I don’t know your name, little girl, but I do know that I owe you an apology. I would have given you one in person, but I was feeling too ashamed. Do you know this word, shame? I hope you don’t. I hope you never do.

Read MoreFlickr

I’m Not Your Inspiration Porn: On Being a Disabled, Queer Survivor

I'm a queer, disabled survivor, but I'm not your "inspiration porn."

BY ALAINA LEARY

I remember the first time I heard it: “You should be so proud, after all that you’ve been through!” I was 11 years old. It was within a year of my mom’s sudden, unexpected death, and I’d been given several awards and switched into the Honors programs halfway through sixth grade.

When I first heard it, there were so many thoughts running through my head. I was only a kid, and I really didn’t know how to react to compliments yet. I heard that I should be proud of my accomplishments, but I also heard that pride was based on the struggles I’d survived. Would I have been showered with these accolades if I were just a normal 11-year-old?

I guess I’ll never know. Since day one, I’ve been part of the other—marginalized groups that are frequently discriminated against. I have several interconnected sensory and developmental disabilities—autism, with comorbid dyspraxia and sensory processing disorder—that can be hard to explain to other people. I have no sense of balance, so I can’t ride a bike, walk in a straight line one foot at a time, or walk the balance beam. My brain shuts down if I experience sensory overload, and it’s very difficult for me to learn faces, geographical directions, and, for whatever reason, the parts of a sentence.

Because I’m disabled, from the beginning, I was always going to be subject to inspiration porn—either that or its direct counterpart, people feeling sorry for me or my caregivers because of the things I can’t do.

But I never made it to the point where I was somebody’s disability-specific inspiration porn, because my story became so much more than that. My story became one of survival, perseverance, and following your dreams. And people loved it.

When I was 11, my mom died unexpectedly, and my world was thrown into chaos. At the same time, I was exploring my sexuality, and came out as gay to friends and family. I was bullied relentlessly by my peers for years as a result. In early high school, I was the victim of sexual assault three times. In college, one of my best friends died in a car accident, and I was raped at a college party. Along the way, I’ve also lost aunts, uncles, grandparents, family pets, and have dealt with my dad’s worsening physical and cognitive health.

“Inspiration porn” was a word coined by the disabled community, and it’s a word that I sometimes use to describe myself. The people who are tokenizing me don’t always know that I’m disabled, but they might, or they see the symptoms but don’t recognize that they make up a disability. I've taken the word to mean, in my personal experience, that people use my story to be inspired because of what I've accomplished in spite of hardship. In spite of disability, in spite of being marginalized, in spite of so much loss at a young age.

Being inspiration porn does a funny thing to your psyche: in equal parts, you’re so proud to be such an advocate for the communities you’re a part of, and you’re happy to inspire others who may be struggling; but you’re also thrown off, because you’re so much more than an “inspiration because of your circumstances.”

When I first started receiving these compliments, I was only a kid. After years of one-on-one tutoring, special education classes, and physical, speech, and occupational therapy, I made the Honor roll. I got into Honors classes. I got the top awards for best grades in English and Science. I read more books in a year than anyone in my class. I was on TV. I was in the newspaper. I wrote a book, met the mayor of my town, and got an award for it.

And what did people see? They saw the story. They saw me as a headline. Here I was, seemingly “formerly disabled” girl who failed English class, who barely passed the second grade, who couldn’t ride a bike or walk up the stairs one foot at a time, getting straight A’s.

Somewhere along the way, being everyone’s inspiration porn became a part of my identity. I heard it so often that I went along with it—and that was easy. All I had to do was keep up a string of constant accomplishments, each one slightly more impressive than the last, and make sure they were publicly known. In more ways than one, I became almost addicted to the rush that came with the slew of compliments.

But giving in to the inspiration porn doesn’t allow me to fully be myself. I am disabled. I am queer. I am a rape survivor. But there is so much more to those parts of me than my ability to accomplish “in spite of.”

I am disabled. I am queer. I am a rape survivor. But there is so much more to those parts of me than my ability to accomplish “in spite of.”

People mean well, and they sometimes get it right. My cousin and I have a special relationship, in that the first thing she always says to me when we hang out is, "I'm really proud of you. But I would be proud of you no matter what." She congratulates me on my work and my education, but says that her love and pride are not contingent on those markers of success. They're unconditional.

It's something we don't talk about often. Not in the space of marginalized groups, but not in majority spaces either: the radical idea that you can be proud of someone and love them beyond the way they're meeting societal standards of success, like education, work, and professional achievements.

It's probably why I'm so bad at taking compliments. Just last week, I was distinguished as an alumni speaker at my alma mater, and it involved being showered with compliments both before and after my speech from faculty and students alike. Part of it is because I've adopted a lifelong growth mindset; the idea that my work and I can always be improved. But part of it is also because, in the back of my mind, I'm wondering: "Would people be proud of me if I were a queer, disabled survivor who wasn't published in Cosmopolitan, earning a master's degree, and working full-time?"

