Laura Linart is a poet and writer based in New York City. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in publications such as Green Mountains Review, The Rumpus, Pembroke Magazine and 580Splits. Say hi to her on Twitter or IG @Pennyscientist

Read MoreEvery Body Has Ghosts by Cate McGowan

BY CATE MCGOWAN

Every Body Has Ghosts

Below a yellowed tree,

weeds fringe the driveway’s

borders. Anoles pump.

They jut, and the bigger

lizards skitter along

the yard’s edge. While

daylight’s needles stitch

threads up the spathodea,

seven DeKay’s snakes slue

like scarves through

the new ivy. Though

it’s already five o’clock,

I haven’t heard from you

yet. Not this week.

Not this month. You’re

gone without a word.

So far, only green silence.

Someone next door opens

a second floor window,

and a toddler shrieks

and shatters the stillness.

The child’s cry skylarks

the mimosa, shrinks,

then dissipates through

the evening’s haze. I shake

out our wet clothes.

In the breeze, the clothesline

snaps my red blouse

as it dances, my empty sleeves

waving in the wind to no one.

Cate McGowan is a fiction writer, essayist, and poet. Her work appears or is forthcoming in Norton's Flash Fiction International, Glimmer Train, Crab Orchard Review, Tahoma Literary Review, Crab Fat Magazine, Ellipsis Zine, Barrelhouse, Shenandoah, Into the Void, Louisville Review, Atticus Review, Vestal Review, Unbroken, and elsewhere. A native Georgian, McGowan's an Assistant Fiction Editor for Pithead Chapel and is pursuing her Ph.D. She won the 2014 Moon City Short Fiction Award for her debut short story collection, True Places Never Are, published in 2015, and her debut novel, These Lowly Objects, is forthcoming from Gold Wake Press.

A Guide For Witches and Writers: "The Magical Writing Grimoire"

What Is The Magical Writing Grimoire? Is it for witches or writers — or both?

The Magical Writing Grimoire is a book of inclusive and accessible rituals and writing prompts for anyone who feels called to using words as a source of healing, empowerment, joy, generativity, and self-exploration. It is designed to integrate ritualistic living and to incorporate sacredness into our lives in meaningful and easy ways.

It’s for witches and non-witches (including people with secular beliefs, like myself), although of course it’s heavily based off the archetype of the witch: The witch, to me, is strong, rebellious, empowered, empathic, and bold as fuck. The witch is also conscious — of the self and others and the earth. So, it works heavily with archetypes and symbols, but it invites people who have specific beliefs to incorporate their beliefs into the work.

Really, the book is about tapping into and using your own power, your own voice, your own ideas.

It’s for writers and non-writers — anyone who is interested in the sacred, beautiful power of poetry or journaling or letter-writing, or timing writing practices to nature’s ebb and flow.

It also focuses heavily on shadow work — or unearthing the silenced, dark, shadowy parts of the self.

What will readers find within its pages?

Lots of rituals, lots of writing prompts, meditations, quotes from the most inspirational and wonderful people and writers, poems I wrote myself, glimpses into my personal life, and so much more. Plus, it’s really beautifully illustrated.

What is the inspiration behind The Magical Writing Grimoire?

The book was gestating in my mind for several years, but I didn’t know what its shape until the past year or so; I knew I wanted to write a writing guide — one that balanced the ritualistic with the pragmatic and every day, one that used writing as a form of magic. More than using the occult in order to generate writing, it’s about using writing to make your life more magical.

It starts with the word and ends with the word.

It’s deeply rooted in recovering from pain and trauma. When I was younger, the number one thing that got me through times of extreme trauma (family separation, foster care, CPTSD, financial instability, chronic illness) was writing. Writing gave me my voice back. It was a tool for reclamation. But more so, it was a tool for joy, creativity, and empowerment.

The ability to write is a privilege for many of us, but it’s also a free tool that can help save us. I’ve seen writing help women in domestic shelters, college students move through self-esteem issues, and incarcerated individuals tell their story. It is something sacred in itself because with our words we are taking nothing and making it into something.

So I wanted to design a gentle but effective book that people — especially any marginalized community — could use to tap into their truth and self, in a way that felt right for them. It’s guided, but it allows space for reinterpretation and individuality so that anyone can tap in.

Is it similar to Light Magic for Dark Times?

