Monique Quintana is a Xicana writer and the author of the novella, Cenote City (Clash Books, 2019). She is an Associate Editor at Luna Luna Magazine and Fiction Editor at Five 2 One Magazine. She has received fellowships from The Community of Writers at Squaw Valley, The Sundress Academy of the Arts,and Amplify. She has also been nominated for Best of the Net and Best Micofiction 2020. Her work has appeared in Queen Mob’s Tea House, Winter Tangerine, Grimoire, Dream Pop, Bordersenses, and Acentos Review, among others. You can find her at [www.moniquequintana.com]

Read MorePhoto of Lisa Marie Basile by Christine Stoddard for Quail Bell Magazine

Two Selves: Life With Chronic Post-Traumatic Stress

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

A piece for World Mental Health Day

In the homeless shelter’s childcare center, I was the oldest child. I was 12. My mother, brother, and I lived there for nearly a year, after having shared a room with another woman at the YMCA down the road. My adolescence was communal spaces and tiny rooms and my mother taking us to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, methadone clinics, and day-long out-patient treatments.

Looking back, the childcare volunteers at the shelter were warm and loving. I think, now, how they must have felt with a dozen traumatized children on their hands. There was the boy who stayed at the shelter after his mother was brutally beaten by his step-father. There were the twins, whose mother was pregnant and detoxing. The baby didn’t end up making it. And there was my little brother, a soft and pale child who was born into chaos and still remained loving and gentle and quiet.

Not me. I cried hysterically into strangers’ arms. I fell apart at every turn, even if I did it private. I overreacted at any noise.

A memory: One night, we watched Titanic in that childcare space. I lost it when Jack died. Not because it’s sad — because of course, it’s sad — but because I couldn’t handle loss. I couldn’t fathom the endless, giant, gaping wound that is death. Change. Lack. That we live until we don’t. That we exist until we simply fall into the sea.

Loss was a language I’d learned early but had no way to speak it out of me. I couldn’t translate it because I was a child, and because it never ended. I’d only ever witnessed extreme poverty and countless evictions. Parents shooting up. A fatherless household. Dead grandparents. I was molested as a child. And later, I’d live in foster care, separated from my brother. My brother moved three times. I moved twice. And then the death of nearly everyone in my family. By my 30s, I would vacillate between numb and broken.

I had never known stability, safety, softness — and anytime I’d watch death, loss, or change in a film or read about it in a book, I’d have a visceral, nauseating reaction. My body was wired this way. I longed for stability, but my body had been uprooted too often.

When other kids daydreamed of crushes and cars, I was thinking of how I’d decorate a bedroom of my own. My own space, filled with books and art and things that wouldn’t be collected into garbage bags and moved from place to place.

I was both addicted to and dying from all this loss — a disease I wouldn’t realize or acknowledge until well into my 20s.

***

In college, I was dumped by a guy I liked. His name was Joey. And let’s be serious; he was a loser, as most college guys are.

Of course, I had cheated on him. And I’d cheated on the one before him. And the one before him. Destruction was my language, my power pattern. It made sense to dirty what I loved. It fed me. If I poison the crops, then they could never grow, and if nothing could ever grow, nothing could die. It was that simple, an ideology that would serve me until it didn’t.

But when he broke up with me, I stopped sleeping. I stopped eating. My naturally curvy body became brittle and slight. I’d go home to visit family in New Jersey, and when I’d drive, I’d have to pull over to the side of the road to cry. No, not cry — sob. I’d sob. I’d sob because the loss, any loss, was a rejection, a reminder that things end, that things go away. The breakup, which shouldn’t have affected me nearly as much as it did, pressed the “you no longer have this” trigger. Loss was my perpetual event horizon.

In a therapist’s office, I said, “No one understands the gravity of this breakup.” But she said, “I think they do understand that it hurts you, but they don’t understand why it hurts so much, or what’s behind it.”

I instinctively knew what she was saying to me. It didn’t surprise me that the fear had followed me through the years. That my black hole of childhood was closing in on everything I engaged in. That the immensity of grief, for me, never took the form of one grief, but every single grief ever felt — all coming up to the surface, bearing its teeth and claws, during a routine college breakup. I just had no idea what to do with the immensity.

"But I just can’t stop it,” I told her. “Everything feels like I’m spiraling out, and no one will ever save me.”

***

One day, I stopped running from the fact that I was hurt. I needed to excavate the self. I got sick of lying to people about my childhood. I got tired of going icy when something hurt me. I got tired of not writing about the thing I needed to write the fuck about.

I wanted to know my real self, the self buried under the rubble of every single trauma and every single hyper-reaction to anything resembling pain. Who was in there? Could these two selves live together harmoniously? Could I look back and forward at the same time?

***

I have had foster care dreams since the day I entered the system. From 10th grade until I graduated (a year after my peers, as I’d stayed back), I lived in strangers’ homes. I always felt dirty, ashamed, like a boarder. I’d sit with my smudged mascara and books on the floor of my bedroom when my foster mother would call down to me, “it’s time for dinner!”

It was disassociative, my body floating down the stairs, disconnected. Whose house was this? Whose life was this?

Whose sofa, whose carpets, whose food?

I lived in this disassociative state for years and carried it into adulthood. My dreams are often of being forced to go back into that home, of never feeling at home, of feeling faraway and ripped from everything stabilizing and normal.

I often dream that I’m being taken from my current apartment in New York City, as a 33-year-old, by a truancy officer, and told that I must go back into foster care. It’s just the way the system works, they’d say. And I’d have no choice. No one fights for me to stay, not even my partner.

I dream of putting my things into a single garbage bag. There’s only ever one bag. What the fuck do I bring? What do I have to let go of?

No more job. No more apartment. No more life in New York City. No more writing. I’d have to resume life as that little girl, the one who was shuttled, at the hands of adults who should have known better, between disparate realities.

Sometimes I journal about these nightmares. I sit quietly and tell myself that it’s not real right now. That I’m right here. I’m right here. And I mostly believe it.

***

For a long time, I didn’t realize that I was suffering from mental health issues. I just thought I was a weird, poetic, old soul who’d been through some shit. I was just different. I was rough around the edges.

But the fact is, I live with chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. For me, this presents as nightmares, flashbacks, severe disassociative episodes, extreme responses to situations, and self-destructive behavior. When I was diagnosed in my mid-20s, I refused to tell anyone, thinking I was somehow pathetic, not strong enough to move on, too sensitive to let it go. But it’s not so.

Chronic PTSD is valid. It’s the result of exposure to chronic and repetitive trauma, especially during one’s formative years. It’s the result of not having access to proper care and support. It is not about being weird, artistic, poetic, different, sensitive, not strong enough, or broken. It’s not about living as a trope or wearing a character’s mask. It’s not about romanticizing elements of the self.

In PTSD and CPTSD, our brains are literally and actually rewired by trauma.

As Beauty After Bruises says:

“Complex PTSD comes in response to chronic traumatization over the course of months or, more often, years….While there are exceptional circumstances where adults develop C-PTSD, it is most often seen in those whose trauma occurred in childhood. For those who are older, being at the complete control of another person (often unable to meet their most basic needs without them), coupled with no foreseeable end in sight, can break down the psyche, the survivor's sense of self, and affect them on this deeper level. For those who go through this as children, because the brain is still developing and they're just beginning to learn who they are as an individual, understand the world around them, and build their first relationships - severe trauma interrupts the entire course of their psychologic and neurologic development.”

Today, I scroll through mantras touted by all manner of ‘love and light’ gurus on Instagram and see, “You are not your past” or “Let go of your demons,” but I am not sure I agree with either.

I am my past, and my past is me — we are the sacred twins, Luminosity and Darkness. We are the veil, both lifted and oppressive. My demons, while they haunt me, also nourish my writing career, remind me of my empathy and resilience, and give me hope and vision. We are me. I am the demon. I am the slaughter.