That's not because the people in my life make me feel that way. It's because I've internalized the idea that being disabled and a survivor are bad, and they're things to overcome and leave behind. It's only in recent years that I stopped feeling the same way about being queer, and a lot of that has to do with shifting the way we talk about LGBTQIA people: not solely classified as burdens or inspiration, but as fully-actualized people. I'm starting to see the same mindset shift with disability and mental health, but there's so much work to be done and conversations that need to happen in a public space. A huge step is adding well-rounded representation in the media, so people have a window to look through; to see that a disabled person or a survivor is so much more than just a label.

Being a disabled, queer survivor isn’t something I overcame to succeed. Part of the reason I’m doing so well—living my life, loving it every day—is because I’m disabled. I may not be able to diagram a sentence, but I can spot copyediting mistakes just because they don’t fit the patterns I’ve seen across hundreds of thousands of words I’ve read. Because of my disability, I have the intense ability to hyper-focus on something I’m doing for several hours at a time without interruption. I’m also very adept at picking up new tasks and creating, and it’s because of my disability that I was able to teach myself Photoshop, InDesign, HTML/CSS, and JavaScript.

After my mom died, I threw myself into being busy. I’d always been a creator—someone who wanted to make the things that didn’t already exist, and who was very hands on in her approach to creating. Being busy distracted me from being sad. During the nights when I was home after school and mourning, I threw myself into writing a book about losing my mom, and then producing it: creating the layout, setting the typography, designing the cover, and printing and binding it.

Being busy provided reassurance for me when I went through tough times. I lost my mom, so I learned how to code web layouts and design graphics for them. I was sexually assaulted, so I threw myself into photo editing and professional photography. I was bullied for being queer, so I moderated online social spaces for LGBTQIA youth. These were all skills I continued developing, and I owe a lot of my success to living through these experiences.

When people reduce me to inspiration porn, what they’re often missing is how integral my disability, my queerness, and the things I’ve survived are to the person I am today. My success and my struggles are all wrapped up together, and my identity can’t be reduced to “moving past” or “overcoming,” when the very reason I’m so passionate and driven is because I’m there, in the trenches, living life as a disabled, queer survivor.

It’s not in spite of what I’ve gone through that I succeed. It’s because of.

Alaina Leary is a native Boston studying for her MA in Publishing and Writing at Emerson College. She's also working as an editor and a social media designer for several magazines and small businesses. Her work has been published inCosmopolitan, Marie Claire, Seventeen, BUST, AfterEllen, Ravishly, BlogHer, The Mighty, and more. When she's not busy playing around with words, she spends her time surrounded by her two cats, Blue and Gansey, or at the beach. She can often be found re-reading her favorite books and covering everything in glitter. You can find her on Twitter and Instagram @alainaskeys.