It is, and it’s not. Like Light Magic for Dark Times, it is grounded in accessibility and inclusivity. It also offers different (but looser) chapter focuses, like manifestation, mindfulness, healing, conjuring your voice, creating a grimoire, and more.

Unlike Light Magic for Dark Times, it provides a much deeper dive in terms of the rituals and the writing prompts, and it’s filled with poetry and quotes to meditate on. It’s also much more about the process of long-term self-exploration (and excavation!) than about quick, one-off rituals for different purposes. I think the two actually pair super well together!

What are your beliefs?

I’m secular (for lack of a better, more nuanced word), so I don’t work with or believe in gods, goddesses, angles or other deities. However, I work closely with the natural world (especially the power and energy of water), shadow work, energy, archetypes, and symbols. For example, I see the elements as powerful tools, offering lessons and glimpses of the purity of aliveness — and I see the astrological signs as symbols of the human condition.

When does the book come out?

It’s born on April 21, so it’s a Taurus! But let’s be honest — it was finalized and sent to the printer during Scorpio season. It’s very much a Scorpio book — it’s dark, intense, powerful, and transformative. But, like a Taurus, it wants to find beauty, comfort, and artistry. And because it comes out in the Spring, it’s a great way to kick off the new year with energy, creation, and rebirth.

People are already saying some really kind things about it, and it’s included in a few Most Anticipated lists, like in Cunning Folk and over at Patheos by Mat Auryn.

PREORDER THE MAGICAL WRITING GRIMOIRE NOW!

If you do, send preorder proof of purchase to magicalwriting@quarto.com and you’ll receive downloadable prompts and magical poetry to power up your magic.

PS: Follow the book’s journey on Instagram at @Ritual_Poetica.

Photo: Joanna C. Valente

Collaborative Poetry by Joanna C. Valente & Stephanie Valente

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body), #Survivor, (forthcoming, The Operating System), and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

Stephanie Valente lives in Brooklyn, New York, and works as an editor. One day, she would like to be a silent film star. She is the author of Hotel Ghost (Bottlecap Press, 2015) and Waiting for the End of the World (Bottlecap Press, 2017). Her work has appeared in dotdotdash, Nano Fiction, LIES/ISLE, and Uphook Press. She can be found at her website.

Poetry by Nadia Gerassimenko

Nadia Gerassimenko is the founding editor of Moonchild Magazine and proofreader at Red Raven Book Design. She is a freelancer in editorial services by trade, a poet and writer by choice, a moonchild and nightdreamer by spirit. Nadia self-published her first chapbook Moonchild Dreams (2015). at the water’s edge is her second chapbook (Rhythm & Bones Press, 2019). Follow Nadia on Twitter.

3 Poetry Books You Should Be Reading

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body) , and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

Poetry by Jeannine M. Pitas

BY JEANNINE M. PITAS

June 24

Feast of St. John the Baptist

Today my head has been removed,

traded for a jug of wine, a pluck

of the lyre, a young girl's careless

dance. In Orthodox icons I hold

myself on a platter; faithful ones

bend forward to kiss. I never knew

this was the price of living

on locusts and wild honey, for preparing

my cousin the carpenter's way. Today the light

begins its slow death; I know

I will rise again. In two thousand years, a girl

who bears my name will dance

around a bonfire, surrounded by old men and women,

tiniest children, dancers on stilts, young

girls in white dresses with ivy crowns.

She will whirl and whirl, dizzyingly dance,

exalting in her own beauty.

The price will be her head.

A man she thought she loved

will smash her into a wall

and her head will fall off.

She will pick it up, carry it in

a backpack or purse while a replacement

is painted over the space. Years later, again

on my day, she will sit on a bench on Aliki Peninsula

beside the marble ruins of a basilica

made in my cousin's name.

She will look at the columns and archways, watch

summer's highest, brightest light fall

on the olive trees. I will come to her,

take her hand. When I wipe away

the painted face, she will open

her purse and hold out to me

the torn head she still holds. My cousin

will come to help me. We will lift it,

place it on her shoulders, suture that wound

as all the scarved women

lighting candles before Orthodox icons

have done for me. We will help her

to her feet, beckon her to join us

in our search for others

who've lost their heads.

Wings of Desire

An angel whispers to readers in the library.

He's tired of everyone wanting something different.

A trapeze artist dressed like an angel

doesn't know that real angels are wingless.

I wait for my photo at the machine

and emerge with another face.

