BY MONIQUE QUINTANA, IN INTERVIEW WITH OCTAVIO QUINTANILLA

I first read Octavio Quintanilla’s poetry collection, If I Go Missing (Slough Press, 2014), on a late-night flight out of San Antonio, TX, where he has just completed his two-year tenure as Poet Laureate. Halfway through the book, the flight unexpectedly hit turbulence. I could see my friends sitting in other parts of the plane amongst strangers, all startled and subsided as the plane grew quiet with the soft glow from overhead lights. It seemed kismet that this happened while reading Quintanilla's book.

There is surreal and disconcerting energy in the poems and their transgressions. A cluster of grapes at a beloved’s mouth, the propensity of fleeing rabbits, and the slow ache of nostalgia are just a few notes that punctuate the book's range.

Terse, strange, and often tender, Quintanilla's newest work is expansive in the use of tech and multi-media images. For his project, FRONTEXTOS, started on January 1, 2018, Quintanilla publishes a visual poem on social media every day. Through the global fight against systemic racism and the uncertainties of the Covid-19 pandemic, Quintanilla creates in a non-linear fashion, responding to the politics of memory, language, love, and borders. He elaborates on these things with me, here.

Monique Quintana: In past interviews, you've shared that you consistently crossed the border with family throughout your childhood. That mapping of movement is in your first poetry collection If I Go Missing and in FROTEXTOS. Who were the storytellers in your family? How did their storytelling shape your paradigms about Frontera?

Octavio Quintanilla: Hard not to have storytellers in my family. We come from the Mexican ranchos where electricity came late. There were no TVs back then, the late 70s, so folks sat around to smoke cigarettes after supper, after a hard day's work in the fields, and talk. I grew up listening. More than writing, this is probably what I do best. The elders in my maternal family were storytellers, especially my grandfather, who I dedicate a poem to in If I Go Missing.

That’s how much I appreciated his words that, ultimately, fed my hunger to create. And about La Frontera, the stories I heard as a kid often made references to it, to the U.S., or “el otro la’o,” as it was colloquially referred to. Those first stories shaped my imagination of la Frontera, and I came to understand that to reach it, there was a journey to undertake, a river to cross, and creatures to bypass. If you made it, you might return home a hero with a handful of stories to tell around the fire.