None of us should have had to be resilient. And having developed greater empathy because of constant retraumatization is not exactly a fair fucking trade-off, and yet.

And I know this is the case in so many other people living with mental illness.

It wasn’t until I stopped running from the past — trying to cleanse it and scrub it and self-torture it and bloodlet it out of me — that I have come to live with it. It’s not easy, linear, or clean. It’s not that I don’t have nightmares or insomnia. It’s not that I don’t fully break down when I move houses or read about our overly-saturated foster care system or kids put into actual cages in the news. It’s not that I don’t often question my worth or my safety. It’s not that I don’t still deal with the fallout — debt, family addiction, family in and out prison. I still do deal with it. I am reminded of it every day.

But I reclaimed it now. I have made space for it to co-exist alongside my healing. I have realized it’s not one or the other. I have spoken my trauma into the world now, and it’s no longer festering inside me.

Living with CPTSD, for me, means realizing that it’s very much a valid diagnosis, that I wasn’t at fault for it, and that sometimes the horror takes over. But now I challenge it and I challenge myself when I feel like I’m falling. I reach out for support. I treat myself with respect and patience.

But mostly it means trying to make life a little more beautiful. To rebuild and reframe and breath — even when the devil is on my back. Even when I’m triggered. Even when I don’t feel it’s possible. It’s finding a sense of harmony with the shadow, not pretending everything is okay.

I’m finally giving myself a sense of home.

~

If you need support, please see our list of Resources here. You are loved.

Lisa Marie Basile is the founding creative director of Luna Luna Magazine--a digital diary of literature, magical living and idea. She is the author of "Light Magic for Dark Times," a modern collection of inspired rituals and daily practices and the forthcoming "Magical Writing Grimoire.” She's also the author of a few poetry collections, including 2018's "Nympholepsy." Her work encounters the intersection of ritual, wellness, chronic illness, overcoming trauma, and creativity, and she has written for The New York Times, Chakrubs, Narratively, Catapult, Sabat Magazine, Healthline, The Establishment, Refinery 29, Bust, Hello Giggles, and more. Her work can be seen in Best Small Fictions, Best American Experimental Writing, and several other anthologies. Lisa Marie earned a Masters degree in Writing from The New School and studied literature and psychology as an

On Being Told I Am Haunted

Kailey Tedesco is the author of These Ghosts of Mine, Siamese (Dancing Girl Press) and the forthcoming full-length collection, She Used to be on a Milk Carton (April Gloaming Publications). She is the co-founding editor-in-chief of Rag Queen Periodical and a member of the Poetry Brothel. She received her MFA in creative writing from Arcadia University, and she now teaches literature at several local colleges. Her poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. You can find her work in Prelude, Bellevue Literary Review, Sugar House Review, Poetry Quarterly, Hello Giggles, UltraCulture, and more. For more information, please visit kaileytedesco.com.

Read MorePublishing Your First Nonfiction Book: What I Learned

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

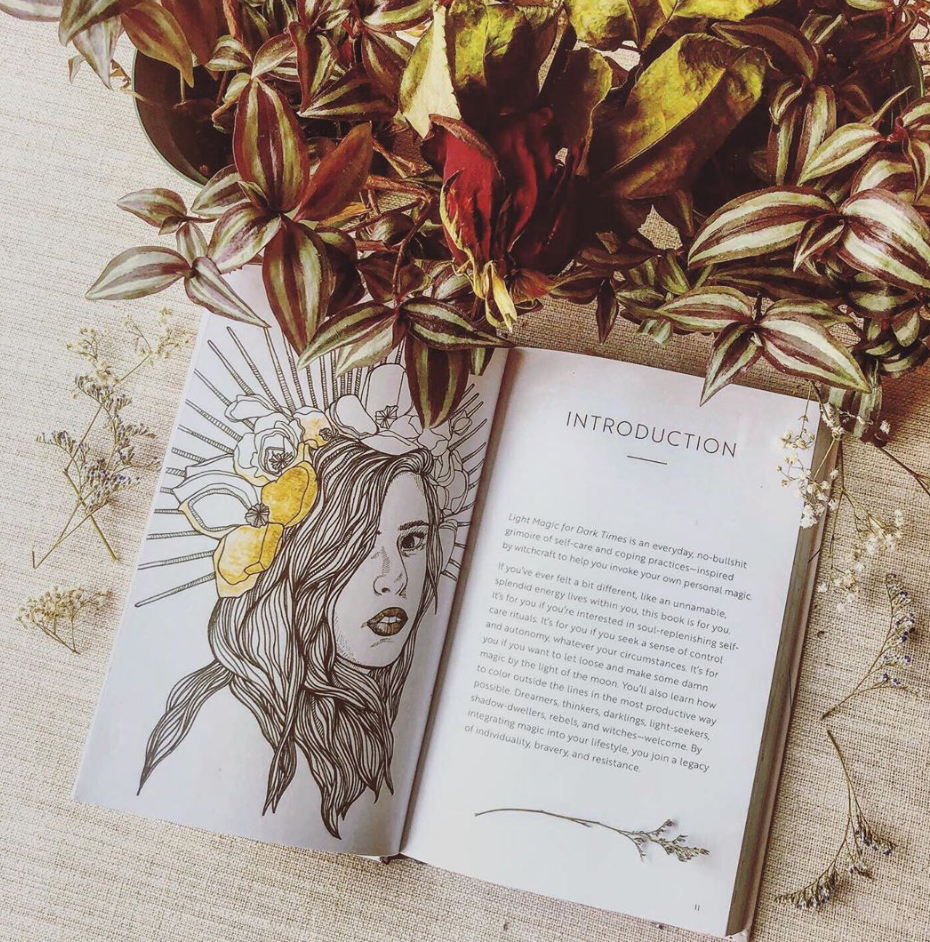

Light Magic for Dark Times came out a year ago this September. Watching it make its way out into the world (it was a global release in English speaking countries but it has made its way to many other places) this past year has been equal parts illuminating and surreal. It’s a privilege and an honor, and I will never get used to putting my hands on a physical book of my own. The younger me is in another realm losing her mind.

If you aren’t aware, Light Magic for Dark Times was born after an editor at Quarto Publishing read a few of my rituals here at Luna Luna — particularly one around grief. I’d just suffered the loss of a few family members and was aching to understand death, and to find some sort of meaning or comfort or peace. Ritual was a safe place for me, and it made sense to fold it into my experiences. It wasn’t perfect, fancy, elaborate, or even healing all of the time. It was a process I returned to again and again, and often felt unsure about. Because, in the deep belly of sorrow, grief, shame, or darkness, it’s hard to coming to a place of healing and let yourself be healed.

So when my editor asked me to write a longer book about practices and rituals for coping in crises, I said yes — reluctantly. I wasn’t sure if I was in the headspace to do so, even though I deeply wanted to. I wanted to write for everyone who needed a friend, and for every person, who, like me, was in pain or sifting though trauma. I found that writing through emotionality can be really activating.

When it came to the spell-writing component, I wasn’t an expert (nor will I ever be, and also: I’m not sure anyone really is, as everything is so subjective) on witchcraft, but I did want to fuse my interests and love for ritual, healing, writing, self-exploration and the archetype of the witch into one space. I wrote from my eclectic, secular perspective, and invited readers to amend every ritual as needed.

And so Light Magic for Dark Times was born.

And, magnificently, the writing of this book healed me at a time when I needed it most. It was contracted the very year I’d lost several people, saw my immediate family members fall ill, and was diagnosed with a chronic illness. The week it came out I left my job to embark on freelance. It was a book that marked an era. A before and after.

The book was a doorway in, a doorway out, a personal threshold. Here’s what I learned, a year out, from writing it. It wasn’t my first book, but it was my first non-fiction book (a strange animal, indeed), and because it was new for me, it taught me so, so much.