This is the world of one-shoed walkers

who shade themselves with borrowed umbrellas,

sign their names with dropped pens,

open doors with lost keys.

Stones come alive. Time can't heal.

No, time's the illness.

The first strands of grey hair. An old photo album.

The lost storyteller, lost peace.

The blue ocean, sky. Afternoon coffees.

Cuban cigars. Dragons. The bed.

The world that shrinks to the size of a room.

The choir of young women who come to sing.

The grass tall enough to hide

or make love in.

The deep river you didn't find hard to cross

because your beloved was waiting on the other side.

An immortal singer turned organ grinder,

ignored or mocked.

Abandoned railroad tracks. The other side.

The crucifix hanging from the classroom wall.

The plaid uniform your grandmother starched.

The borders. The country with as many states

as there are citizens. Rags pledged to each morning,

folded each afternoon. Shibboleths.

Barbed wire. Private security guards.

The world in color. Sunsets, lonely rooms.

Cherry cough drops. A nurse's kind face.

Your bed. The lamp turned off.

Panic

I met Pan when I was 21. It's said he, god of shepherds, can be found in mountain fields, but I encountered him on my college campus, in a hidden quad behind a stone building with icicles dangling from the roof, tiny daggers. It was winter. He came alone. He struck me with his staff and gave me altitude; my insides crumpled like autumn's last falling leaf, shriveled as a sheet of ice hit my shoulder. I lay there. The snow shone gold; the treetops blazed, but no voice emerged from within them, no all-important “I am.” Just the opposite: “I am not.” This is not me. I shook and saw a strange aura around myself, a halo of gold and green. Rats and mice nipped my toes; the ground opened to reveal sharp rocks waiting to tear me into sinews and blood. Beneath them a blue sea waited to caress me and not let me go, beauty and terror both much too close. At last he turned away. It took a few minutes to trust he wouldn't be back. The mountain flattened; the blazing trees regained their green. In the distance I heard the bells of sheep, their gentle bleating. A blue sky entered my insides. I stood; I could feel the halo still around me. I could still smell the aroma of meadows after winter's melting, of soft trilliums drinking the sun between the branches of skeletal trees; I could taste the first mint leaves. Lush pastures rolled through my stomach; my heart broke into cumulus clouds; pink mimosa flowers sprung from my hands. My lungs were filled with the blueness of early spring.

Jeannine M. Pitas is a poet, teacher, and Spanish-English literary translator. Originally from Buffalo, New York, she has called many places home: Montevideo, Krakow, Managua, Toronto, and most recently Dubuque, Iowa, where she has resided since 2015. She is the author of three poetry chapbooks: Our Lady of the Snow Angels (2012) and A Place to Go (2015), both published by Lyricalmyrical Press in Toronto, and thank you for dreaming (2018), published by Lummox Press in 2018. Her translation for four books by acclaimed Uruguayan poet Marosa di Giorgio was published as I Remember Nightfall by Ugly Duckling Presse and shortlisted for the 2018 National Translation Award. Her first full-length collection of poetry, Things Seen and Unseen, is forthcoming from Oakville, Ontario-based Mosaic Press. She teaches literature, writing, and Spanish at the University of Dubuque.

Poetry by Danielle Rose

BY DANIELLE ROSE

Variations on Drawing Down the Moon

it is about drawing things in. i want

to be tree-roots / & lightning

striking an open field.

how first i open myself like the face

of the moon / so that i become

the face of the moon.

& into me flows the face of the moon.

goddess / descend into me

through me into the earth.

it is about remaining open like how

i want to be tree-roots / to hold

you both hopeful & ashamed

that i may be unfaithful / i imagine

that i am tree leaves & they

drink in the moonlight

& into me flows the hungry moon.

goddess / projection / demon

whatever just enter me now.

this is how you drink

divinity / & perhaps why

tides swell. in both there is dancing.

arms toward the sky / you drink god

then she seeps out again.

this must be how

we can bear to be so empty / so

we can be so full / so we can be tree-root

drawing ourselves into the moon.

On Dancing

these are the skills i never quite understood / the idea of celebration

like a trip to the dentist / i understand how out of place i am

awkward everything elbows & shoulders / awful at blowing out candles

& my wishes were just beads of sweat a sudden dampness

a stumble / because this was how i was taught to dance

to step on others’ toes / but i am not awaiting extradition

i am learning how to belong to where i am / because this is the way a sewing needle

becomes a sword / & how i stitch together myself a dance

Danielle Rose lives in Massachusetts with her partner and their two cats. She is the managing editor of Dovecote Magazine and used to be a boy.