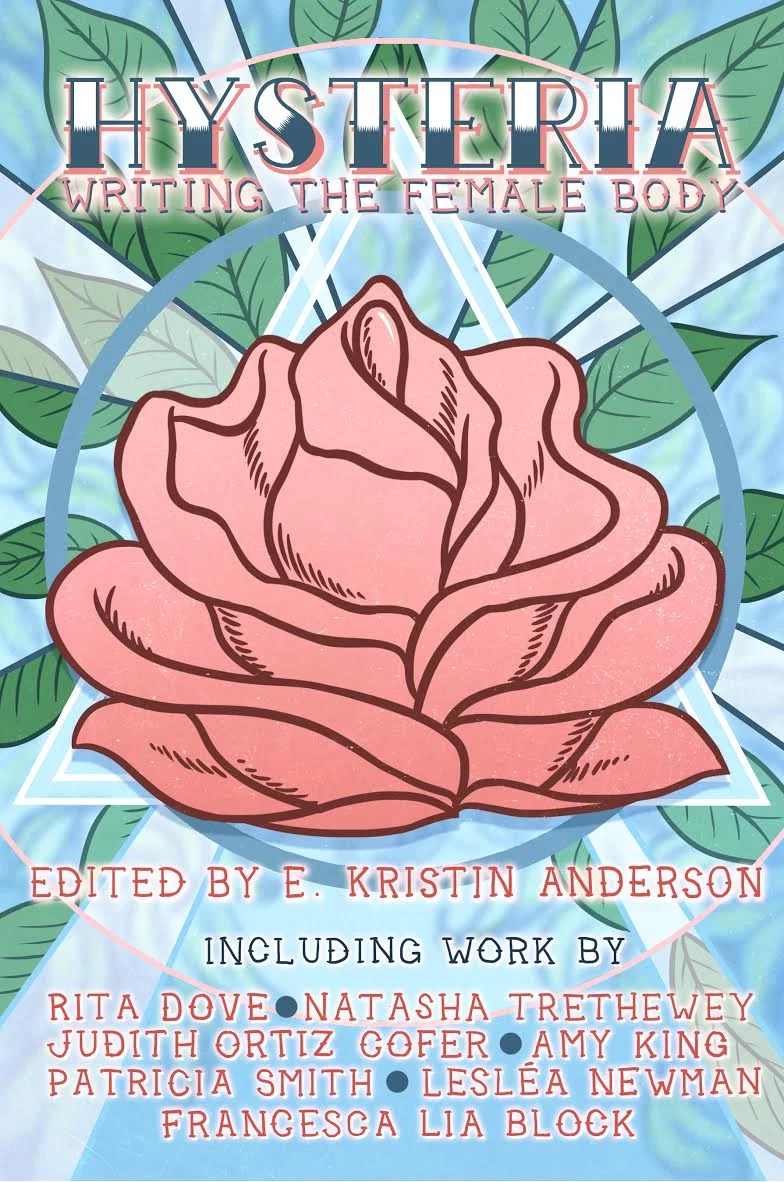

The Cover Reveal for Lucky Bastard Press' Hysteria Anthology

Check out the exclusive cover reveal of Lucky Bastard Press' HYSTERIA anthology + enter to win a copy & bonus swag.

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

As both editor of Luna Luna and a contributor to Hysteria (an anthology of writing by female and nonbinary writers about their biology and anatomy and experiences with the body) I thought doing a reveal of their cover would be a great way to create a dialogue about this amazing collection of works. When E. Kristen Anderson presented the idea, I thought Luna Luna would be the perfect home for this.

Want your own free copy? Here's how!

1. Tweet or post a link to their fundraiser (or just write a super cute supportive tweet/post about the book).

2. Leave a comment below (with the link to your social post) + your email (so we can contact you!)

3. We'll pick a comment at random and send you the anthology, along with E. Kristin Anderson's gorgeous Lana Del Rey-inspired poetry collection (I've read it, blurbed it and adore it).

LMB: Who is the team behind Hysteria?

EKA: Allie Marini and Brennan DeFrisco gave me the platform to do this anthology when they green-lighted the project at Lucky Bastard, but it’s basically been me and the contributing authors. Allie and Brennan definitely helped with soliciting some fine voices I hadn’t heard of, and have been a great support, so I don’t want to be like, oh, hey, this was all me. But in a lot of ways it was. And it’s been both intense and rewarding.

I think what Hysteria does so well is take a topic that is hard to write about successfully and inclusively (the body and notions of femininity, in many cases) and make it subversive; it's envelope-pushing. What sort of bodies did you want to include here?

It kind of started with me writing erasure/found poetry from tampon packaging. I’m not even kidding. And Allie and I got to talking about a tampon/period anthology and we expanded the idea out to other body-related themes. We went from there.

I certainly did want to push the envelope. But what I found interesting is that some poets that I thought would submit told me (before later submitting and being selected for the anthology) thought their work wouldn’t be edgy enough. And my answer to everyone asking “would my work be suited for HYSTERIA?” was “there are many ways to experience the female body/being female.”

So I wanted lots of bodies. Including nonbinary and trans bodies, which was a little harder because I know that many of these writers have been excluded from this type of project. We went looking, and we found some amazing work.

Tell me a little bit about what spoke to you when selecting content?

Diversity of topic and voice was really important to me. I wanted—like I mentioned above—lots of experiences to be represented. There was a point at which I think I posted on my original call “no more period poems, we’ve got that covered!” But it wasn’t just about topic. It was also about style. There’s some experimental work in HYSTERIA that I don’t know I would have read or picked up if I were shopping in a bookstore, but that I’m glad showed up in my inbox because it spoke to me within the context of this project.

And diversity of cultural background was important to me, too. And by cultural background I mean race, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation and gender identity. I really wanted pieces about wearing a hijab. About bat mitzvahs. About non-hetero sex. I hope I did a good job with this. I hope I found authors and pieces that people enjoy and relate to and learn from.

What do you think the anthology speaks to in the climate we're in right now – as women, as creatives?

You know, every day it feels like there’s something else going down that I want to throw this book at. Women being told their dreadlocks are unprofessional. Women’s tough questions being written off as the result of PMS. (Looking at you, Trump.) Bills being passed that could undo years of work for women’s rights. People trying to tell me, personally, that “hysterical” is just a colloquialism and not a gendered hate word. Folks thinking that just because we’ve achieved parity in one little bubble of the lit world that sexism is over for all of lit. The VIDA counts for big magazines (hello, the Atlantic) and smaller magazines. Songs on the radio. Things I overhear kids say to each other when I write at the Starbucks that’s next to the middle school.