A book isn’t the end of a journey; sometimes it’s the very beginning.

When you have a book or completed project, it can be easy to get caught up in it’s being “finished.” In a sense, it is. It’s put to bed. It’s now a part of your past. An accomplishment. This is especially potent when you’ve seen obstacles — financially, psychologically, physically — on your way to getting there.

But writing a book doesn’t always feel like closing a chapter. In fact, one book’s ending opens another’s chapter, proverbially and, in many cases, literally. The growth that comes from one book is an extension of those pages. You expand, but your roots are found deep, deep within your first works. It’s a pivot point that asks you to plot your next steps, to reflect on your growth, to find pride and self-love in your work, to be even better at your next works. Think of your first book as a mirror; it will tell you what you need to know about yourself and your craft if you listen.

You will have some regrets.

Light Magic for Dark Times taught me a few things about what felt good and what didn’t. One, people want to be heard, loved, and seen. They respond to kindness and accessibility. They appreciate sincerity and they truly do read every sentence. They want to connect. They want to feel like they have a home in your pages. I loved that I got to learn this through writing and through connecting with my readers.

But I had some regrets.

Something I didn’t anticipate: Mourning the loss of my voice throughout the book. I’m a poet, so it was extremely difficult for me to scale down my lush prose so that a ritual or practice could fit on each page. That was daunting to me, and to achieve it, I felt I had to water down my language quite a bit. It’s taken some time to reconcile this fact and to understand that moving from poetry to this sort of nonfiction did require me to kill my darlings.

However, it only made me fight harder to preserve my voice and format for my next book, The Magical Writing Grimoire — which, I hope, has the space and breath to reflect my writing style much more.

The thing is, this wasn’t a loss. It was a learning experience, and it was a way for me to adapt, expand, and respect my voice, style, and capabilities. So, I’d urge you to learn from your first books, and give yourself some kudos for editorial fluidity and adaptability. Regrets happen. Try not to dwell on them. Let them catapult you.

Book sales, preorders, and numbers matter. Sorry, but it’s true.

Look — everyone always says that an author has to hustle, and that’s not a lie. I may be a Capricorn rising, sure, but I think everyone should put in the work.

Doesn’t your work deserve eyes?

I spent a wild amount of time promoting this book (and I still do), thinking of unique ways to share it without being excessive, grotesquely capitalist, or drenching my followers’ inboxes with “buy my book” requests. I likely have failed in some ways. I hand-made made gifts — little spell kits — for book buyers. I hand-wrote letters to editors. I emailed everyone I’d ever sort of worked with. I took a lot of time making connections with people, answering emails, setting up interviews. It needs to get done. And even I had a marketing manager!

All in all, the promotion of a book (especially if you don’t have an agent or a particularly hands-on marketing team) is fucking challenging. It asks you to seriously stop questioning yourself and to step into your power.

There’s a difference between ego or obnoxious promotion and transparent hustle.

Your book doing well can mean getting another book deal, being invited to host workshops, or pivoting your work into whatever direction you see fit. If that doesn’t interest you, that’s fine — but I’m talking directly to those who want to sell their books.

Here are some book promotion ideas and insights:

Preorder seriously matter. Getting preorders bumps your book in the algorithm on pub day. Seriously, get pre-orders.

Ask literally everyone for interviews. Email everyone you know for help. Develop a smart, quick email template that introduces yourself, the book, and any ideas you have for promotion. Keep it to 2-3 small paragraphs and send follow-ups.

Promote other writers. Don’t do this just for the kickback, though. When we give good we get good.

Develop a killer social strategy. You might hate social media, but that doesn’t mean you can ignore it. It’s not beneath you.

You don’t have to focus on sales to drive sales. If you create meaningful content and drop in the link to your book every once in a while, that’s smart. One tweet every three weeks is not enough, sorry, so use a tweet or post scheduler (and go forth.

A smart social strategy also means thinking about your Instagram grid (I know, kill me, please), the purpose of your pictures or captions, and thanking people who acknowledge your work on Instagram or Twitter. Seriously, thank your readers. I can’t stress this enough.

Join groups, forums and communities. Share your work in these groups when it’s appropriate and in a relevant fashion. Do make sure that your only interactions aren’t “Buy my book!” Yuck.

Spread your roots. Keep a blog. Create an interview series. Launch a podcast. Host a community group online. You can do all of this for free. The more of a root system you have, the more potential there is to share your work. This doesn’t have to be a capitalist venture; start from the point of wanting involvement and connection. If someone buys your book, even better.

Reframe your ideas of promotion: I’m going to just say it straight-up: Promoting your book is your job. You are not annoying people. I repeat: This is your job, even if we’re taught to separate art and money. Even if we’re taught that selling books makes us a sell-out. Even if you have been told that artists are supposed to suffer. No.

If you want to write books and not promote them, that’s fine — but if you want readers, you can’t expect them to come to you. Nope. You can’t expect your marketing team (if you even have one) to do all the grunt work. Because soon enough, another book will be released, and they will have other matters to focus on. Think of book promotion as a sustained drip; not a flood.

Do it for your younger self. Do it for your pain and trauma. Do it for your growth.

Share your work.

Your book doesn’t make you an expert. It makes you a student.

Finishing a book is an opportunity to share your work, voice, and ideas with others, yes, but it’s imperative that you listen after it’s published. A lot of people say, ‘don’t read the reviews!’ and while this can be a wise idea, you should listen in from time to time.

What did readers like or dislike? What would have affected them more? What do they see as your strengths? Where did you fail them? What was poorly done? What was beautiful?

Let go of the ego. All of the pictures, attention, and media coverage is temporary. Your job is to be grateful for any positive response you get and then understand how you can grow from there.

People are going to really dislike your book.

I see a lot of bad reviews for lots of books. This may happen to your book too. Some are valid, sure, but others are straight-up ridiculous: “Why wasn’t the book about THIS” or “I don’t agree with the author.” There are just some things you can’t argue with. One book can’t cover every single person’s expectations or experience, so just move on.

Light Magic for Dark Times, so far, has been understood for what it is: An accessible guide to adding ritual and magic to your life, no matter your belief system. The book’s intro explicitly says that it’s not an introduction nor an explanatory guide to witchcraft, but guess what? There have been one or two readers who were peeved that the book wasn’t witchy enough or that it was too accessible.

The thing is, that was my point. And although the ego hurts a little after reading these blows, you have to let it go. Because what’s more important? The fact that you wrote a book or the idea of someone, somewhere, or gravely misunderstood your intention and then went online to complain about it? Thank u, next.

The desire to heal and be understood is universal, no matter what you write.

Maybe you write thrillers or poetry or essays or erotic sci-fi. Whatever. Maybe your work doesn’t center on healing. The thing is, you’re giving something to your readers. Maybe it’s an escape. Maybe it’s a way to find inspiration in another character’s strength. Maybe it’s a way to find solace in grief. When you approach your writing as a gift of love and service to the world, I believe it strengthens it.

I am so grateful that Light Magic for Dark Times has helped people. It’s healed me. It’s created an echo of love that I will never forget and never take for granted. If this has taught me anything, it’s that humans come to books to be seen, to be known, to be transformed. Writing (and reading) has forever been changed for me because of this. And I think that’s an electric, beautiful thing.

You can check out LIGHT MAGIC FOR DARK TIMES right here.

Photo: Joanna C. Valente

When It Feels Like Everyone Is Gone & You Are Alone—But You Aren't

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body) (forthcoming, Madhouse Press, 2019), and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

Falling in Love with Penn Hills

Kailey Tedesco lives in the Lehigh Valley with her husband and many pets. She is the author of She Used to be on a Milk Carton (April Gloaming Publishing), Lizzie, Speak (White Stag Publishing), and These Ghosts of Mine, Siamese (Dancing Girl Press). She is a senior editor for Luna Luna Magazine and a co-curator for Philly's A Witch's Craft reading series. Currently, she teaches courses on literature and writing at Moravian College and Northampton Community College. For further information, please follow @kaileytedesco.