Review of Anna Suarez's 'Papi Doesn't Love Me No More'

While the bruise of men is present in these poems, there are great alliances with women, “Sister says I touch/ and I destroy. ” The aspect of doubling is in this poetry, but women aren’t harmed by their doubles, rather, they feed of each other’s prowess. The twinning of the speaker’s self adds to the labyrinthine structure of the book, so though you encounter a new scene is each hole and crevice, there is still that familiar ache of letting go and the hope of regeneration.

Read More3 Poems You Need to Read This Month

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body) (forthcoming, Madhouse Press, 2019), and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

Poetry by Denise Jarrott

BY DENISE JARROTT

Denise Jarrott is the author of a collection of poems called NYMPH (vegetarian alcoholic press) and a chapbook, Nine Elegies (dancing girl press). Her work has appeared in Black Warrior Review, Bombay Gin, The Volta, Poor Claudia, and elsewhere. She was nominated for a 2018 Pushcart Prize and is currently at work on a series of essays in conversation with Roland Barthes' A Lover's Discourse. She lives in Brooklyn.

Photo: Joanna C. Valente

Poetry by Joanna C. Valente

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body) (forthcoming, Madhouse Press, 2019), and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

Trevor Ketner

Trevor Ketner Is Creating a New Poetry Press & It's Gonna Be Real Lit

Books are a joy and gift. They teach us who we are, what we are capable of, and give us valuable lessons to remember. More importantly, however, they teach us and give us insight about the lives of others. Editors, in many ways, are the facilitators of these books, different portals into another world - and are the unsung heroes of books.

Read MoreChristine Shan Shan Hou In Conversation With Vi Khi Nao

BY VI KHI NAO

in conversation with CHRISTINE SHAN SHAN HOU

VI KHI NAO: How would you describe your poetry and your art (collage)? Do they seem similar to you? How close do you feel to Dadaism? Is there a particular literary movement or artistic movement you wish had been invented?

CHRISTINE SHAN SHAN HOU: I look at both my poems and my collages like miniature worlds—each filled with their own characters, tastes, textures, and elements of strangeness and love. However, I actually feel like my poetry and collage are quite different from one another; my poetry—specifically the process of writing poetry—feels heavier, darker, whereas my collages feel lighter and more directly pleasurable. Writing poetry is hard. Collaging is fun. I don’t feel particularly close to Dadaism. I remember studying them in college and being very excited at first, but now I look at them and think: Look at all those old white men! Now that we’ve seen the first image of the black hole, I wonder: What would movement look like in a black hole?

VKN: Your collection, Community Garden For Lonely Girls, shows that you have a natural linguistic impulse to produce words/thoughts that mirror each other—as if you were trying to use the rhetoric of repetition to create content by allowing it to erase itself through doubling. For example, lines such as “my ancestors’ ghosts have ghosts” (p.3), “my split ends have split ends” (p. 4), “If I lay here, how long will I lay here?” (p. 18), “Act without acting out” (p.54), etc. Do you prefer sentences/lines that never look at each other or always look at each other?

When you write these lines, I think that your poetry uses symmetry as a way to acknowledge the lexical self they haven’t been able to access; when a particular word repeats itself in the same context, it brings something out. What do you hope to bring out? In each other, meaning poetry and yourself.

CSSH: I love this question, this image, of two sentences/lines looking at each other. It brings to mind an artwork by the Korean artist, Koo Jeong A. She made this one piece called Ousss Sister (2010) where two projections of the full moon are facing each other within a very narrow space. It is so bewildering, this concept of a self without eyes looking at one’s self. Is this still considered “looking” if one can’t see? Does one have to have eyes in order to have a face? I prefer sentences that look at each other, even though my sentences don’t always have eyes. Meaning arises from the act of looking. Repetition ensures its existence. Where there is existence, there is possibility bubbling beneath the surface. When I repeat words within sentence structures I am suggesting a possibility. A possibility for what? I don’t know.

When people read my poetry their hair grows a little longer.