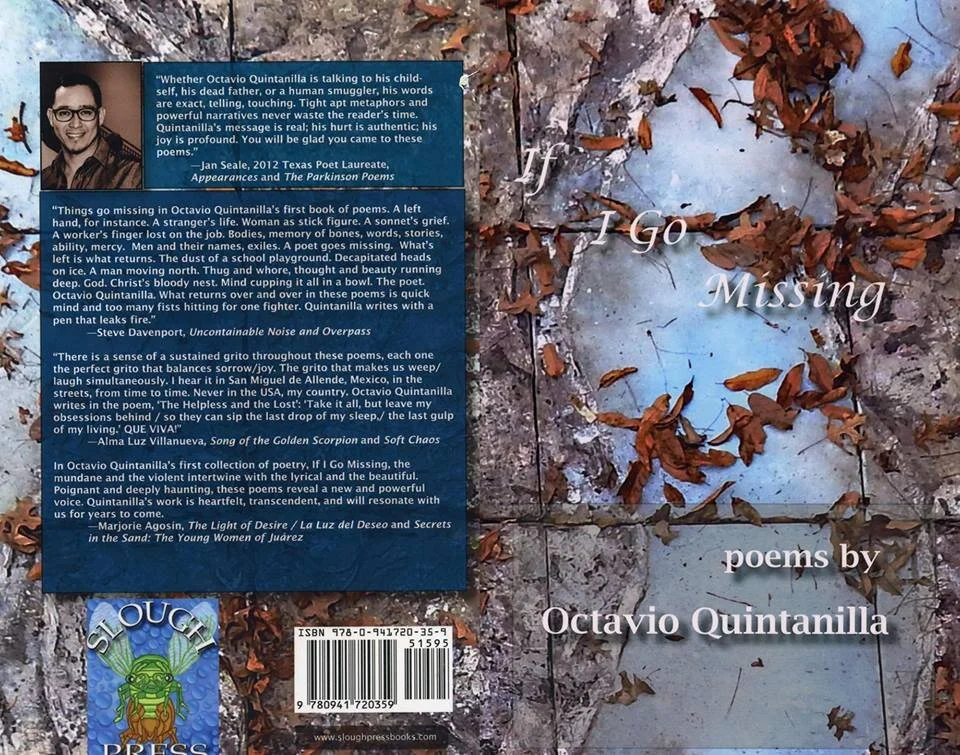

Cover wrap for If I Go Missing: Poems by Octavio Quintanilla (Slough Press, 2014)

Octavillo Quintanilla, Frontexto 93-20 [ from “Los días oscuros" series]

One of your FROTEXTOS reads, “Will you recognize my face / when I come looking for you, finally?”

Loss and absence is such a pervasive theme in FROTEXTOS. These themes especially resonate now. For some, there may be lost opportunities for reconciliation, making amends in strained relationships. How have these sentiments been complicated in your work, from the time you began the project in 2018? Also, what is a specific work of literature or art you feel explores these sentiments in a nuanced way?

These themes have always been consistent, even in my earlier work, but now I am finding new ways to evoke them in my Frontextos (the term frontexto is a blend of frontera and texto—border/text). Through text and image, I explore a personal and collective history of familial, geographic, and emotional dislocation associated with migration, immigration, and exile. I try to dig deep into the loss we often suffer when we move from one country to another, from one language to another, from one body to another.

And in a way, this sort of deep excavation complicates my relationship to craft, to the languages I speak and read, and to the blank page itself. Through the creative act, I acquire a sharper sense of what I am missing, which is often related to memory; and consequently, I also gain insight into what my absence means in others' existence. The complication of these themes goes hand-in-hand with my attempt to be as honest as possible about my relationship to loss—and my experience with it—because I want it to resonate with others as the work of Dermisache, Lispector, and García Lorca has resonated with me.

Octavio Quintanilla, Frontexto 78-20 [ from “Los días oscuros" series]

I imagine there might have been days where you felt less enthusiastic about creating a new piece for FRONTEXTOS. How did you push through that? Do you think FROTEXTOS has become a ritual for you? If you had a mantra for it, what would it be?

At first, it wasn’t too hard finishing one Frontexto per day. This was what I proposed to do. I was brimming with ideas. Then, as time went on, maybe after the first three months, it became harder. However, the more I stuck to the process, the more my senses opened up. I stopped taking things for granted. Everything became possibilities for poetry. It was exciting to wake up and not know exactly where the day was going to take me in terms of what I created for that day.

At first, the text filled the page, and then the image began to take over. The more I immersed myself in process, the more I felt I freed myself of the notions I had of what poetry should be, or could be. I think this is what it was—process as liberation. And maybe this is precisely why working on the Frontextos has become ritual, meditation, prayer. Action is the mantra.

Octavio Quintanilla, Frontexto 138-20 [ from “Los días oscuros" series]

Your writing and artwork seem to be in conversation with Latinx artistic traditions and others. I see you as an international writer/artist. What specific things can writers/artists do to create a global platform, especially if they aren’t able to travel abroad soon?

I often think about a writer’s/artist’s platform in terms of the local/regional, national/international. I always begin with the local, and then go on from there. Baby steps. And it's about networking, making friends, being open to opportunities, and sometimes doing work in which you are not always the center of attention. About being humble. About educating yourself in the work of writers who might not write in your language. It’s about receiving and giving back.

And it’s also about the work, the quality of the work. Social media helps quite a bit. It can keep you connected to writers and artists living in other countries. It’s an easy way to familiarize yourself with how others create and how your work might fit in. Sometimes it’s not even about having a platform, but about doing the work. If you are doing what you are supposed to, opportunities will come. Of course, what works for me might not work for someone else.