So often we think, well, it’s just a joke. It’s just one guy. It’s just one magazine. It’s just a handful of nut-jobs. It’s just the radical right, and their minds can’t be changed. But! But. Sexism is so ingrained in us that even you and I do sexist things every day without thinking of it. I think I’ve referred to a woman I didn’t like as a bitch even this week.

I hope HYSTERIA gives us a place to talk about uncomfortable subjects, to start and continue conversations with ourselves, our daughters, our peers—but I also hope it’s a place to find comfort and community. Maybe the patriarchy isn’t listening. But maybe we can rally anyway.

I was particularly thrilled to write for this anthology. I am alongside some amazing writers and also emerging ones. How did you vote for pieces? Was this about making a space for all voices, new and established?

I read and selected the submissions myself. Aside from the solicitation—which I did ahead of time, before sending out the call—I just wanted to make sure we had everything covered. I didn’t care if folks were famous or brand new, just that the work was good. And I’m super fortunate that we did get some big names for the anthology. People who said yes when we reached out and asked. But I’m also super fortunate to have new voices with new things to say. Because that’s what community is about and I think that, in a way, that’s what HYSTERIA is about, too.

What are the plans for the anthology?

I’m hoping to set up a launch party here in Austin, TX when the book is ready. I think it will be a good time, and hopefully, as many contributors as possible can come and read. We’ll definitely be sending out review copies and doing our best to entice booksellers and librarians. We want this book in as many hands as possible. It’s a beautiful book if I don’t say so myself.

How will donations help?

The funds from the Indiegogo campaign are going to help us pay some of the up-front costs (like hiring our cover artist, Jodie Wynne, and the Adobe Cloud account we had to open to manage the many, many contracts for the individual authors) as well as printing. But the biggest reason we wanted to do an Indiegogo was so that we could pay our authors better. So if you can help us out with that, that would be amazing. Should we exceed our goal, any extra funds will go toward a launch and/or future anthology projects at Lucky Bastard Press.

Tell us what it's like to work with Lucky Bastard Press.

Lucky Bastard was founded by Allie Marini and Brennan DeFrisco and somehow I tricked them into letting me do an anthology with them. They really gave me free reign, which was scary but also really thrilling. I’m now on board with LB as a full editor, but at the time it was just, here, EKA, make a book. So I did. And I’m really excited that it’s with a press that is all about the underdogs and the long-shots. Isn’t that how many of us feel, as artists, especially as women? Lucky Bastard is here to champion the weirdos. And, in this case, it’s the hysterical weirdos that we want to show the world.

The writer list, as provided by

Lucky Bastard Press:

E. Kristin Anderson

Gayle Brandeis

Allison Joseph

Christine Heppermann

Lynn Melnick

Lizi Giliad

Lisa Marie Basile

Kia Groom

Laura Cronk

Alison Townsend

Amy King

Kirsten Smith

Aricka Foreman

Dena Rash Guzman

Kate Litterer

Paula Mendoza

Sara Cooper

Kirsten Irving

Erika T. Wurth

Natasha Trethewey

Kelli Russel Agodon

Kenzie Allen

Rita Dove

Francesca Lia Block

Patricia Smith

Lesléa Newman

Erin Elizabeth Smith

Tatiana Ryckman

Janna Layton

Mary McMyne

Sarah Lilius

Jennifer MacBain-Stephens

Elizabeth Onusko

Katie Manning

Sandra Marchetti

Sarah Ghoshal

Ivy Alvarez

Heather Kirn Lanier

Jane Eaton Hamilton

Jessica Morey-Collins

Sally Rosen Kindred

Laurie Kolp

Gabrielle Montesanti

Sonja Johanson

Meghan Privitello

Deborah Bacharach

Juliet Cook

Sarah Henning

Trish Hopkinson

Alina Borger

Christine Stoddard

Hope Wabuke

Nicole Rollende

Roxanna Bennett

MK Chavez

Catherine Moore

Jesseca Cornelson

Karen Paul Holmes

Lisa Mangini

Shevaun Brannigan

Martha Silano

Jen Karetnick

Emily Rose Cole

Sarah Kobrinsky

Addy McCulloch

Mary Lou Buschi

Sarah Frances Moran

Ellen Kombiyil

Shanna Alden

Julie "Jules" Jacob

Ariana D. Den Bleyker

Sheila Squillante

Jeannine Hall Gailey

Randon Billings Noble

Mary-Alice Daniel

Sarah J. Sloat

Minal Hajratwala

Shikha Malaviya

Elizabeth Harlan-Ferlo

Leila Chatti

Sarah B. Boyle

Jennifer K. Sweene

Nicole Tong

MANDEM

E.D. Conrads

Samantha Duncan

Susan Rich

Kristen Havens

Judith Ortiz Cofer

Hila Ratzabi

Joanna Hoffman

Elizabeth Hoover

Letitia Trent

Camille-Yvette Welsch

Erin Dorney

Shannon Elizabeth Hardwick

Anna Leahy

Majda Gama

Erin Lorandos

Amy Katherine Cannon

Nicci Mechler & Hilda Weaver

Mary Stone

Jessica Rae Bergamino

Jennifer Givhan

Hilary King

Sara Adams

Bri Blue

Vicki Iorio

Natasha Marin

Tanya Muzumdar

Miranda Tsang

Jessica L. Walsh

Lucia Cherciu

Melissa Hassard

Nora Hickey

Dorothea Lasky

Siaara Freeman

Deborah Hauser

Suzanne Langlois

Eman Hassan

Amber Flame

Lisa Eve Cheby

Soniah Kamal

M. Mack

Teresa Dzieglewicz

Geula Geurts

Jennifer Martelli

Carleen Tibbetts

Katelyn L. Radtke

Cleveland Wall

Stacey Balkun

Autism Isn't a Dirty Word, But It Feels Like One

I’m sitting at my computer desk when the email appears in my inbox.

“We’re honored to invite you...” It’s my undergraduate university, asking me to appear as an alumni speaker at the annual Spring Gathering.

I already know what my friends will say when I tell them about it. “Wow, but you’re only a year out of school!” “I told you, you’re the most successful person in our class!”

I stare at the email, blinking several times just to see if it will disappear.

Read More7 Books You'll Actually Enjoy Reading

These are books I've read in the last few months. I loved them, so I want you to love them too.

Read MoreThe Night We Didn’t Fall In Love

A female body in mom jeans looks at a water color of Bianca Stone’s depicting the three fates. Only one faces us and says in her speech bubble, “I’m filled with rooms I’ve never seen before.” It hangs in my living room. I am the female body, a room I see so much of I don’t see it at all. I see it so little that I’m usually digging my nails into my skin in order to get anything practical done without overwhelming anxiety. How do I get this out of the room? I got Netflix binge-streaming House of Cards to distract me from my loneliness and this. I miss something I’ve never had, stupid saudade. How much of the wine bottle has been drunk and will it get me to the end of the night?

Read MoreArt as a Blend of Many Truths: Why We Shouldn't Question Beyoncé's Narrative

To tell a story (even your own), in a way, is to tell someone else’s–if it were only hers, how could we connect? How could we expect her to own every word? Why must it be debunked or defined at all?

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

Lemonade emerged from darkness at a time of political unrest and volatile racism. For many, I’m sure, it also comes about as a Spring story of rebirth and the divine self; Lemonade’s grief is collective and personal–the story she weaves is everyone’s story, an eternal hurt, the story of mothers who broke at the hands of men, the story of a girl who was too naive, the story of women who take back their agency.

Everyone keeps worrying about the truth; what’s the truth? Is the artist being cheated on? Did she forgive him? Why is he seen, on camera, stroking her ankles, kissing her face? What if it’s about her own mother? What if this is a machine? What if the artist is exploiting rumors about her marriage–and feeding the beast that way? What if the beast isn’t her own?

The fact is that the artist doesn’t always need to have experienced everything first-hand. Certainly, Beyoncé is building a world, one that is universally understood enough to be appreciated: the grief of lost love, the grief of being lied-to, the relentless anger, the baptismal, personal resurrection, the lover's possible forgiveness, the healing power of culture.

One of the ways she builds this world is by featuring the words of poet Warsan Shire. In a New Yorker piece that pre-dated Lemonade by several months, it is clear that even Shire doesn’t claim her work is entirely autobiographical:

“How much of the book is autobiographical is never really made clear, but beside the point. (Though Shire has said, “I either know, or I am every person I have written about, for or as. But I do imagine them in their most intimate settings.”) It’s East African storytelling and coming-of-age memoir fused into one. It’s a first-generation woman always looking backward and forward at the same time, acknowledging that to move through life without being haunted by the past lives of your forebears is impossible.”

This is how art works. As a poet, I play a character and the character plays me–always vacillating between this point in time and that point in time and heart, time owned by me or time owned by someone else, heart owned by me, and heart owned by other. It’s the million ghosts that tell the story, and they’re needed to give it dimension.

We should give artists–and I’m calling Beyoncé an artist, here, and if you don’t like that, bye–the ability to make their art into something alchemical; a little this, a little that. It’s the potion of the collective unconscious, that which is passed down by ancestors, mixed with our consciousness and our memories, our collective experiences of love and sorrow. To tell a story (even your own), in a way, is to tell someone else’s–and if it were only hers, how could we connect? How could we expect her to own every word? Why must it be debunked or defined at all? Why isn't it ok to tell the story of something bigger?