VKN: That is a mesmerizing image from Koo Jeong A. It reminds me of a pair of lungs. If your collages and your poems were to arm-wrestle each other and the yoga instructor/practitioner in you was forced to be the ultimate referee, who would win that tournament? And, ideally, which two aesthetic competitors would you like to see compete with each other in a match? Would you prefer to be the cheerleader or the umpire? If the winner between the two mentioned competitors (collages & poems) is the one who is able to break a reader/viewer’s aesthetic heart the fastest, which one would it be?

CSSH: My collages would definitely win! My visual art feels lighter and not so bogged down by my past, by my thoughts, or by the heaviness of the language in the air! When I make collages, I am often listening to a podcast, or music, or have a tv show on in the background, all of which feels good for my brain, whereas when I am writing poetry, I can’t have any other distractions. I have to be very in it. One could argue that this extreme awareness of the present when writing poetry seems more mindful than the multitasking of collaging, but ultimately for me, the collage process is much more enjoyable, and the yoga instructor in me will lean towards the direction of joy. I think my collages would break the reader/viewer’s aesthetic heart the fastest.

I would love to see film go head-to-head with any form of live art.

VKN: Why do you want your readers’ hair to grow a little longer? I would hope it would grow shorter, to defy the law of gravity or the law of expansion.

CSSH: Honestly, I don’t know why! It was just an image that floated into my head. I think it’s because I equate growing hair to growing older, which also means growing calmer.

VKN: You are currently a poetry professor at Columbia. Do you enjoy teaching? Would you ever play a prank on your students? If so, what would be one prank that would bring out your impishness? What collage of yours or poem of yours would be a great example of a prank? What poem or collage of yours (or someone else’s) would be equivalent to this prank? And, what is the best way for a student of the arts or in general to express rebellion?

CSSH: I do enjoy teaching. It is very invigorating to be in a room with young people who are as excited by poetry as me! However, to be honest, I prefer teaching yoga over teaching poetry. I’m not much of a prankster, but the poem that is closest to a prank is “Masculinity and the Imperative to Prove it” in Community Garden For Lonely Girls

That prank is very funny, but also mean. I think I’m too sensitive for pranks. I realize that makes me sound a little bit like a wet blanket, but I am ok with that. I think the best way for a student of the arts to express rebellion is to pursue the practice outside of the academic institution and at one’s own pace, whether that pace is a sprint or a crawl.

VKN: I view pranks as one way or a tool an artist can use to express him or herself creatively in a comedic fashion. My brother sent me that prank at a sad point in my life, and it cheered me up and made me feel closer to him. I do not view it as a gesture of meanness, as in: shampoo is just shampoo and irritation is irritation and water running down one’s face excessively once every millennium is a divine act of profound charity.

