted in many sleepless nights. What sections did you extract and do you plan on producing it as theater in the future?

LF: I’m still negotiating the technicalities of the staging (and by “negotiating” I mean going over it in my own head, because nothing is on the table right now as far as production goes). Most of the acts are in fact truncated. The car accident victim who sees the bloody windshield of his car turned to a red stained glass window as he enters paradise reappears; in the extended scene Marc Chagall is there, having been commissioned to render the last earthly memory of the man into something sublime. So the rest of that scene is dialogue between those two men. There’s a monologue by Shura, the daughter of Ted Hughes and Assia Wevill, in which Shura enters—and goes wandering around—the childhood memories of the woman who found her dead and tried to revive her. There’s the blood of the slain turning white socks pink in heaven’s washing machine.

There’s more Huck Finnish adventures down the river with John and Pearl in Night of the Hunter, in which they meet all kinds of water myths, and stories, like Ophelia and the singing head of Orpheus.

Night of the Hunter (1955)

JH: Readers will invariably focus on myth and doctrine. I see those elements more like background music. They also aren’t meant to represent what they historically or even physically represent, as when somebody in your afternoon nap hands you a fork with no food on it and you thank him and simply eat the fork, which tastes like Special K (the cereal).

I also noticed a kind of Confessional coming-of-age Bildungsroman fable (The subsequent 1000 odd color photos of the rest of your life) working in this collection. It may be beside the point, but could you address some of the “real-life” challenges you may have been facing that sub-atomically got engrained in the white spaces between the ink?

LF: Dadaberry Crunch! (Why didn’t Wonka invent the Dadaberry?).

The writing of diatomhero, in tandem with several events, was accompanied the realization that there’s no such thing as “odds”, because something is only randomly likely or unlikely to happen until it happens to someone you love or to you. The concept of likelihood or unlikelihood is a consolation device—and a privilege. This has probably been common knowledge to enlightened people for centuries, but I didn’t always know it. I used to feel that there was a difference between myself and someone who had died. I don’t anymore. That’s not a fatalistic statement, it’s a statement of gratitude, because gratitude is about recognizing randomness as much as it is about celebrating and honoring blessings—because life and existence are joys to be celebrated and honored, not because you’ve made it out of the hole thus far.

One of the final images in Rorschach came from attending a dear friend of mine’s viewing. Some weeks later, I had a nightmare of her on the embalming table. But it ended with her zodiac sign (Cancer) leaving her body like a crab and scuttling off into the ocean. And then the crab ended up on the shore of the Riviera, in Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief, and climbed out onto the shore of that film, and her birthday (the 4th of July) fused with that film’s iconic fireworks scene. The nightmare had outsmarted itself and become an act of escape, of transfiguration.

JH: What classic cinema made this collection possible?

LF: I didn’t even come close to honoring the great religious films, like Larisa Shepitko’s The Ascent and Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc, though their spirit was very much an inspiration. Jack Clayton’s The Innocents. Scads of films that weren’t mentioned in the appendix. Carnival of Souls. The Virgin Spring. There are so many it would take far too long to try to list them. David Lynch’s work is always in me, like a kind of libido. Inland Empire. Children’s films that deeply affected me as a child, and that I vividly remember seeing on the big screen, are certainly in there, at least in spirit. Watership Down. The Last Unicorn. Fantasia.

A huge influence that wasn’t cited was Kubrick’s 2001…the line “his life wrenched out of him like a discus/that goes flailing off to the Lord” was more or less directly inspired by the iconic bone-toss scene in that film. And the monolith scene at the end, in the marble mansion, with the sound of ancient man echoing through the hallways…right outside, like the tinkling distant sound of an orchestra would be audible throughout the halls of Gatsby’s mansion. That is beyond genius. It has never been equaled in film. Echoing because time has collapsed, and the dawn of humankind is now in the next room on the other side of the wall.

Then, the water imagery in the last scene of Gaspar Noe’s Irreversible—one of the most horrific and unwatchable of films, with the most beautiful ending–appeared, with its flashing space-time continuum, and the sprinkler system in that last shot that the children are gallivanting around fused with the Greek myth of Arethusa and Alpheus, united forevermore in the fountain. And of course, the sprinkler system is also the biblical fountain, the fountain of youth, the godhead.

Irreversible (2002)

JH: Much has transpired when we reach the opposing Pioneers, yet I consider each essential bridge poems. The first considers the 19th century practice of daguerreotyping a dead child. Following the action in the previous sections, this is the first moment in the book that considers death may be an insipid motionless activity after all. Everything moves in the room with the dead person except the dead person.

The second poem, however, maintains hope the mind of a shooting victim post-mortem is still very busy. I like how you give a little credence of the dead body, but ultimately have to ignore it. Do you feel society is too transfixed of physical aspects of being dead (and alive) and probably misses the exciting stuff?