Read MoreOn Every Bed You’ve Ever Rested: Notes On Cancer Season

Emmalea Russo’s books are G (Futurepoem) and Wave Archive (Book*hug). She has been an artist in residence at the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council and the 18th Street Arts Center, and a visiting artist at The Art Academy of Cincinnati and Parsons School of Design. She has shown or presented her work at The Queens Museum, BUSHEL, Poets House, Flying Object, and The Boiler. She is a practicing astrologer and sees clients, writes, and podcasts on astrology and art at The Avant-Galaxy.

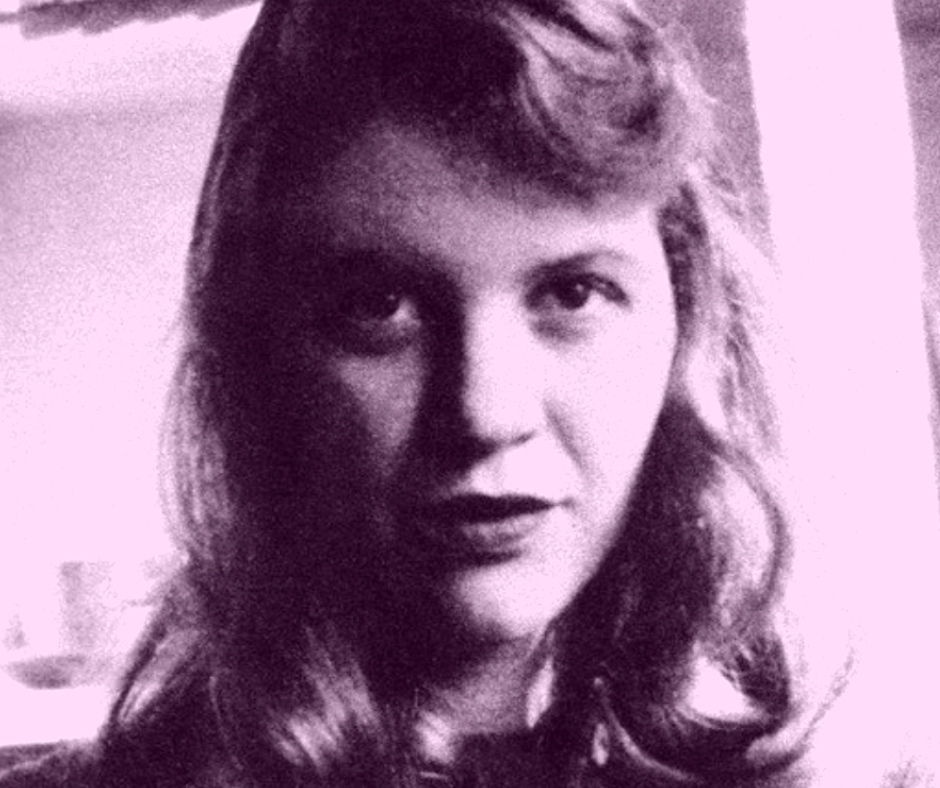

Read MoreWearing Sylvia Plath’s Lipstick

BY PATRICIA GRISAFI

The dutifully hip girl behind the register at the Chelsea Urban Outfitters was sporting a ravishing shade of reddish, hot pinkish lipstick.

“That’s a great color,” I said. “Who makes it?”

“It’s by Revlon. The color is called Cherries in the Snow. You really can’t forget that name, can you?”

I stopped by Duane Reade on the way home and picked up a tube, knowing full well that the lipstick would end up in the heart-shaped box in the closet where all my other lipsticks went to die.

You know how some women wear lipstick every day as a matter of routine? They can apply a perfect lip while riding a bike, walking a tightrope, or herding ten unruly toddlers. I’m not talking about beige-y pinks or fleshy nudes, but serious, bright, punch-you-in-the-face colors.

I’m not one of those women.

Time and time again I’ve proven incompetent at the simple task of applying a lipstick that isn’t the color of my lip; usually, I look like someone’s grandmother in Fort Lauderdale on her fifth Valium and third Mai Tai. Still, every few months, I’ll give a new color a whirl only to frown in the mirror and return to my trusty mess-proof staple since the 90s: Clinique Black Honey.

Would Cherries in the Snow convert me?

I stood in front of the bathroom mirror and carefully drew on a bright, pinkish-red grin. Then I fussed a bit, cleaning up the lines with a Q-tip and some concealer. I cocked my head to the side, bared my teeth like a hyena. I imagined myself tooling around the East Village in white Birkenstocks and large black sunglasses, with a bouquet of bodega peonies in one hand and a coffee in the other. I’d give a breezy, hot pink smile and everyone would think I was quirky and chic.

By the end of the week, Cherries in the Snow was in the heart-shaped graveyard of lipsticks past.

The next time I heard of Cherries in the Snow was in a book. Pain, Parties, and Work by Elizabeth Winder details poet Sylvia Plath’s harrowing experience as a guest editor for Mademoiselle in the summer of 1953. Readers will recognize many of the events Plath writes about in The Bell Jar as based on the details of that summer: getting food poisoning, figuring out fashion, suffering from depression.

There’s one mundane detail that Plath doesn’t include in The Bell Jar: her preferred lipstick: “She wore Revlon’s Cherries in the Snow lipstick on her very full lips,” Winder writers.

I thought I knew an absurd amount about Sylvia Plath. As one of my earliest and long-standing loves, I’ve read and re-read her poems and fiction, written about her work in my Doctoral thesis, visited her homes in both Massachusetts and London, even touched her hair under the careful eyes of the curators at the Lilly Library, Bloomington. But I had missed this small, seemingly insignificant detail.

Revlon has manufactured Cherries in the Snow for the past sixty two years; it’s known as one of their “classic” shades, along with another popular color, Fire and Ice. It’s a cult item, a relic from another era when most women wore lipstick faithfully (a fun but gross tidbit from Winder’s book: one 1950s survey revealed that 98 percent of women wore lipstick; 96 percent of women brushed their teeth). The color isn’t exactly the same as it was when Plath wore it because of changes in industry practice, but it’s pretty damn close.

I scrambled for the heart-shaped lipstick box and sat cross-legged in front of it, fishing around for Cherries in the Snow. I held the shiny black tube in my hand like Indiana Jones held the idol in the beginning scenes of Raiders of the Lost Ark. The lipstick seemed different, changed. Imbued with special meaning. I swiped on a coat, this time imagining how Plath might have applied her makeup, what she might have thought as she looked back in the mirror. Did it change her mood, feel comforting, bestow power?

People are interested in discovering the mundane habits of their favorite singers, actors, writers, and artists. They might even purchase a product based solely on a celebrity endorsement. I’ve always been interested in finding out what products my favorite dead icons used, as if I can access a part of their lost inner lives by slathering on Erno Laszlo’s Phormula 3-9 (one of Marilyn Monroe’s favorite creams) or spritzing myself with Fracas (Edie Sedgwick’s signature scent). Wearing Cherries in the Snow allowed me to experience a strange intimacy with a writer I admired, even more so than reading the very personal things Plath wrote about — including how satisfying scooping a pesky glob of snot from her nose feels.

Ultimately, Cherries in the Snow did not become my lipstick, but I gained an appreciation for the shared ritual with and strange connection to Plath that it allowed me to experience. So many of the artists who have influenced our lives are gone; it feels comforting to find a bit of their essence in something as tangible as makeup.