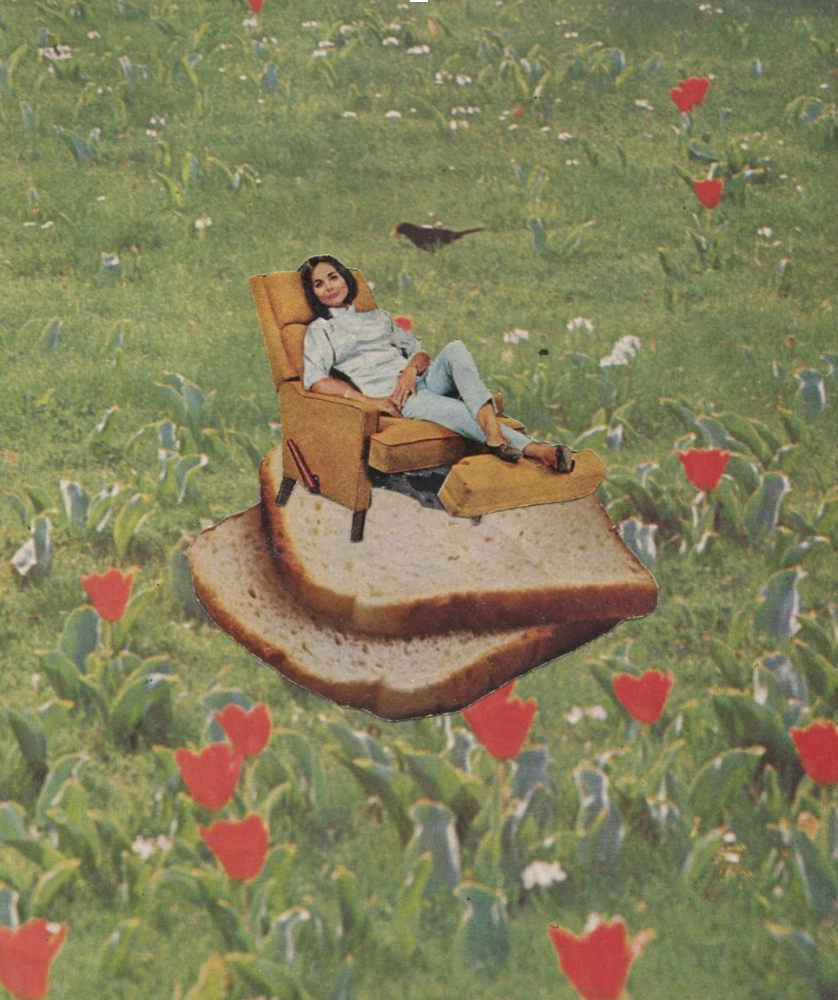

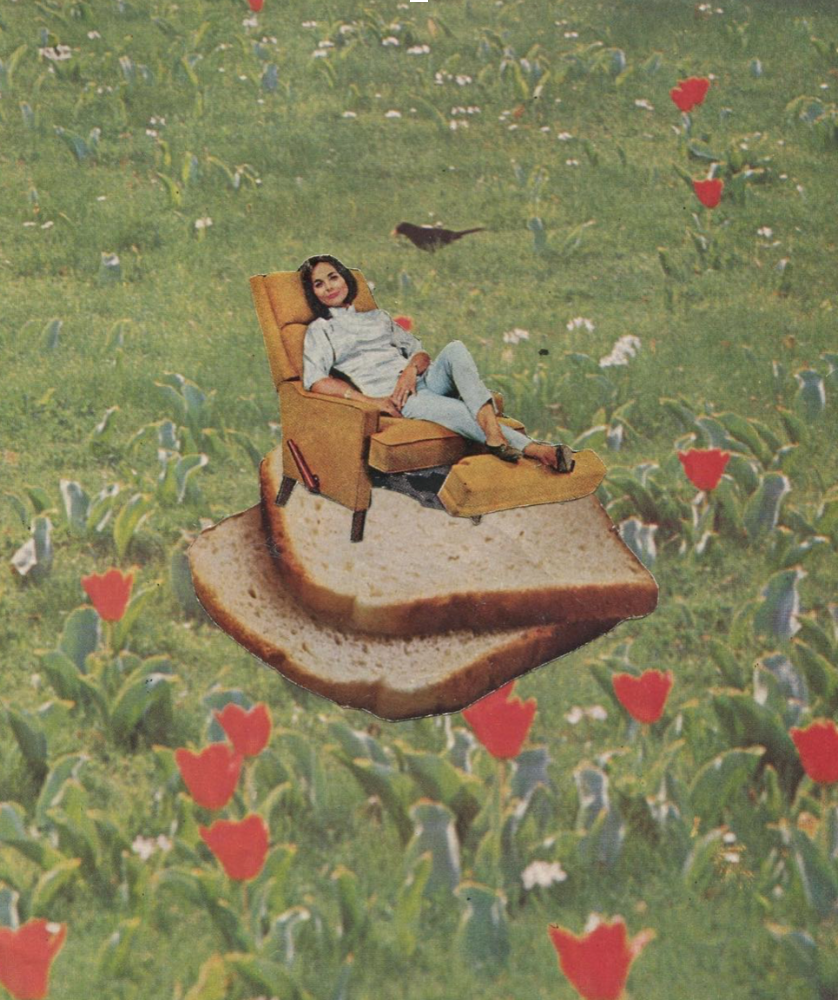

Speaking of visual or kinetic creativity, one can view your visual works on your Instagram: hypothetical arrangement. Can you talk about the piece below? Can you walk us through the process of how you created it? From seed of conception to final product?

How often do you make your collages? I know you have one daughter, but in terms of sibling rivalry (how many of you are there, btw?), has poetry ever fought with you for creative space because you devote more time to one discipline or art form rather than another? You must understand scissors and surgical knives very well. Do you ever feel like you are a surgeon? Have you ever created a collage where you feel like you are performing a heart surgery and the life of this art piece heavily depends on how well you incise? Have you ever cut through the artery of an image and felt lost or lonely or regretful or sorrowful or overjoyed?