LF: I think I’m too transfixed with it. As, of course society is and has been, down through the ages Memento Mori, “Everything moves with the dead person except the dead person." This is a brilliant question and a brilliantly worded question. I kept studying these Victorian daguerreotypes of people who had been photographed—right after they had died—with their eyes open. They had what Dickinson called “the distance/on the look of death,” but it’s a distance that has also evaporated in itself mid-flight because the soul has left faster than the eyes can process the recognition of its leaving.

You can see the same thing in some of Andres Serrano’s corpse photographs… an almost polite suspension in the eyes. There’s that soon-to-diminish flashbulb-brightness that’s always there, of course, but what we’re looking at is actually a stunned rapidity of departure. It’s not death that’s an insipid motionless activity, but the ‘politeness’ of the corpse itself, in its waiting for others to try to process it. I saw it as a taut bladder, like someone wanting to piss into salvation but holding it out of consideration for their loved ones/mourners, but after awhile they can’t hold it anymore, and their soul is starting to trickle out and piss itself. But they’re trembling, and their muscles are beginning to shake, and all sorts of things are starting to ‘fall’ out of their eyes… like the spider that appears, falling, gaping out of the eyes of the deceased, and falling out into the mourners, like all sorts of abominations and precious things, because the mind of the deceased is emptying into the beyond. The soul is being as courteous as it can for as long as it can, despite the fact that it is becoming more and more dazzled and seduced by the journey that’s now before it. But there is something gigantic starting to whoosh through the eyes, something massive, like a tsunami, and eventually that tsunami will flow out into pure light, into pure white water rapids.

The second Pioneers was inspired by an image on the Inland Empire deleted scenes disc (in fact, it was originally titled Inland Empire Deleted Scenes Disc, 16:36-11:06). The scene was a sequence of dulled, exploding lights that looked exactly like what someone who’d been shot in the back of the head while watching fireworks would have seen in their final moments. (And, interestingly, Lynch and the singer Moby do have a collaboration out called Shot in the Back of the Head, but it was post IE). The light slowed and imprinted, and it was as if part of American history itself had been shot, and was having a “life review” right up to the coast of the Atlantic, beyond which was England. The covered wagons had cycled back as far as they could go, and the holiday was flashing backwards into extinction.

JH: Mt. Fuji, Eden, Long Beach, Catalina, Tropic of Cancer, Scotland, Los Angeles, the Chesapeake Bay, Egypt, Sodom, Texas) are more memories than locations. There are also many instances where the speaker is making the most of bilocation. I’ll never forget when my old science teacher Mr. Jackson asked the PTA meeting “What if the human eyeballs are facing inward and we’re all looking at the backs of our own skulls?

Please feel free to grab a Little Debbie cake at the exit doors. Watching you all eat makes me hungry.” How might diatomhero comfort Mr. Jackson?

LF: Mr. Jackson was obviously a genius. He reminds me of Jake Tucker, that character on Family Guy with the upside-down face, saying to Meg: “maybe someday we can get married, and you can go up on me”. The bilocation is toss-up, actually. Obviously LA, the Rockies, the Chesapeake Bay—all places or features of places I’ve actually lived—are drawn from real life, though very little in the book can be said to be autobiographical, in the linear sense. Most of the places mentioned simply presented themselves.

JH: Robert Duncan occasionally included fun characters into his dramatic verse: First Beloved, Queen Under The Hill. You too bring stock characters to life in diatomhero. Could you provide some gossip on the following funky bunch: Peg Powler, Willa Harper’s children, Old Man Bickle, Madame DuBois, Mike Teavee? I’m especially fond of Old Man Bickle. His farm is mentioned during your rabbit reincarnation stage.

LF: I’ve discussed Peg, aka Jenny Greenteeth, and Willa Harper’s children (Night of the Hunter). Old Man Bickle just appeared, though I suppose I must have been thinking of Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle. I think Travis would have been quite at home in this book; he’s not as far from it as he might seem to be. Madame DuBois just appeared. I have no clue who she is.

And Mike Teavee, of course is the prodigal son of Wonkavision. In another poem (in the new book) there are souls that get churned up the blades of the Fizzy Lifting room, because, unlike Grandpa Joe and Charlie, they’ve not learned how to belch, or are unable to—the afterlife is full of hazards, after all.

JH: As a poet who plays with myth also, I’m consistently impressed by this work’s ability to incorporate myth without the reader needing to arrive at your text versed in that myth necessarily. In other words, you achieve equilibrium between the secular and the psychopomp. How did you check that balance while writing this?