As Poet Laureate of San Antonio, TX, you’ve attended and organized numerous literary events. Due to Covid-19, communities are holding more digital literary events than ever before. If this is a learning moment for us, what do you think is gained from holding literary events online? How do you foresee new uses of tech impacting the trajectory of literary events?

I’m pretty sad that, for now, we can’t attend face-to-face readings. I was looking forward to seeing a few of my friends launch their new books. They adapted, of course, and did it virtually. This is where we are now. The virtual literary event, which is a thing I am getting used to. I mean, it's nice not to have to leave the house or fight traffic on your way to see a favorite writer. Nice not to have to dress up from the waist down to participate as a reader. So, there is an element of ease and accessibility. And maybe this might be one of the best things that will come out of this: literary events online that are more accessible to more people. That would definitely be a gain.

For now, however, I am definitely missing that great feeling you get to be around people waiting for a reading to begin—that electricity of bodies hanging around in one place, chatting, smiling faces. I don’t think the virtual literary event will disappear even when Covid-19 is no longer with us. And I don’t foresee it replacing the face-to-face reading, but I do hope it expands and diversifies our literary culture.

I’ve been asking this question of writers lately—If asked to create an entirely new piece to go in a time capsule, to be opened a century from now, what kind of story would you want it to tell?

It’ll probably be an autobiography. I think I would want this new work to tell about my journey to be here, at this moment, writing this answer to you.

Image via Octavio Quintanilla

Octavio Quintanilla is the author of the poetry collection, If I Go Missing (Slough Press, 2014), and served as the 2018-2020 Poet Laureate of San Antonio, TX. His poetry, fiction, translations, and photography have appeared, or are forthcoming, in journals such as Poetry Northwest, Salamander, Texas Highways, RHINO, The Rumpus, Alaska Quarterly Review, Pilgrimage, Green Mountains Review, Southwestern American Literature, The Texas Observer, Existere: A Journal of Art & Literature, and elsewhere. Visual poems have been exhibited in several galleries, including Presa House Gallery, Equinox Gallery, and at the Southwest School of Art in San Antonio, TX. He holds a PhD from the University of North Texas and teaches Literature and Creative Writing in the M.A./M.F.A. program at Our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio, Texas. Octavio’s new frontexto series, “Los días oscuros” (Dark Days) has been made possible by a grant from the Luminaria Artist Foundation.

Connect: [Instagram @writeroctavioquintanilla] Website: octavioquintanilla.com

Monique Quintana is a contributor at Luna Luna Magazine and her novella, Cenote City, was released from Clash Books in 2019. Her short works have been nominated for Best of the Net, Best Microfiction, and the Pushcart Prize. She has been awarded artist residencies to Yaddo, The Mineral School, and Sundress Academy of the Arts. She has also received fellowships to the Community of Writers, the Open Mouth Poetry Retreat, and she was the inaugural winner of Amplify’s Megaphone Fellowship for a Writer of Color. You can find her @quintanagothic and moniquequintana.com.

![Octavillo Quintanilla, Frontexto 93-20 [ from “Los días oscuros" series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5622fb11e4b0bca6fa5c1525/1593407208635-8FWW3GUB48RNPSKIWD9L/Quintanilla%2C+Frontexto+93-20+.jpg)

![Octavio Quintanilla, Frontexto 78-20 [ from “Los días oscuros" series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5622fb11e4b0bca6fa5c1525/1593404938752-8DO3EDF2RM06XWCV5M4O/Quintanilla%2C+78-20+.jpg)

![Octavio Quintanilla, Frontexto 138-20 [ from “Los días oscuros" series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5622fb11e4b0bca6fa5c1525/1593405117451-78D5NPG2WNHJMLC5AM6L/Quintanilla%2C+Frontexto+138-20+.jpg)