In Lemonade, Beyoncé handles the past–through her grandmother’s voice, Shire’s voice, the history of race in America, the way love has treated her–the present, and the future: a future of hope, a heaven that is a “love without betrayal,” the dissolution of racism, the reclaiming of feminine power, nature as a symbol of forward momentum.

I think we are begging for these many voices, these many moving parts she has woven; I am happy it was a collaboration. It gives me hope for art.

And don’t drink the Haterade: “It’s her producers, it’s the songwriters, it’s the people she hired.” When people reduce any artist to this, they’re reducing art, which I suspect is antithetical to their whole point. Being an artist takes knowing how to harness the power of many, it takes knowing how to build a vision, and it takes knowing how to embody that world. Nothing can be done alone.

The time you spend questioning her writing credits, her veracity, her money – is time you could be devoting to the very moving art created by Beyoncé and her team – poets and directors and the powerful Black women she features. It says something, and if you give it the space, I’m sure it will talk to you.

Lisa Marie Basile is a NYC-based poet, editor, and writer. She’s the founding editor-in-chief of Luna Luna Magazine, and her work has appeared in The Establishment, Bustle, Hello Giggles, The Gloss, xoJane, Good Housekeeping, Redbook, and The Huffington Post, among other sites. She is the author of Apocryphal (Noctuary Press, Uni of Buffalo) and a few chapbooks. Her work as a poet and editor have been featured in Amy Poehler’s Smart Girls, The New York Daily News, Best American Poetry, and The Rumpus, and PANK, among others. She currently works for Hearst Digital Media, where she edits for The Mix, their contributor network. Follow her on Twitter@lisamariebasile.

Finding an Unlikely Home in NYC

The small courtyard is crowded with splintered cafeteria tables cluttered with various items in various states of cleanliness: worn black Reeboks, outgrown children’s clothes, hoards of garish costume jewelry, books that should have been long ago returned to a library, disc-man headphones with slightly gnawed on connection jacks, and, the most archaeological finding of all, teetering pillars of VHS’s stacked haphazardly atop each other like ruins. There does not appear to be any connection amongst the miscellaneous items shoved onto a table save for the fact that they all belong to the flea market vendor’s past. All together they tell the story of a life; a story that is for sale; memories for a dollar fifty. The Immaculate Conception courtyard, home to the flea market on weekends, cramped with used objects and worn people, is hemmed in by buildings of prestige on either side of it.

Read MoreReview of Atoosa Grey's 'Black Hollyhock'

Black Hollyhock, Atoosa Grey’s first poetry collection, faithfully adheres to its title. While voluptuously organic, it also contains a dolorous underside. Grey’s image-driven poems, imbued with symbolism, navigate territories within territories -- those of language, identity, motherhood and the body. She deftly renders a world nuanced with languid musicality and replete with questions. She asks us to consider the currency of words, to find the sublime in the mundane, and to recognize the inevitability of rebirth and resurrection throughout our lives: “The body has its own way of dying / again / and again.”

Read MoreInterview with Roberto Montes on 'I Don’t Know Do You'

Roberto Montes’ "I Don’t Know Do You" was named one of the Best Books of 2014 by NPR and was also a finalist for the Thom Gunn Award for Gay Poetry from the Publishing Triangle. This says a lot for a first book. But there is so much more here. Montes’ poems speak eloquently on the trials and travails of living in our modern society, of growth and change, of politics and poetics, and mostly of love in its many forms and formats. I consider myself lucky to call Roberto a friend and colleague. We graduated together in 2013 from the New School’s MFA program. Lucky ‘13 – I like to call it. Our graduating class of twenty-seven poets has already made great inroads, at least seven of us have books out or forthcoming; and we’re all forging forward in our own ways while learning how to navigate the strange and exciting world of Poetry and Publishing.

Read MoreThe Trials of Writing Haibun About the Salem Witch Trials

Hands down, the best decision of my life was joining a low-residency MFA in Creative Writing program. When I think about my experience, I imagine Mike Teavee from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. My poems, like Mike, started out normal sized and a bit naive. Then they shrunk. This tiny poem phase didn’t so much reflect the length of the verse, but instead the humbling of my ego. Everywhere I went, I met beautiful poets and read amazing collections. I currently take in every bit I can of anything that might even closely resemble a poem so that my tiny, metaphysical mind-poem can grow. And that’s just what it’s doing.

Read MoreDara Scully

Nightingale And Swallow Part II, Fiction By Taylor Sykes

When he’s back in the store and I’m alone again, I let myself lean into the worn leather steering wheel, clinging to it like a body. I can’t keep myself from crying when I think about that boy and what Caroline did to him. So I cry until it rains and then until it rains harder, until the sound of wind and water striking the truck is louder than I could ever be.