LF: Thank you—that’s one of the greatest compliments I’ve received about the book. I’m glad it comes across that way, because I of course have no way of knowing how it’s coming across to anybody. I personally think that my poetry is wide open. There may be some relatively obscure references here and there and stuff, but I don’t think they really interrupt anything (I hope). What I really want is to create an images playground. Anyone can get something out of an image. Like being a kid at Disneyland, and riding Small World and being transfixed with wonder (rather than being consumed with wondering how the ride is mechanically engineered, like all those colorless and usually talentless academic critics with their obsession with “structure” are—as if an artist is incapable of writing a poem outside the “rules”; eg, the rigor of an institutional body brace and the breadth of geisha steps.

The first rule of Fight Club is “joyless”, they might say). However, this book is also a form of warfare, to me– against the time-space continuum trapping us, against mortality physically aging us against our own evolution and wisdom. diatomhero is critical thinking transmogrified into the imaginative. It is a book of strategy. Not, I repeat, escapism.

But back to the joy of images unto themselves. I loved what you said, awhile back, about Robert Desnos’s poetry feeling like the ball pit at Chuck-E-Cheese. That was such a marvelous observation, just beautiful, and a wonderful description of a triumphant legacy. We all know how terribly Desnos died. But he won, and his readers are still jumping into the ball pit.

JH: Will your second book of poems be similar or different from diatomhero? A bastard cousin perhaps? Where’s the next path of Pane di Altamura breadcrumbs for Lisa A. Flowers lead?

LF: I’m working on a surrealist study of early childhood now, and I’m loving it, and loving the process of trying to remember the way children (I) saw things before they were literalized or contrasted. I am also doing a series of reverse tone-poems, transcribing images from Schubert to Arvo Part to Krzysztof Penderecki. These range from the delightful “transcribing” Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite—I don’t mean its actual story, but the images it gave me—was wonderful, like revisiting my early childhood.

By contrast, transcribing Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima was obviously very dark. This transcription method was interesting because I would program in symphonies and just shift from, say, Pachelbel’s Canon into Penderecki, and the poetry would change instantly, be violently ripped out of itself into another image, with no warning. The poem would plunge sickeningly, like a heart monitor reflecting someone who had just had a massive and unexpected adrenaline dump. It was as if images from the Canon had been catapulted through the ceiling in a violent earthquake, and were lying dazed on the floor of the Penderecki apartment below, completely unaware of what had just happened. It also went the other way: going from Penderecki into the second movement of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto was like the train murder scene in Fire Walk With Me, when the angel suddenly appears to Ronette Pulaski and the screaming and the horror simply disappears into the holy silence of light, out of time.

There’s more synesthesia going on in this book, too. And, I suppose, more films throwing their images into other contexts, though I’m not going to keep repeating the same theme ad infinitum—my hope is simply to keep catching images worth keeping.

And I remain enchanted with something Werner Herzog said about the highest, most exalted points of the creative process, and its results: “There’s very rare moments where I get the feeling sometimes I’m like the little girl in the fairy tale who steps out into the night, in the stars, and she holds her apron open, and the stars are raining into her apron. Those moments I have seen and I have had. But they are very rare.”

_________________________________________________________________________

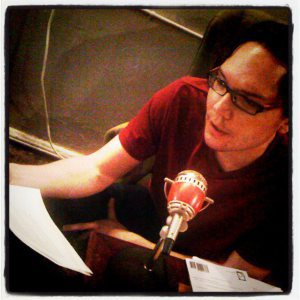

Jeffrey Hecker was born in 1977 in Norfolk, Virginia. He’s the author of Rumble Seat (San Francisco Bay Press, 2011) & the chapbooks Hornbook (Horse Less Press, 2012), Instructions for the Orgy (Sunnyoutside Press, 2013), & Before He Let Them Guide Sleigh (ShirtPocket Press, 2013). Recent work has appeared in Mascara Literary Review, Atticus Review, La Fovea, Zocalo Public Square, The Burning Bush 2, LEVELER, Spittoon, & similar:peaks. He holds a degree from Old Dominion University. He resides with his wife Robin.

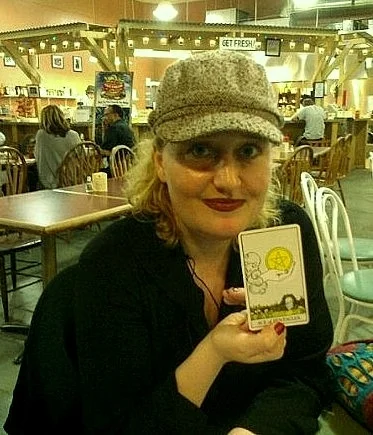

Lisa A. Flowers is a poet, critic, vocalist, cinephile, ailurophile, the founding editor of Vulgar Marsala Press, and the reviews editor for Tarpaulin Sky Press. Her poetry has appeared in various online and print journals. She is the author of diatomhero: religious poems.