Patricia Grisafi is a New York City-based freelance writer, editor, and former college professor. She received her PhD in English Literature in 2016. She is currently an Associate Editor at Ravishly. Her work has appeared in Salon, Vice, Bitch, The Rumpus, Bustle, The Establishment, and elsewhere. Her short fiction is published in Tragedy Queens (Clash Books). She is passionate about pit bull rescue, cursed objects, and horror movies.

My Mother, My Origin, Mrs. Leeds & the Jersey Devil

Kailey Tedesco is the author of These Ghosts of Mine, Siamese (Dancing Girl Press) and the forthcoming full-length collection, She Used to be on a Milk Carton (April Gloaming Publications). She is the co-founding editor-in-chief of Rag Queen Periodical and a member of the Poetry Brothel. She received her MFA in creative writing from Arcadia University, and she now teaches literature at several local colleges. Her poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. You can find her work in Prelude, Bellevue Literary Review, Sugar House Review, Poetry Quarterly, Hello Giggles, UltraCulture, and more. For more information, please visit kaileytedesco.com.

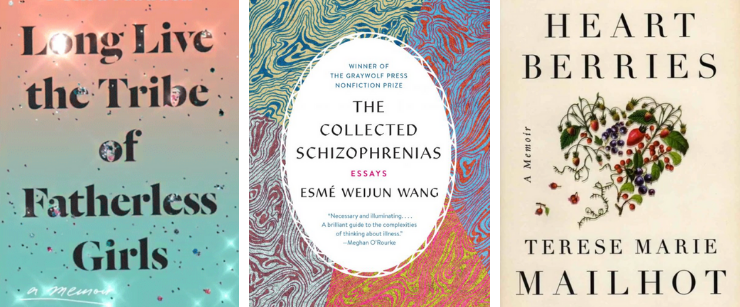

15 Books By Women We're Loving Right Now

BY LYDIA A. CYRUS

Here is a list of books written by brilliant women in non-fiction, poetry, and fiction — inspired by this past Women’s History Month.

User Not Found by Felicity Fenton

This book is actually a tiny essay. Think: A powerful essay about the intricacies of social media and womanhood that fits in your pocket! Fenton writes about her life in social media (and out). If you’ve ever wondered about the color of apps, been sent a dick pic, or just wondered about the profundity of existing digitally in present day, this essay is for you. Fenton wonders at one point if anyone is thinking about her. This thought leads her to the realization that she is, “just a human mammal amongst billions of other human mammals. I’m dander in the corner, the buzz in the background.” Fenton’s lyrical work is biting and honest and I’ve been keeping her little book on my nightstand for those nights when I’m up too late, window shopping on Etsy and checking Twitter every five minutes.

Goodbye, Sweet Girl by Kelly Sundberg

Sundberg’s memoir centers around the physically and mentally abusive relationship with her husband. She chronicles the life of a woman from a working-class background who aims to not only exit an abusive marriage but to also gain an education and return to herself. The memoir is a fast read, lyrical and endearing. Sundberg writes the truths that are hardest to say and quite frankly doesn’t give a damn if the truth reveals the brutality that others have hidden. She reminds the reader all along the wild, highly intelligent woman she was before the abuse never left the room and will always triumph in the end.

Heartberries by Terese Mailhot

Mailhot, a First Nation Canadian writer, weaves together the story of her life revealing the trauma and silence that clouded her. Her memoir welcomes the reader into the scenes of her early life with her mother and leads the reader to the revelation that perforates her story. The truth, she writes, is essential and the most powerful thing to unleash. She writes about her diagnosis of PTSD and bipolar II, the bitterness of loss in relationships, and provides insight into what the pathway to after looks like.

Excavation by Wendy C. Ortiz

When I saw the cover of this memoir, a stunning photo of a young Ortiz at the beach, I felt compelled to look further. Excavation explores the relationship between a young Ortiz and her teacher, a man fifteen years older than her. He fuels her passion for writing and helps her to access a powerful sense of self as a teenager living with her alcoholic parents. Ortiz does the daring task of unraveling preconceived notion of what a predatory relationship is and what a victim looks like. She proves that the world and the relationships we create within it is made up of uncertainty and nothing is what it seems to be.

Boyfriends by Tara Atkinson

Atkinson writes about a young woman whose journey from first boyfriend, to college, to second boyfriend, and beyond. She reminds readers about what it feels like to have your first kiss, first real crush, first everything. And how, as you get older, not only do you change but your desires and wants change too. She explores what it means to be a single woman in 2019, searching in person and online for connection. It’s sweet and nostalgic in the best ways, and will make you think about what it means to be in a relationship not only with others, but with yourself too.

Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls by T Kira Madden

I have patiently awaited the arrival of this book for months. Admiring Madden through my phone screen and awestruck by the glitter on the cover of the book (it’s seriously a beautiful cover). Madden’s memoir takes you to Boca Raton, Florida where, growing up as a queer, biracial teen, her concepts of right and wrong, beauty and ruin live together. Her parents are battling their own addictions and realizations as she tries to navigate the spaces around her. Madden, an acclaimed essayist, wields her language fiercely and writes fluidly, stitching together the warm, sometimes heartbreaking, answer to the question, “what do you want to know?”

Starvation Mode by Elissa Washuta

I picked Washuta’s book My Body is a Book of Rules last summer and loved it so much that I read most of it in the bathtub. Washuta’s prose is so illuminating and honest that it feels like conversation between the reader and a close, trustworthy friend. In Starvation Mode, she writes about her complicated relationship with food. When nothing is in your control, how do you cope? Washuta struggles to create her body in the image of her longing while also experimenting with the genre of creative non-fiction. Both of which creates a work that stands elegantly and surely as an essential read for women who have complicated relationships with their body, their sustenance, and shattering the traditions of appearance.

The Underneath by Melanie Finn

Follow the trail of unsettling memories and the uncanny, as Kay, the protagonist, as she slowly unravels. While trying to reconcile a tumultuous marriage, the heaviness of motherhood, and a traumatic past event, she begins to wonder what really happened to the family that lived in her house before her. Finn’s novel is a true modern day haunting that deals not with ghosts but with the possession of the demands of being a woman. The novel investigates the things that plague Kay as she tries to solve the puzzles of her life.

The Word for Woman is Wilderness by Abi Andrews

If you’ve ever read or watched the countless narratives about men traveling to Alaska to blow up their lives, you’ve probably wondered why it is there are so few narratives of women doing the same. Women seeking out the natural world as a means of personal growth. Andrews does just that in The Word. The protagonist is nineteen year old Erin who leaves the safety of home behind in order to discover. She questions the history of everything from nuclear warfare to birth control. Andrews tackles the old archetype of the adventure always belonging to a man.

Brute by Emily Skaja

The highly anticipated first collection from poet Emily Skaja deals with remains of an ended relationship. Skaja carves survival and redemption into the landscape of what a women grieving looks like. She writes of pain that begins as internal and seeps into a physicality that beckons her to scale and defeat it. The universal truth of what it feels like to be abused and to move on leaks throughout the poems and enchants the reader. Skaja’s book begins with the same Anne Carson epigraph as T Kira Madden’s and positions the reader to prepare themselves for the journey. Skaja twists the plight of hurt into a weapon that strikes out as beauty and has the potential leave readers in both tears and smiles.

The Empathy Exams by Leslie Jamison

This collection of essays considers the possibilities of what it means to care. Is it ever really possible to feel the pain of others? Over the course of several essay, Jamison depicts curious events such as the story of an actor who presents to medical students as someone with symptoms that the students must identify in order to learn. She also writes about the sense of voyeurism the plagues the pain of women in literature. This collection is an essential piece of reading for those still learning how to balance self-love and love for others too. It doesn’t ask, can you pour from empty cup? but instead defines what that cup looks like and what rests within it and why.