CSSH: This collage is called “Self-actualization (in recline).” When I make collages I go through old magazines and start cutting out images that speak to me. I have several categories for images and three of them are: food, women, and seascape/landscape. I don’t remember how I arrived at this final image, but I remember liking the way the red flowers contrasted with the dreary, soft slices of bread and then the ease of the woman’s posture. I like her shimmering periwinkle outfit and her pet bird in the background.

I try to make at least one collage a week, but that doesn’t always happen. I tend to make many collages in a short period of time, or even in one sitting, and then occasionally mess with them for a few minutes every few days, until I feel satisfied with them.

I am one out of four siblings. However I do not see any “sibling rivalry” between poetry and my yoga and/or collage practice. I think they all work in harmony with one another and give each other the time and space to breathe.

Yes! I definitely feel like a surgeon when I am making collages. I use an x-acto knife so I can really get into the details. And there are so many pieces I’ve considered “ruined” or “dead” because I was too impatient with the cutting of a very precise detail. But then I immediately let it go. I try not to get too precious about paper arteries.

VKN: Will you break down the poem “A History of Detainment” (p. 72) or (“Masculinity and the Imperative to Prove it,” or why this poem may feel pranky to you) from your collection, Community Garden For Lonely Girls, for us, Christine? Can you talk about the process of writing that poem? Do you recall writing it? What was it like? Where were you emotionally? Intellectually? Were you preparing a meal? On a train? Or what piece of writing/art inspired it? Did it take you long? And, could you talk to us about this line: “While navigating the meadow of hypotheticals, I tripped and broke my arm” (p.72). If you broke your arm, what one line from a canonized poet would you want to scribble on your cast?

CSSH: “A History of Detainment” is so long and heavy and my brain is so tired after a full day of running around with my kid. But I can say a little bit about “Masculinity and the Imperative to Prove It”: When I was a child, my grandparents owned a Chinese restaurant called Oriental Court inside of a New Jersey shopping mall. Every Saturday night my entire paternal family—grandparents, all of their children and all of their children's children—would eat dinner after the mall's closing hours. After the meal, me, my siblings, and my cousins would run around like crazed little people in the empty mall and play all sorts of games including: "Red Light Green Light," "Red Rover," "What Time is it Mr. Fox?" and "Mother May I."

However, the golden rule was that we had to wait at least thirty minutes after eating before engaging in any physical activity, or you would get sick. When I was a young girl, I was often ashamed of my body. I used to wish that I were white so that I could fit in with the popular crowd; I would make myself throw up because I thought I was fat; and because I was sick a lot as a child, I would view my medical issues as a reflection of moral shortcomings. In other words, I was a very sad child. But at the end of the poem, the sad child is actually a fish. And we all know that a salad can be both a curse and a blessing.

VKN: That’s a very beautiful story, Christine. I understand your tiredness. Perhaps this last question then: What do you think is the best way for one poet to feel at home in a poetry collection by another poet?

CSSH: Poetry collections are like homes unto themselves. I think the best way for a poet to feel at home in someone else’s poetry collection is by taking their time while reading it and listening closely, attentively, to what it is trying to say.

Christine Shan Shan Hou is a poet and visual artist based in Brooklyn, NY. Publications include Community Garden for Lonely Girls (Gramma Poetry 2017),“I'm Sunlight” (The Song Cave 2016), and C O N C R E T E S O U N D (2011) a collaborative artists’ book with Audra Wolowiec. She currently teaches yoga in Brooklyn and poetry at Columbia University. christinehou.com

VI KHI NAO is the author of Sheep Machine (Black Sun Lit, 2018) and Umbilical Hospital (Press 1913, 2017), and of the short stories collection, A Brief Alphabet of Torture, which won FC2’s Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize in 2016, the novel, Fish in Exile (Coffee House Press, 2016), and the poetry collection, The Old Philosopher, which won the Nightboat Books Prize for Poetry in 2014. Her work includes poetry, fiction, film and cross-genre collaboration. Her stories, poems, and drawings have appeared in NOON, Ploughshares, Black Warrior Review and BOMB, among others. She holds an MFA in fiction from Brown University.

Poetry Weekly: Yesenia Montilla, Martín Espada, Denise Jarrott

As the senior managing editor at Luna Luna and the founding editor at Yes Poetry, you could say writing is important to me, especially poetry. For me, it’s vital to highlight poetic voices in order to support literature, activism, and expression.

Here are three of my favorite poems I read recently.

Read More