Read MoreDara Scully

Nightingale And Swallow, Part I, a Fiction Piece by Taylor Sykes

His lips look purpled already, but it must be the moon’s coloring coming in from the window. I push a puff of smoke into his spit-soaked face. It hits like a burst of water. Then comes the heft in my chest, a weight the size and shape of a fist. Before I can think too much about it, I push him on his side, face down.

Read MoreWitchy World Roundup: April 2016

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. She is the author of Sirs & Madams (Aldrich Press, 2014), The Gods Are Dead (Deadly Chaps Press, 2015), Marys of the Sea (forthcoming 2016, ELJ Publications) & Xenos (forthcoming 2017, Agape Editions). She received her MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. She is also the founder of Yes, Poetry, as well as the chief editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of her writing has appeared in Prelude, The Atlas Review, The Huffington Post, Columbia Journal, and elsewhere. She has lead workshops at Brooklyn Poets.

Read MoreHow to Reclaim Physical & Mental Safe Spaces

How to reclaim safe spaces, both physical and mental, after sexual assault or a traumatic event.

Credit: The Write Type

BY ALAINA LEARY

Going into Boston is normally quite a calming experience for me. I grew up just outside the city, so my childhood was filled with frequent train trips to go shopping, take walks and see museums.

This day, however, was different. As I approached the mall, I started seeing more and more people dressed in familiar outfits, mainly mimicking anime and video game characters, with some pop culture, sci-fi and fantasy thrown in: they were cosplayers.

I’m all for cosplaying. I love the fact that people put so much passion and effort into something they care about. I have a cousin and several acquaintances who cosplay for conventions every year, and they go all out.

So what was my problem? To be honest, I was afraid I’d see my rapist at the convention. And I was even more afraid I wouldn’t recognize my rapist until it was too late, because they’d be wearing cosplay. I was terrified we’d come face-to-face and I wouldn’t even know it until we were in close proximity.

With all the recent talk about trigger warnings in classrooms, the idea of a “safe space” comes up frequently among conversations in my generation. People seem to genuinely care about the physical and mental well being of others, which is refreshing. But what does it mean to create a safe space, and what happens when your safe space is also occupied by the source of your trauma?

These are some of the questions I had to ask myself before attending the con, while I was at the con, and after I’d returned home.

1. How do I define what a safe space is?

Ideally, everywhere would be a safe space. But, in general, I regard safe spaces as places I feel comfortable. Places that feel a bit like home, a bit like a community, to me. In my eyes, writing and the arts have always been a safe space. I use writing and other creative arts to feel better when I’m upset. They’re therapeutic.

The anime and fantasy world was always a safe space for me. It’s a community that tends to be welcoming of oddballs, and of queer people, both of which I am. I felt it was easy to connect to fictional characters, especially when I broadened myself up to international media rather than just American primetime television. While all my friends were watching Grey’s Anatomy as teenagers, I had a whole host of LGBTQ+ anime shows I was obsessed with.

The question, then, becomes: How can something I care about be a safe space when my assailant also cares about it?

This is definitely something I’ve struggled with. Part of the reason my rapist and I became friends—long before I ever suspected she’d hurt anyone in that way—was because we bonded over fantasy elements. We both liked to write. We both liked to draw. We both watched anime, and read fantasy YA on the regular.

After I was raped, my trust was destroyed. Although my rapist and I hadn’t been friends in years by that time, and I’d known she was toxic for a long time, my main problem was that I felt betrayed by one of my own. My rapist was a queer, cosplaying writer. How could I continue to feel safe among other creative types, among other fantasy-lovers, after something like this?

2. How do we reclaim our safe spaces?

I didn’t feel safe in my own body for a long time after my rape. Worse, though, was that I didn’t feel safe in my own head or my own personality. My mind wanted to fight against so many aspects that make me who I am, simply because they reminded me of my rapist. I didn’t want to write anymore. I didn’t want to read fantasy. I didn’t want to watch anime. I didn’t want to be artsy.

It took me a long time to realize that these things, for me, were a metaphysical safe space much in the same way that my favorite room in the house, or a chair by the beach, also was. They provided me with comfort, and they’d always felt like a home to me. Somewhere I knew I’d be protected. Somewhere I could return to, if the outside world got rough.

Once I realized these experiences meant safety to me, it was hard to let go of them. My instinct was to fight them: to kill anything that even vaguely resembled my rapist. After the rape, I stopped all creative writing. I didn't write a single word that wasn’t assigned for class. My metaphysical safe space had been taken away. There was no home to go to, and things in the outside world were rough, because I was dealing with the aftermath of a serious trauma.