Abandon Me by Melissa Febos

Febos’ first memoir Whipsmart detailed her life as a graduate student working as a dominatrix. In Abandon Me she writes about the difficult reality of longing for connection with others. What happens when you drown yourself in another? She visits relationships both romantic and not and the ways in which abandonment can strike and wound at any time, with anyone. As with Whipsmart, Febos isn’t afraid to have conversations about the elements of her life that both built and seemingly destroyed her. She writes about the longing of belonging. Seemingly asking, what does inclusion look like and how do we achieve it?

The Collected Schizophrenias by Esmé Weijun Wang

One of the most talked about books of 2019, Collected, is a collection of essays telling about the life of a woman who suffers from mental illness and a chronic illness. Wang slices open the examination of what her diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder and examines the chaos of coping. She attests to the incredible resiliency that endures recovery and shapes the future of the diagnosed through her own experiences. When it comes to balancing a debilitating reality with the hopes of a promising future, Wang constructs an important conversation not only about mental health but also about the possibilities of life for women whose lives do not fit into one box or even two.

Animals Strike Curious Poses by Elena Passarello

In this collection of essays, Passarello meditates on the fascinating nature of animals and performance. She discussed what it means to be an immortal animal, placed into history by humans and how their fame came to be. Humanity commodifies the bodies animals both living and not and Passarello presents this with careful prose. She is aware of the ways in which humanity must always somehow have the position of authority over others and spares the reader nothing. She goes so far as to highlight the aftermath of the death of Cecil the Lion in 2015 by repeating the notion that the doctor who killed Cecil did not know he had a name at all. This repetition begs the question: Do we have to name an animal, give it celebrity status, and attempt to mythologize in order to respect it?

Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods by Tishani Doshi

In her third collection of poetry, Doshi aims to rebuke the history of silence surrounding women who have survived. She pulls apart identity and trauma in order to create a space in time where silence is no longer synonymous with womanhood. The poems are constructed with careful detail and attention to movement and sound. As the title suggests, women are no longer hidden but are now returning to their lives with power and the capability of anything.

Lydia A. Cyrus is a creative nonfiction writer and poet from Huntington, West Virginia. Her work as been featured in Thoreau's Rooster, Adelaide Literary Magazine, The Albion Review, and Luna Luna. Her essay "We Love You Anyway," was featured in the 2017 anthology Family Don't End with Blood which chronicles the lives of fans and actors from the television show Supernatural.

She lives and works in Huntington where she spends her time being politically active and volunteering. She is a proud Mountain Woman who strives to make positive change in Southern Appalachia. She enjoys the color red and all things Wonder Woman related! You can usually find her walking around the woods and surrounding areas as she strives to find solitude in the natural world. Twitter: @lydiaacyrus

Writing & Publishing Your First Book: Here's What You Should Know

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

Wild Words is an everyday, accessible, friendly series of how-tos around publishing, writing, and creating. It’s a response to the many inbox queries we get around writing (a lot of our readers come here for the literature, and also want to write!). There is no way these entries can be totally comprehensive, but it’s aimed to provide a general overview of any given topic. Feel free to leave questions (and additional advice!) in the comments below or tweet us at @lunalunamag.

Discussions around the publishing industry can feel somewhat elusive, like a secret society to which you’ll never get an invite. And sometimes, even when you’re in the club, you feel invisible. And that’s partially because writers generally keep quiet about their deals, advances, and agents. It may also come down to internalized elitism; some people protect their knowledge as if hoarding it will ensure they stay successful.

I think the more we help one another out, the better the book industry does as a whole. (One piece I really liked about one writer’s book publishing experience is “In Praise of the Starter Book,” by Alex DiFrancesco.

So, here’s what I’ve learned before and during the process of publishing my first nonfiction collection. Know that I offer up this information not as gospel but as my experience, in the hopes of breaking down some of the mystery.

Indie or Commercial publisher? It’s your choice, and yours alone

There are pros and cons to both! People like to say that you don’t have creative liberty with a big press or that small presses won’t support you as much. But these are generalizations. These are also reductive ideas. There are lots of commercial publishers who give authors a great deal of say in the creative design while there are tons of small presses that work their asses off to support their authors and book lists.

I published my first non-fiction on September 11, 2018, although I’d published several books of poetry with indie presses before then. My nonfiction book was published with a global publisher. It was distributed in several countries, and stocked in just about every store you can think of — from a Barnes and Noble in Florida to an indie shop in North Dakota to an esoteric shop in Scotland. Funnily enough, Australia seems to love the book (thanks, Australia!).

The process was entirely different from what I’d experienced in poetry. For one, I was given an advance (which is rare in poetry) and worked with a large team of people — from designers and copy-editors to marketing managers and sales managers. And because the book would have a global release, the publishing process focused heavily on the business elements: There was an expectation to get hundreds of preorders, attain media coverage, and push the book after its release.

I’m so happy that the book has done well; it’s already in its second printing, and I'm working on a follow-up with my publisher. That said, poetry and indie publishing is where my heart is at, and I will never leave it behind. With indie presses, you really get to collaborate at an intimate, beautiful level; plus, there is a different kind of pressure when you don’t have global distribution. It becomes more about the art and less about the numbers. That’s always, always a win.

You don’t need an agent for every book deal

I found out through a good number of friends —and I’m talking about nonfiction here — that they didn’t pitch their books to agents or publishers/editors. In fact, it was their body of already-published work that resonated with the acquiring editor, publisher, or agent, leading them to being contacted about writing a book.

I didn’t have an agent when negotiating my first book. How did it work? I wrote a few articles for Luna Luna that an editor ended up reading and liking. She then reached out to me about writing what would become Light Magic for Dark Times, as she was seeking someone with a dedicated background in the wellness and magic areas. We went back and forth for a few weeks ensuring we were aligned on our visions.

It’s important to note that I had a website with a clear ‘contact me’ page, and that I was running Luna Luna, which is pretty visible in certain niche communities. In short, get out there: Edit a blog others submit to. Or keep a blog for yourself. And create a path of least resistance for opportunities to come your way.

Do your publishing research and read your contract line by line

During the contract process I learned that it’s extremely important to validate whether or not an opportunity is legitimate and fair and transparent. Ask questions, see if anyone you know has worked with the person or the publishing house, and make sure that other books published by the press are ones you’d want to read. Is the press about to go under? How are its sales? Are its other books any good?

My publisher had worked on great books, and my editor was very transparent the whole time. Of course there were some contractual things I wish I could have changed, like escalating royalty amounts (your royalty may change after a certain # of books are sold) or keeping certain rights (and perhaps would have with an agent) but overall my experience was good.

I was able to negotiate my deal myself, and I did a lot of research in order to do this — both through asking people things and using the Internet. I researched advances, royalties, payment schedule, and other details. My advice would be to do your research if you do get a contract, and to consult with an agent if possible — even if it’s not your agent.

In terms of navigating contracts, I recommend reading these pieces of advice: this, this, this, this, this and this.

Getting a literary agent or editor

There’s no hard or fast rule here. You can email an agent or editor when you’re done with your work (most want to see finished work) or even if you don’t have a book ready. Maybe you just want to introduce yourself. Maybe you meet at a literary conference. Maybe you ask friends who have agents to send you contacts. Maybe you cold-tweet an agent or editor and tell them you love their work and that you’re working on a proposal for them. In today’s world, you’re ultra-connected. Take of advantage of that but know your boundaries. And don’t expect responses. (Sorry, but it’s true).

There are a lot of agents out there, just as there are a lot of publishing houses and editors. You’ll find agents soliciting new writers’ work via Twitter, but you’ll also see agencies listing specific calls for types of queries (here’s an example of a literary agency call for submissions.) And here’s a customizable list of literary agents you can reach out to.

You’re going to want to personalize your queries enough to speak to why you’d like to work with that agent or agency. Most agents want to see finished work, along with a synopsis (here’s a checklist for novelists, although much of this applies to any writer).

When it comes to editors, many will only accept agented work, which means you can’t just send them a submission. However, there are plenty of presses that do accept unsolicited or unagented work. Look for independent presses, many of whom are very open.

The most important piece of advice I have is to be respectful and authentic when contacting agents and editors. You need to be able to explain the core root of your work, along with its relevancy, immediately. Show that you know something about the editor or agent; you wouldn’t believe the amount of bland “Please consider my book for publication” emails these people get. Show a little color. Be personable but professional. Why do you love that editor, that agent, or that publishing house? Ultimately, your talent and voice is what gets the deal, but your personality can help you get in the door.

Here’s an examination of the pros and cons of working with an agent.

Do you need an agent for poetry?

I’ve published several books of poetry. All of them have been with small presses or literary organizations. I simply submitted directly, without an agent — and this is the case for 99% of poetry. Poets usually quite simply submit their work directly to a press for publication. For some larger institutions or major presses, this may not be the case, but for any poet who wants to publish a book, there are thousands of great independent presses that will publish you without an agent.

My advice would be to get single poems published first, and then consider submitting your work for book publication. This helps book editors get a sense for who you and what you’ve done, and it lets them know you have an audience. I’m sure there are other poets who have not done it this way, though, and that’s fine, too.

When working with an editor, find a balance between respectful deference & self-advocacy

As a new author, you will find that it's harder to ask for what you want. For one, you might feel as though you have no right to ask for more money, to demand your book's cover color, or to argue against the publisher's title ideas.

In general, the publishing process is a collaborative one — which is something that will prove illuminating. I'm grateful for that collaborative spirit. However, when you are a new writer, you have to learn to read the room a little. This means learning when to defer to the editor, who likely knows the market and the business side of things better than you do, and it means standing up for your vision when appropriate. You know your work, your voice, your market, and your vision. The book is yours. The book is literally your creation.

Use your voice when you have a gut reaction to your publisher's choices. If you hate the cover color or font, make a stand. I cannot understate this more. My book was late to the printer because I refused to sign-off on the cover, which was designed three times.

When we'd finally settled on a general cover, my editors fought for a dark blue cover. In my mind, I saw my book in a light shade, like pink or ivory. Thus began a slightly uncomfortable back-and-forth, but I stood firm, un-moving — all while being respectful. Luckily, my editor went to bat for me in tremendous ways. In the end, I think the book’s color greatly contributed to its success. It stands out amongst a sea of darker covers, and the marbled pink communicates my vision, that the book is friendly, caring, and kind.

Don’t let a book deal change your relationship to writing

The issue with getting a book deal is that you feel somewhat like you’ve reached literary heaven, and in many ways you have. That same passion that you felt about your work can easily be lost to the editing, promotion and the worry-anxiety-imposter syndrome fest that inevitably follows suit. Be mindful to keep your relationship with writing. When I am not, it’s like I train my brain to say "publishing is the end goal," when really, it's about the writing. Writing is always there for you; she is your original home. She is beautiful and generative even when everything else feels still, heavy, or scary.

Imposter syndrome is natural and potentially inevitable

I’ve talked with so many writers about imposter syndrome. This little beast is natural, and there’s almost no way past it but through. You will feel you don’t deserve a book, your voice doesn’t matter, that you cheated someone or something, that no one will like your work, that you’re not nearly as good as your peers, and every little thing in between. The reality is that there’s no solid advice here; you simply must accept that these thoughts are normal, most people have them, and that they will pass. All that said…

Take note of your hard work

You are a writer for a reason. Your passion, your drive, your vision, and your dedication is what brought you to this very point. That’s enough. That’s more than enough. The rest is just politics and bullshit you internalize about yourself and success, and the disease of elitism teaching you that you’re not enough.

I like to create a gratitude board where I pin photos or arrange words that celebrate my successes and projects. (Remember success looks very different for each of us; sometimes it’s finishing a paragraph or a chapter, and sometimes it’s finishing your book).

Be ready to promote your work

This is the best advice I can give you: Be ready to promote your work. I don’t mean post about it once a month on Facebook. I mean make spreadsheets of people you want to reach out, reviewers you’d like your work to be reviewed by, magazines you want to be interviewed by, and stores who might want to stock your book. Even if you work with [insert-fancy-name-press-here], you will be the one generating book sales. Your publishing company can help, yes, but there’s nothing like an author’s touch. Don’t be afraid to promote. It’s literally your job.

Quadruple the output if you’re on an indie press. Yes, this might sound scary — but if you want the book to reach readers, it’s a necessity.

You will lose people when you succeed, but you will gain so much more

In artistic communities, there is always a small percentage of people who let ego and jealousy run rampant. This makes it hard for them to congratulate you, support you, or even recognize you. Sometimes, silence speaks loudly. Don’t be surprised if your peers, colleagues, and even friends act differently toward you.

We’ve all been working toward a goal of being seen and validated; many people aren’t given the opportunity to bloom — whether it be because of a lack of access, a lack of money, a lack of time or childcare, illness, or a lack of drive.

What we can do is continue sending the elevator back down. Continue supporting people by sharing their work. Continue sharing our knowledge. Continue creating a space where other voices can shine. But what we can’t do is change the way people feel about our success. And, you know, it’s not really about you; it’s about them. Take comfort in that.

When you publish your first book, it can leave you with all that imposter syndrome, yes — but it also gives you a dose of confidence, a sense of accomplishment, a new set of skills, and insight as to how this all works. You will likely meet new friends, join new communities, and even be offered new opportunities. Revel in that.

Reader Questions

I asked Luna Luna readers what they’d like me to answer in this column, so here are their questions:

Q: What is one piece of advice that is passed on less of the time that helped you break through to being published?

I think there’s this idea that you need to spend money on expensive residencies, get published only in the big journals (like Tin House, Paris Review) or attend the best MFA programs. I did attend an MFA program, and I can say that while it gave me the credentials to teach, all of my opportunities came from sending my work to indie journals, connecting with writers in digital spaces and at free literary readings, and working hard to hone my craft. With a full-time job, medical bills and other necessities, you do what you can. Do your best work, and don’t let elitist or reductive ideas and opinions get to you. The literati is a small contingent.

There is not one path to publication.

Q: Does it matter if you write into a genre or ideology that happens to be trendy or popular? Like I feel like nonfiction memoirs are coming out all the time now, should we all be writing memoirs? (No shade I read and love them).

Definitely not, but hey — you do you. I know someone who made very good money writing paranormal erotic ebooks when Amazon ebooks were booming. But look, you probably want to write what feels right to you. If it doesn’t feel authentic or natural, the writing probably won’t be very good — and the message won’t resonate. I’m aware that others might disagree, but that’s definitely my stance.

Light Magic for Dark Times came out during a boom in mind/body/spirit titles — and while the genre was trendy, it’s never really been not trendy. People are always interested in self-development and magic and personal power. Not to mention, it gave me a chance to create something new in the genre. I am in love with it.

Q: Where can I find information about publishing?

There are some super helpful resources out there (here, here, here, here, and here, for example), including Facebook groups and Twitter accounts dedicated to opportunities and writers supporting writers. Some of my personal favorites include Entropy’s Where to Submit column and Poets & Writers Magazine.

Lisa Marie Basile is the founder of Luna Luna. She is the author of Light Magic for Dark Times (Quarto, 2018), a modern grimoire of inspired rituals and daily practices. She's also the author of a few poetry collections, including Nympholepsy (Inside the Castle, 2018) and Andalucia. Her work encounters the intersection of ritual and wellness, chronic illness, magic, overcoming trauma, and creativity, and she has written for The New York Times, Narratively, Grimoire Magazine, Sabat Magazine, The Establishment, Refinery 29, Bust, Hello Giggles, and more. Her forthcoming work can be seen in Catapult, the Burn It Down anthology, and Best American Experimental Writing. Lisa Marie earned a Masters degree in Writing from The New School and studied literature and psychology as an undergraduate at Pace University.