I had to ask myself: How can I make this place, even though it’s not a physical place, mine again?

I tried to recreate the worlds I’d been a habitant of, but in a new light. Although these worlds were often solitary, they were also strongly reminiscent of community. I’d made friends who were also writers, artists, fantasy nerds.

That’s what I decided to do again. I recreated the community in a new safe space. My girlfriend, who is also a writer, artist, fantasy YA reader, and anime watcher, helped me do this. She saw how difficult it was for me to enjoy things that were so central to my personality, so we created a new safe community. We invited other English majors and writers to take classes with us, and to go with us to on-campus writing workshops and creative work readings. We asked our close friend and roommate to watch an anime series with us, just to give it a shot. (She ended up loving it.) We recommended fantasy books to friends and then talked about them.

After I started doing these things again in a safe space with others who understood my trauma, I was slowly able to do them on my own. I took my first class as an English major about a year after my rape, with my girlfriend and several friends in the class. I wrote a poem for the first time without being instructed to by a professor. I let my friends read it, and we all laughed and joked and had fun.

The thing about trauma is that a part of me was worried the entire time I was doing these things. I knew it was possible to re-trigger myself, and cause a PTSD panic attack at the memory of enjoying these things with someone who later destroyed my trust. It was necessary to ease myself back into the process of enjoying my former safe spaces, rather than drown myself in it. It was a slow process, one foot in front of the other.

3. How can we prepare for triggers of the past trauma?

This is the question I asked myself every day for weeks before attending the convention. It was the first time I’d been in five years, not just because of the trauma, but also because I was studying in college in the middle of nowhere and it was impossible to get back to go to it.

Now that I’m living in Boston again, I was determined to go to the convention. I wanted to go, dammit, and I wouldn’t let my trauma stop me! That didn’t stop my brain from sending me daily nightmares about seeing my rapist on the train, at the mall, in a crowd of faces.

So what can we do to prepare ourselves for situations we think are bound to be a little more stressful, and which may re-trigger past trauma?

In my case, I had reason to believe my rapist—who I haven’t seen since the attack—would be at this particular convention, although I have no idea if my suspicions were accurate. She tends to go every year, though, and almost always dresses in cosplay.

Attending this con was a big step. It involved the possibility of seeing my rapist, and I knew because of the sheer size of it, it might re-trigger trauma even if I didn’t end up seeing her.

I was right.

But that didn’t make the experience not enjoyable. What I’ve learned, in my four years now as a rape survivor, is that there are so many moments that can re-trigger trauma. An unexpected nightmare that wasn’t caused by anything. A rape scene in a television show or a movie. A mention of my rapist in casual conversation by someone who doesn’t know. But my life is still worth living—and I love living it. Even in the moments when I’m dealing with the aftermath, with the PTSD, I love being here.

The con was stressful. A few times, when I thought I saw someone in cosplay who resembled my rapist, I had small panic attacks. I escaped into a mall Barnes & Noble for a while to calm down. Books have always been a safe space for me, too. I treated myself to Au Bon Pain, my favorite Boston café, which has never reminded me of my rapist. I ate a lox bagel. I drank soda. I took deep breaths.

The best way to prepare for a possible triggering of trauma is to be aware. Know your triggers, if you can, and what happens when they occur. Do you have panic attacks? Severe anxiety? Do nightmares crop up as a result? Do you dissociate? These are all things you should try to keep track of, as it happens, even though it may seem uncomfortable. It’s useful for situations where you have an idea that it may happen.

Also be prepared to practice self-care. I bought myself food that I enjoy, and took time away to surround myself with books. I had conversations with my girlfriend about our favorite anime and manga. I treated myself to dinner at my favorite restaurant. I went home, and went to bed early to get a good night’s rest. I knew it would be a stressful day for me, so I prepared ahead of time to be ready for self-care.

Safe spaces aren’t as clearly marked as you’d assume—sometimes, the spaces that were safest to us aren’t always trauma- and trigger-free. That’s why it’s increasingly important to practice mindfulness, be prepared with self-care tips, and above all, know yourself. Know what works for you, what doesn’t, and what your limits are. Take care of yourself and, if you feel comfortable, make others aware of what happened and the potential for re-triggering so they can be a support system for you.

Alaina Leary is a native Bostonian currently completing her MA in Publishing at Emerson College. She's also working as an editor and social media designer for several brands. Her work has been published in Cosmopolitan, Seventeen, Marie Claire, BUST Magazine, Good Housekeeping, Her Campus, Ravishly, The Mighty, and others. When she's not busy playing around with words, she spends her time surrounded by her two cats. She can often be found re-reading her favorite books, watching Gilmore Girls, and covering everything in glitter. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter @alainaskeys.