Image via Tori Amos

Survival and Truth: How Tori Amos' Under The Pink Changed My Life

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

You don’t need my voice girl, you have your own

We were living in a poor neighborhood on the border of Elizabeth and Newark in New Jersey. I took packed “dollar cabs” to school when it was too cold to walk. We used food stamps at the little mercado downstairs, so I only went when my friends went home and I wouldn’t get caught.

On the third floor, our little apartment had two small bedrooms. Mom slept in the living room, on the couch. My mom was always either at the mall working, or out. She was working hard to overcome an addiction, and no matter how big and beautiful her heart was — the monster was winning. When she was out, I would, like a cat, keep an eye or ear open. Hearing the door knob late at night meant I could finally rest. She was home, and my body could wilt. I could sleep.

My brother and I slept on mattresses on the floor; his room got even less light than my did, so he would sit on the floor playing video games for hours in the dark. I could feel the house’s sadness all the way from my bedroom, but I didn’t have the language to manage it. The translation was lost in the heavy air, so I’d shut my bedroom door and ignore him, seven years younger than me. I’d blast my music and pretend to be somewhere else — in the woods, at the sea, wherever I could be free.

My room was my heaven. There was one long window, and that window looked out at a yard where I could watch a neighbor’s dog lounging or chasing butterflies in the summer. In the smallest of ways, everything felt fine. I could siphon that normalcy and try to press it into my chest like a lantern. I’d light it up when I couldn’t sleep.

A room is a sanctuary, an ecosystem, a confessional.For me, it was a place where I transformed from wound into girl.

Tori Amos happened to me during the summer of 1999. I’m not sure how it happened or who recommended her to me, but when I slipped the little Under the Pink disc into the CD player and sat on my bed, I grew a new organ. I was capable of metabolizing the trauma.

When my mother was out, out, out — wherever she was — or when she was in a screaming match with her violent boyfriend in the next room — I was etching Tori’s lyrics, sometimes over and over, into a little notebook.

I couldn’t possibly have understood all of it, as most of the language was either too adult or too cryptic or simply too Tori, but it spoke directly to the wound in a way that needed no translation or filter.

It was the line, You don’t need my voice girl you have your own, that I distinctly connected with. I wasn’t aware of what feminism really meant, not at all at that age or in that era, but I could feel the surge of electricity that came with being validated by a woman. I was suddenly her little cousin, and Tori was my cool older relative — all jeans and red hair exuding some strange, beautiful warmth. Or maybe she was my stand-in mother. My goddess. It was one of my first glimpses of what it could mean to look up to a woman who was full of space and light and hurt, like me, and who, through some digital osmosis could also heal and love me. Who tapped into the small dark pain and cradled it.

My mother was sick. My grandmother was dying. I had no one else I could turn to, but Tori found me in my bedroom and inhabited the space as nightlight, as cool sheets, as framed photographs of possibility.

Is she still pissing in the river, now?

Another element that struck me: the odd narratives. At this point, I was existing in the height of teen melodrama. A word could mean a million things. A lyric could mean anything I needed it to be. And an album could be the digital imprint of my entire life. I didn’t try to dissect the words, as an adult would. Instead, I fell, backwards into her words; it didn’t matter if I didn’t ‘get it’ or if I had no idea who the fuck the grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia was. I hung onto every word because my life was small and broken and dirty, and Tori gave me everything and more. Continents and ghosts and heartache I wouldn’t experience until I was older.

So, of course I’d borrow a computer at school to Ask Jeeves the Duchess, and I’d print out about 28 pages describing the whole history of her life and death. With my newfound Tori knowledge, I’d walk around the halls at school clutching her lyrics and all the weird shit the Internet said about her work as if they were holy texts. I had the secret. I had a bigness in my pocket. I had possibility and potential and the mouth of the piano whispering into my ears.

Really, as long as I had double-A batteries for my disc-man I could move through my day cushioned.

It was around this time I started writing poetry. I often borrowed themes and topics from Tori’s music, becoming obsessed by her stories of sneaking sexual acts and rebelling against religious morals — getting off, getting off, while they’re all downstairs — or her not-so-cryptic words about God — God sometimes you just don't come through/Do you need a woman to look after you? My poems might have been bad, but they turned my sad, small little bedroom into a palace of courage.

Her bravado and bravery asked me to confront things I’d been afraid to think of. For one — god. Raised in a Catholic family of Sicilian descent, the idea of God and morality and shame was stamped into me since childhood. Even if I wasn’t at church every Sunday, I’d never really heard anyone so thoughtfully critique god. (Pretty soon I’d stumble on Tool’s Aenima, but Tori got to me first).

Also round this time I was making out with bad boys who smelled like cigarettes and pulled fire alarms. I was skipping class to hang out with girls I crushed on. I was *69ing calls in the hopes it was a boy. But talking about sex with any seriousness was not the norm. Tori talked about it from the woman’s perspective, and not just in relation to getting fucked by a guy. Her frankness, especially around masturbation, positioned sensuality as something that wasn’t dirty or bad, but sacred and empowered. Reclaiming, exploratory, rebellious. Hers.

Because I started with Under the Pink, I quickly moved on to Little Earthquakes and found out quickly that she had some powerful words around sexual assault. Yet again I was able to confront the massive, festering wound that I’d been carrying around since pre-adolescence, when I was assaulted (repeatedly) by a man in his 40s.

For me, Tori Amos allowed me to inhabit myself. And myself was a place which was always kept burdened by realities far too heavy for what a teenage girl should have to carry.

Tori, for me, was like an early archetype of Hecate, my goddess of night, of ghosts, bringing me into realms where I could confront the dark. She lit the way through my journey.

The strangeness and complexity of her music, the choir girl influence, the jarring juxtapositions, her softness of anger and brightness of disappointment — it was a new language. Between those first and last tracks, an angel’s wings unfurled, alighting a bleak space.

She taught me that words — stories, poems, or lyrics — could be nuanced and odd and nonlinear, rooted in magic and not saturated in a sugary shell for easy consumption.

But most of all Under the Pink taught me that in self-truth, no matter how messy or imperfect or grandiose or weird, a whole spectrum of color could unfold. There I was in yellow, in blue, in lilac. I experienced a shadow life in color. There I was stepping out of my own dark, even for a few moments.

You don’t need my voice girl, you have your own, she said. And I believed it.

Lisa Marie Basile is the founding creative director of Luna Luna Magazine—a digital diary of literature, magical living and idea. She is the author of "Light Magic for Dark Times," a modern collection of inspired rituals and daily practices. She's also the author of a few poetry collections, including 2018's "Nympholepsy."

Her work encounters the intersection of ritual, wellness, chronic illness, overcoming trauma, and creativity, and she has written for The New York Times, Narratively, Sabat Magazine, Healthline, The Establishment, Refinery 29, Bust, Hello Giggles, and more. Her work can be seen in Best Small Fictions, Best American Experimental Writing, and several other anthologies. Lisa Marie earned a Masters degree in Writing from The New School and studied literature and psychology as an undergraduate at Pace University.

Reclaiming Your Holidays After Trauma, Grief, or Change

Find a way to both honor your feelings and let them sit in validity while also making space for adaptability, self-love, and healing through pain.

Read MorePhoto: Joanna C. Valente

The Complexities on Performance and Passing

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, & Xenos, No(body) (forthcoming, Madhouse Press, 2019) and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes, Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente

Non Fiction by Christopher Iacono

"Energia," the fourth song from Battiato’s 1972 debut album Fetus begins not with music but with Italian children either learning to speak or speaking.

Read More